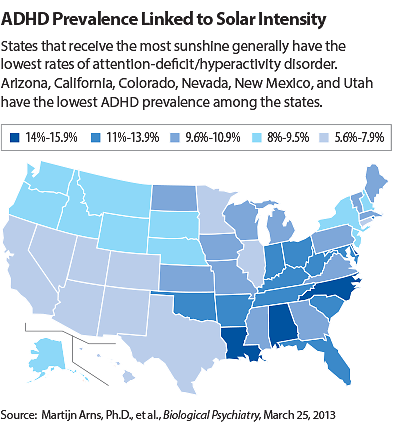

What do Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah have in common? Two things: the greatest solar intensity as well as the lowest prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the country. And there is a significant link between the two, a new study headed by Martijn Arns, Ph.D., director of the Research Institute Brainclinics at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and reported March 25 in Biological Psychiatry has shown.

Arns and his colleagues used both American and international databases on solar intensity and on ADHD prevalence to see whether they could find an association between solar intensity and ADHD. The American ADHD prevalence rates, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, included data from some 73,000 subjects. The international ADHD prevalence rates, which were taken from Belgium, Colombia, France, Germany, Italy, Lebanon, Mexico, Spain, and the Netherlands, included about 11,000 subjects.

Even after controlling for variables such as socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, health care availability, latitude, and altitude, they found a significant association between solar intensity and ADHD prevalence. The greater the solar intensity, the lower the ADHD prevalence. And even after they removed the six states with the greatest solar intensity and the lowest ADHD prevalence—the states mentioned above—the link between solar intensity and low ADHD prevalence was weakened, but nonetheless remained significant.

Thus it appears that solar intensity might have a preventive effect on ADHD, the researchers concluded.

And if so, then sunlight might exert such effects by altering the circadian rhythms of individuals genetically predisposed to ADHD, the researchers proposed.

Discoveries by other researchers bolster this proposition, they said. For example, circadian rhythms appear to be disturbed in 80 percent of adults with ADHD and in 33 percent of children with ADHD. In addition, early-morning bright-light therapy has been found to lessen ADHD symptoms.

The researchers go so far as to suggest that youngsters’ extensive use of modern media such as cell phones and various types of computers might play a role in sunlight’s ability to prevent ADHD.

They explained this hypothesis by noting that use of such electronic devices by youngsters shortly before bedtime has been found to delay sleep onset, shorten sleep duration, and suppress melatonin. And the light intensity of these devices has increased substantially during the past decade, and this emitted light has been found to affect visual processes that directly project to the suprachiasmatic nuclei—the circadian pacemaker in the brain.

Therefore evening use of such devices might suppress melatonin levels, delay the circadian phase, delay sleep onset, and reduce sleep duration, ultimately leading to development of ADHD symptoms in genetically susceptible children. And if this is the case, then intense natural light during the morning might be able to counteract these effects and prevent ADHD.

“The results are certainly intriguing, and if replicated, could help further our understanding of the etiology, treatment, and prevention of ADHD,” David Fassler, M.D., said during an interview. In addition to being a child and adolescent psychiatrist, Fassler is a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont and is treasurer of APA.

Meanwhile, Arns and his colleagues are attempting to obtain further insights into the association between sunlight and ADHD, Arns told Psychiatric News. For example, one of his colleagues is conducting a study investigating the use of light therapy in ADHD. He and his team have a research plan, called the SOLAR-A Project, ready to go, in which they intend to change the lighting inside one or more schools and see whether doing so can reduce ADHD symptoms in children with the disorder.

The study had no outside funding.