The true risk factors for suicide among members of the U.S. Armed Forces appear to be mental illness, heavy drinking, and male gender, but not repeated, extended deployments over the last decade to Iraq and Afghanistan.

“[R]isk factors associated with suicide in this military population are consistent with civilian populations, including male sex and mental disorders,” concluded Cynthia LeardMann, M.P.H., of the Department of Deployment Health Research at Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, and colleagues in the August 7 JAMA.

The results challenge much conventional thinking about war, stress, and mental health.

“All are under stress, but only some develop mental illness, and they are at risk for suicide,” said Charles Engel, M.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

“This issue may be broader than deployment or combat,” Engel told Psychiatric News. “After 12 years of war, it may be that the overall strain on the military system has made it a less-supportive culture for soldiers.”

LeardMann and colleagues surveyed respondents as part of the Millenium Cohort Study, a prospective sampling of U.S. troops that began in 2000 and will continue for six decades. An examination of military and civilian death records revealed a total of 83 suicides within the study cohort of 151,560 active and reserve personnel by the end of 2008.

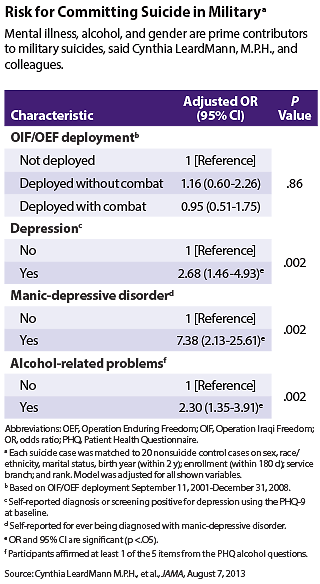

The crude rate of suicide was 11.73 per 100,000 person-years of observation. After multivariate adjustment, only male sex, depression, manic-depressive disorder, and alcohol-related problems remained statistically significant risk factors, said the researchers.

“This suggests that the increased rate of suicide in the military may largely be a product of an increased prevalence of mental disorders in this population, possibly resulting from indirect cumulative occupational stresses across both deployed and home-station environments over years of war,” said the authors.

A separate study found a parallel rise in the number of troops hospitalized for mental disorders, suggesting some support for LeardMann’s conclusions.

From 2000 to 2012, 159,107 active-component service members experienced 192,317 mental disorder hospitalizations, which is a risk factor for suicide, according to U.S. Air Force Col. Patrick Monahan and colleagues writing in the July Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, published by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The annual number of psychiatric hospitalizations rose from 11,604 in 2000 to 21,360 in 2012.

From 2006 to 2012, the increase was largely attributable to increases in hospitalizations for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (192 percent), depression (66 percent), alcohol abuse and dependence (110 percent), and adjustment disorder (52 percent).

The deployment history of those hospitalized varied by diagnosis. About 80 percent of those with adjustment disorder had never deployed, compared with 22 percent of those with PTSD.

“[K]nowing the psychiatric history, screening for mental and substance use disorders, and early recognition of associated suicidal behaviors combined with high-quality treatment are likely to provide the best potential for mitigating suicide risk,” suggested LeardMann.

However, suicide prevention has proved to be a difficult task for Pentagon health officials.

“Soldiers don’t like the current treatment model, with separate mental health service sites, where their presence reveals the category of their diagnosis,” said retired Army psychiatrist Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, M.D., M.P.H., chief medical officer of the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health, in an interview. “People are more likely to prefer primary care.”

Engel goes a step further.

“[L]asting military success in the identification and treatment of mental illness antecedents of suicide will require overcoming current overreliance on outdated combat and operational stress models of suicide prevention,” he said in an editorial accompanying LearnMann’s article in JAMA.

“These findings offer some potentially reassuring ways forward,” he noted. “The major modifiable mental health antecedents of military suicide—mood disorders and alcohol misuse—are mental disorders for which effective treatments exist.”

In recent years, Engel and his colleagues have developed and implemented at 90 military primary care clinics a program called RESPECT-Mil. In the program, troops are screened for PTSD and depression, and soon will be for alcohol problems as well. “We give the primary care doctors the tools to screen, treat, and refer,” he said.

“A lot of work has been done, and there’s a lot of work still to be done,” he told Psychiatric News. “Nonmedical generals are talking about mental illness now. That’s a revolution in itself. There’s recognition of the importance of the mental health service system and a move toward evidence-based ways of providing mental health care. Now we need to follow up.” ■