A large-scale study based on Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) data disputes the restrictions the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) placed on the maximum dosage of citalopram and its warning on the drug’s cardiac risks.

In 2011 and 2012, the FDA issued warnings that citalopram can cause dose-dependent QT interval prolongation and should not be prescribed for a daily dose higher than 40 mg. For patients over age 60 or with liver-function impairment, the maximum daily dose should be 20 mg, the agency emphasized.

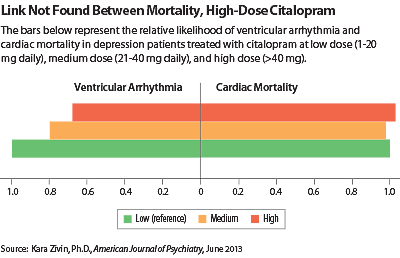

In a study published in the June American Journal of Psychiatry, Kara Zivin, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan and a research investigator with the VA, and colleagues collected data on 618,450 patients who had a diagnosis of depressive disorder and had received a prescription for citalopram from 2004 to 2009. They compared the rates of ventricular arrhythmia, cardiac death, noncardiac death, and all-cause death in those who received high (>40 mg daily), medium (21 mg-40 mg daily), and low doses of the antidepressant (1 mg-20 mg daily).

Patients on high-dose citalopram had statistically significantly lower risks of ventricular arrhythmia, all-cause death, and noncardiac death than patients on low-dose citalopram after adjusting for demographic and clinical factors that could affect mortality (see chart). The risk of cardiac death was not different between high-dose and low-dose citalopram patients.

“These findings raise questions regarding the continued merit of the FDA warning and…whether the warning itself will cause more harm than good,” the authors said. They pointed out that the FDA has not been able to prove the causation between QT prolongation and torsade de pointes. They also noted that citalopram has been available in generic form since 2004, and limiting the dosage in which it can be prescribed has implications for the costs borne by payers.

The authors also looked at more than 350,000 patients who took sertraline, an SSRI that does not carry an FDA warning for QT prolongation or torsade de pointes. As was the case with citalopram, high-dose sertraline (>100 mg daily) was associated with significantly lower risk of ventricular arrhythmia compared with low-dose sertraline (1 mg-50 mg). Cardiac, noncardiac, and all-cause mortality risks had no dose-dependent relationship.

The study was funded by grants from the VA.

The FDA based its citalopram warnings on postmarketing reports of QT prolongation in patients taking the medication and an unpublished study in 119 volunteers that showed an 8.5-millisecond and 18.5-millisecond increase in QT interval associated with daily citalopram doses of 20 mg and 60 mg, respectively. The agency also analyzed a QT study on escitalopram, an S-isomer of citalopram, and concluded that no dose restriction was needed for the isomer, because the QT prolongations associated with 10 mg and 30 mg escitalopram (4.5 and 10.7 milliseconds) were smaller than those associated with 20 mg and 60 mg citalopram.