Saving money is one of the big selling points for mental health courts, but a six-year study finds that participants in mental health courts cost an average of $4,000 a year more than a matched group of jail detainees who received jail-based psychiatric services. The additional costs were due to the treatment received through the mental health court system and were not offset by criminal justice cost savings.

“The findings presented here call into question some of the assumptions of mental health court advocates who argue that participation in these courts will result in more cost-effective and efficient interventions for jail detainees who have a serious mental illness,” concluded Henry Steadman, Ph.D., of Policy Research Associates in Delmar, N.Y., in the September Psychiatric Services.

“There may be cost shifting, but there may not be cost savings,” added Steadman in an interview with Psychiatric News.

However, the increase in costs may not be a bad thing, said APA President-elect Reneé Binder, M.D., a professor and director of the Psychiatry and the Law Program at the University of California, San Francisco.

“That reflects increased mental health care utilization, especially for people with co-occurring substance abuse disorders and a criminal history,” Binder told Psychiatric News. Prior research (including Binder’s) has showed that mental health court participation decreases recidivism, jail days, new arrests, and violence. “So beyond the cost issue, the outcomes of mental health courts are valuable for public safety. It’s a good thing from the patient’s point of view and from a public-safety point of view.”

Mental health courts are a type of voluntary diversion program that allows some people with mental illness facing criminal charges to accept court-monitored, community-based treatment instead of going to trial or jail.

Steadman and colleagues tracked 296 mental health court participants and 386 matched jail detainees for three years prior to a target arrest and then followed them for three years after that point.

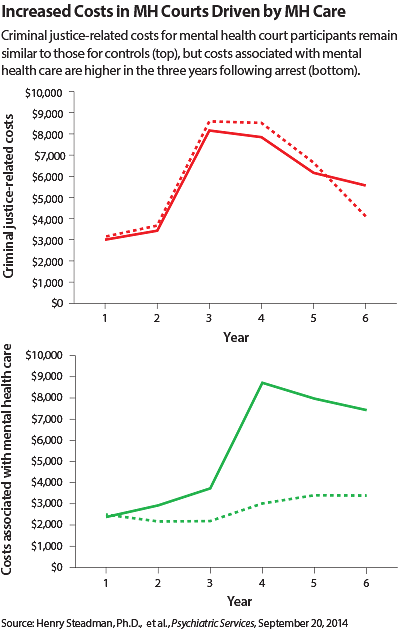

Both total and criminal justice costs for both groups rose in the three years prior to the arrest, with 86 percent of the average criminal justice costs coming in the year just before the arrest.

Findings Contradict Earlier Study

One of Steadman’s earlier studies found an increase in costs in the first 18 months after entry into a mental health court program (reflecting an acute need at the start for housing, employment, and other services, as well as treatment) followed by declines. But that’s not what happened in this study, which covered a longer time period.

In the current study, the mental health court participants incurred an average of about $4,000 annually in additional total charges over the three years following their arrest.

“We were very surprised,” said Steadman. “We thought we’d get the same pattern.”

The difference was attributable to higher treatment costs: $6,000 more than the control group in year 4, $5,000 in year 5, and $4,500 in year 6, said Steadman and colleagues. These higher costs were not offset by criminal justice costs, which were slightly lower in years 4 and 5 but higher in year 6.

Participants with a co-occurring substance abuse disorder and those who spent more time in jail following arrest were the costliest to care for, they said.

The results may seem counterintuitive: if offenders stay out of jail and in treatment, they should incur fewer costs.

“I think you do get reduced criminal justice involvement, but the people who get enrolled in mental health courts don’t need just short-term treatment around some high-acuity issues,” he suggested. “They’re going to need long-term intensive services.”

Better Evaluation of Candidates Urged

Courts must do a better job of knowing what services are available in the community and then matching offenders to them, he said. If evidence-based services are not available, then perhaps offenders should not be enrolled in mental health court programs.

“Or maybe the court has to stimulate development of those services in the community,” he said.

A second study in the same issue of Psychiatric Services compared 198 criminal offenders with mental illness enrolled in a mental health court program with a similar number who were processed through the usual criminal court system in Florida.

“Mental health court assignment predicted a lower overall rate of recidivism and longer time to rearrest for a new charge compared with assignment to traditional court,” wrote Joye Anestis, Ph.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychology at the University of Southern Mississippi, and Joyce Carbonell, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Florida State University.

They noted that increased attention and supervision provided by the mental health court process are probably not the mechanism of action that explains the differences between the two cohorts.

“One might conclude from both studies that spending more on mental health treatment for these individuals is a nonessential luxury when the court intervention itself seems to reduce recidivism with no measurable mental health benefit,” said Marvin Swartz, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, in an accompanying commentary. “Such conclusions would be vastly premature.”

In fact, longer studies of mental health courts are needed to “assess the mental health functioning of court attendees, the appropriateness of the treatment they receive, and the extent to which the treatment comports with evidence-based models,” wrote Swartz. ■

An abstract of “Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health Care Costs of Mental Health Court Participants: A Six-Year Study” can be accessed

here. Swartz’s commentary, “How Do Mental Health Courts Work?,” is available

here.