It is known that individuals with autism are born with a normal head size, but that head growth accelerates compared with typically developing children, sometime during the first year of life.

Thus, it is possible that if excessive head growth during the first year of life characterizes autism, then excessive cerebral volume growth during the first year might do so as well. And indeed a prospective study published online July 9 in Brain suggests that this is the case.

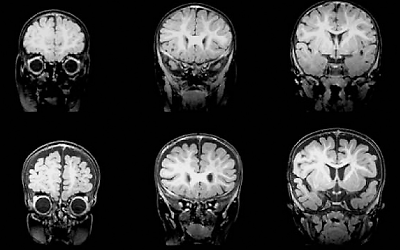

The senior scientist was David Amaral, Ph.D., chair and research director of the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis. The study included 55 infants—33 at high genetic risk for autism because they had an older sibling with autism and 22 not at high genetic risk. Amaral and his colleagues used MRI imaging to visualize the brains of all of these infants between ages 6 months and 9 months.

The brains of 43 of the 55 infants (27 at high risk and 16 at low risk) were also imaged between ages 12 months and 15 months, and the brains of 42 of the infants (26 high risk and 16 low risk) were imaged between ages 18 months and 24 months.

All of the infants were also evaluated for factors related to cognition, socialization, communication, and motor functioning. By age 24 months or later—on average at 33 months—10 of the infants (all high risk) met DSM-IV criteria for autism. Amaral and his colleagues then assessed whether there had been, between ages 6 months and 24 months, brain anomalies in infants later diagnosed with autism.

They found that such anomalies did appear. Compared with the other infants, those who were later diagnosed with autism had significantly more cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space, particularly over the frontal lobes between ages 6 months and 9 months, which persisted and remained elevated at 12 months to 15 months and still at 18 months to 24 months.

In addition, infants who developed autism had significantly larger total cerebral volumes at both the 12- to 15-month evaluation and at the 18- to 24-month evaluation. And perhaps most strikingly, there was a high correlation between the amount of cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space at ages 6 to 9 months and the severity of autism symptoms at 24 months—the more fluid, the more severe the symptoms.

Thus, an abnormally large head, as well as an abnormally large brain volume, and particularly a surplus of cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space over the frontal lobes, may be defining characteristics of autism during the first year of life.

If that is the case, then these anomalies might be used to help diagnose autism as early as age 6 months, the researchers believe. Diagnosis currently takes place on average at age 4, according to 2012 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Seeing a child younger than 12 months of age with an abnormally rapidly growing head (particularly a sibling of a child with autism spectrum disorder) is a reasonable signal for an early MRI evaluation,” Amaral said in an interview with Psychiatric News. “The presence of increased [cerebrospinal] fluid would [then] be a warning sign that the child should be closely monitored for behavioral signs of autism spectrum disorder,” and if the child showed such signs, then intensive behavioral therapy could be implemented earlier than is often the case.

“We are following up this study in a variety of ways,” Amaral said. “Perhaps most fortuitous is that we are collaborating with Dr. Joe Piven at the University of North Carolina, who is the principal investigator of a multisite study called the Infant Brain Imaging Study. This is also an infant-sibling study, but the population of children studied is much larger than in our study. We hope to determine whether our finding is replicable within the next year.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. ■