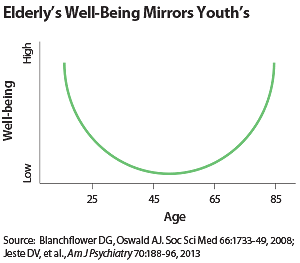

My presidential theme for the past year has been “Pursuing Wellness Across the Lifespan.” How does well-being change across the life-span? The usual notion is that quality of life is high during the first half of life, and then, starting at midlife, it follows a progressively downhill course. Surprisingly, however, a number of recent studies across the world have demonstrated a U-shaped curve of psychological well-being and happiness from age 18 through 85 (see graph). Subjective feeling of well-being is high at the beginning of our adult life, then diminishes progressively until it hits rock bottom in middle age, producing the so-called midlife crisis, but then starts to rise again. Astonishingly, the level of happiness in the early 80s is similar to that in the early 20s.

The increase in happiness after age 50 occurs even as physical health, cognitive function, and fertility decline. Notably, perfect physical health is neither necessary nor sufficient to feel happy as we grow older. Our recent community-based study showed a paradox of aging: physical health and some aspects of cognitive function (for example, working memory) decline with age, while happiness, mental health, and interpersonal relationships improve.

What are the possible explanations for this U-shaped curve? The midlife crisis is typically attributed to factors such as the stress of being a sandwich generation, having the dual responsibility of caring for young children as well as aging parents. Other factors include beginning concerns about retirement, physical illnesses, and mortality, along with a disappointing realization of one’s failed ambitions. People respond to this phase in different ways that are believed to lead to greater happiness after age 50—some change their jobs and/or partners and/or relocate, while others change their attitudes. The latter include a greater acceptance of one’s physical limitations, contentedness with past accomplishments, reduced preoccupation with peer pressure, and a more realistic appraisal of one’s strengths and limitations.

There are also other positive changes with aging. Older employees tend to be hard working, conscientious, reliable, and collegial, and they take fewer sick days off than their younger counterparts. Studies show that, compared with youth, older adults make better decisions that require experience, are emotionally more stable, and become less-impulsive risk takers. An excellent example is Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who gained international acclaim when he, at age 58, successfully landed U.S. Airways Flight 1549 in the Hudson River after both its engines had failed and saved the lives of all 155 passengers on board. He credited his performance in the face of a looming disaster to age-related wisdom. “It might be that for many years I’ve been making small, regular deposits in my bank of experience, education, and training. And on January 15, 2009, the balance was sufficient so that I could make a very large withdrawal,” Sullenberger said in an interview.

Intriguingly, a recent study found evidence that a U-shaped pattern of well-being was present even in chimpanzees and orangutans, based on the reports by these great apes’ individual caretakers in zoos and other protected areas. Thus, better well-being in older age might be rooted, in part, on biological changes in the brain. This theory is indirectly supported by recent neuroscience research demonstrating neuroplasticity of aging. New synapses, and in some regions, even new neurons, can form in older brains if there is optimal physical and psychosocial stimulation.

Age-related well-being is also associated with other positive personality traits such as resilience, optimism, and social engagement. These traits are partly inherited, but also can be enhanced through behavior and environment. Research has demonstrated that optimistic, resilient, and socially engaged people live longer, happier lives, with lower risk of developing heart disease, depression, and dementia, compared with people who have lower levels of those traits. Positive traits probably serve to counteract the negative effects of various stresses on successful aging.

Old age is not necessarily the age for retirement from cognitive, social, and physical activities—and certainly not from life—but can be a time for new careers and new ventures. There is a variety of role models of successfully aging individuals. Below are examples of a few well-known physicians.

Some physicians continue their professional life in old age—that is, they do not retire from their work. Aaron Beck, emeritus professor of psychiatry at Penn, now in his early 90s, is the father of cognitive-behavioral therapy and winner of the 2006 Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. He continues to write and conduct research. He recently published a new book with his daughter and was an amazingly engaging speaker at APA’s 2012 annual meeting.

Some physicians continue their clinical work. Michael DeBakey, a pioneering heart surgeon, performed more than 60,000 heart surgeries before putting down his scalpel—at age 90. He said that his secret to successful aging was constant intellectual challenge, good salads, and four to five hours of sleep at night.

Other physicians turn to community service. Shigeaki Hinohara, a centenarian, chairs the Board of Trustees of an international hospital and a nursing school in Tokyo. He has published several books since his 75th birthday, including Living Long, Living Good, which has sold over a million copies. He founded the New Elderly Movement and does voluntary work seven days a week.

Finally, there are inspiring examples of individuals who fought physical and mental illnesses and increased their creativity in later life. William Carlos Williams was a pediatrician from Rutherford, N.J., who loved to write poetry. He suffered from major depression and later developed recurrent strokes that led to his retirement. Williams dedicated his remaining years to writing poetry. He wrote his most mature, evocative poetry after retirement, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and Gold Medal for Poetry.

Data on well-being across the lifespan in people with serious mental illnesses are very limited. However, several longitudinal investigations, including ours, show that among community-dwelling persons with chronic schizophrenia, mental health improves in later life, provided they receive appropriate health care and psychosocial support. While survivor bias (that is, the sickest people die young and don’t make it into old age) is a partial explanation, it certainly is not the whole story.

In summary, while aging of body tissues is inevitable, mental deterioration is not. A positive attitude, a rational mix of optimism and realism, resilience, engagement in stimulating physical, cognitive, and social activities—along with a dose of good luck biologically—that is the prescription for successful aging after 50. A glass of pinot noir is optional! ■