First lung cancer, then heart disease. Now mental illness may prove to be another baleful outcome of smoking cigarettes.

Two Johns Hopkins researchers said their findings add a new statistical twist to prior research and help “point to an increased smoking-attributable burden of mental health morbidity and impairment in functioning.”

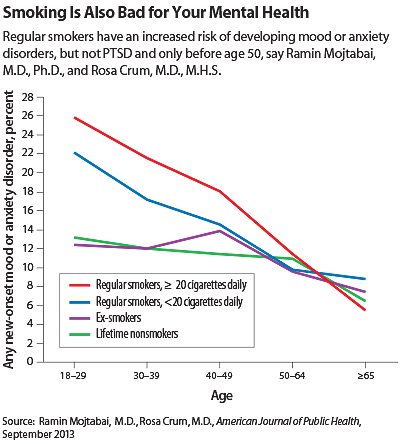

The use of tobacco is usually seen as a form of self-medication in people with mental illness, but perhaps the flow of causation also runs in the opposite direction as well, said Ramin Mojtabai, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of mental health, and Rosa Crum, M.D., M.H.S., a professor of epidemiology and of mental health, both at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in the September American Journal of Public Health.

The researchers based their study on data from wave 1 (2001-2002) and wave 2 (2004-2005) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The 33,154 participants were divided into current regular smokers (18 percent), nonsmokers (54 percent), and ex-smokers (28 percent).

The current smokers, especially those lighting up at least a pack a day, were two to three times more likely than the nonsmokers to meet lifetime criteria for mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders.

After adjustment for a number of sociodemographic and psychiatric factors, they found “a statistically significant association between regular smoking and new onset of any mood or anxiety disorder as well as specific disorders, except for generalized anxiety disorder.”

However, that association held true only for participants under age 50. Among older smokers, only new-onset manic episodes were associated with smoking.

Why younger age had an effect on outcomes was not clear, said Mojtabai and Crum. They speculated that there might be a “risk window” for mood and anxiety disorders among younger participants, or perhaps smokers with mood and anxiety disorders may die younger. Alternatively, there might be some hypothetical protective effect of hormonal changes associated with age. Future research could shed light on these possible explanations, they said.

Another exception to the general pattern was posttraumatic stress disorder, in which the difference between smokers and nonsmokers was not significant.

The researchers said aspects of the results argued for more than a simple association.

Because regular smokers without mental disorders at baseline recorded a higher incidence of disorders at three years of follow-up, the temporal order of smoking and mental disorders support a causal relationship, said Mojtabai, in an interview. So did the dose-response relationship.

“We found that the association was generally stronger for those who smoked a larger number of cigarettes, and stronger for current smokers than ex-smokers,” he said.

Biological mechanisms to explain how smoking might induce mental illness were also speculative, they said, noting one hypothesis suggesting that that “chronic administration of cholinergic agents may lead to indirect inhibition of the nicotinic receptors (functional antagonism) and hence contribute to the prevalence of depression.”

Their work provides still more evidence of the need for antismoking efforts, especially those directed at young people, they concluded. Increased public-health education about smoking and its effects, coupled with higher cigarette taxes, could help reduce smoking and save a few more hearts, lungs, and minds.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. ■