In 2011, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA)—the trade association representing major drug manufacturers—reported that 240 drugs intended to treat psychiatric disorders were in development, compared with more than 3,000 for cancer and 750 for infectious disease. A study published in September in Psychiatric Services in Advance may provide some explanations as to why the pipeline for psychotropic medicines is nearly empty.

Researchers from Brandeis University and Truven Health Analytics led an investigation of the current state of psychotropic drugs in the pipeline and potential barriers that may keep these drugs from reaching distribution in the United States.

“Though current medications help many persons with mental health conditions, existing antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other psychotropic medicines on the market do not work well for all individuals,” said the study’s lead author, Peggy O’Brien, Ph.D., research leader of Behavioral Health and Quality Research at Truven Health Analytics, in an interview with Psychiatric News. Given that studies have shown that many patients do not respond initially to antidepressants and that schizophrenia is treatment refractory in one-fifth to one-third of those affected, O’Brien and colleagues emphasized that the need to develop innovative treatment is obvious.

“We often read that there are hundreds or thousands of drugs in development, when, in fact, very few of those drugs reach the clinic,” O’Brien explained. “This is not to say that companies are not performing innovative and important research. However, it is important to remember that because of the long pathway of drug development, medications currently in the research and development phase, even if they are ultimately FDA-approved, will not enter the market for many years.”

Tiny Fraction Make It to Phase 1

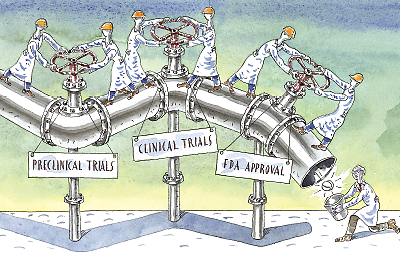

For many pharmacotherapies, the drug-approval process begins with preclinical trials that rely on a series of animal studies. PhRMA reports that for every 5,000 compounds for which companies begin development, only five (0.001 percent) proceed to phase 1 clinical trials, which are conducted with human subjects and overseen by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). During phase 1 through phase 3 clinical studies, the pharmacotherapy is examined for safety, side effects, and effectiveness. Once phase 3 trials are successfully completed, the drug’s sponsor seeks FDA approval for marketing and distribution—which may or may not be granted.

To investigate the current state of psychiatric drugs in the pipeline and why their development is moving at a snail’s pace, O’Brien and colleagues gathered information from academic literature and nonacademic sources—such as industry reports, company press releases, and the National Institutes of Health clinical trials website—on phase 3 trials for drugs being developed to treat major psychiatric disorders, including alcohol use disorder, schizophrenia, and depression. The studies were conducted in the United States as of the final research date of November 14, 2013, and involved adults aged 18 or older.

The analysis showed that the pipeline for psychotropic drug development—99 clinical trials were included—is limited, with little product innovation evident. Most of the examined drugs were a combination of existing of FDA-approved medicines or individually approved medicines that were being tested for new indications or delivery-system approaches (such as an injectable version that is similar to an approved oral form).

Only Three Considered Innovative

Of the drugs being tested, only three differed substantially from existing medications. These included a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor for treatment of depression (amitifadine), a drug targeting glycine receptors to address negative symptoms of schizophrenia (bitopertin), and a nicotinic alpha-7 agonist for adjunctive treatment for cognition in schizophrenia (EVP-6124).

Among the barriers that hindered development of psychotropic drugs were incentives that encourage firms to focus on incremental innovation—such as a new version with fewer associated side effects—rather than taking a risk on radically new molecular approaches, the failure of animal studies to translate well to human trials, and drug-approval thresholds set by the FDA that developers and manufacturers may perceive as too high to attain.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Alan Schatzberg, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and a former APA president, said that the departure by pharmaceutical companies from programs to develop innovative psychotropic medicines could result in serious problems for the field of psychiatry, especially for patients.

“There are a number of initiatives by various organizations to help with this problem, including the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, which is working with companies to provide investigators with compounds that have been shelved, and NIMH’s Research Domain Criteria program, which promotes research on specific [and new] biological targets,” he said. Schatzberg emphasized that it will take a concerted effort on the part of government agencies, industry, as well as APA to advocate for investment in innovative psychiatric drug development. “Silence will not be helpful to our patients,” he stressed.

As for O’Brien, she hopes that the current study will provide psychiatrists and other clinicians with a better understanding of the process of drug development and the potential obstacles that may stand in the way of their having new and more effective medications to prescribe for patients with mental illness. To avoid some of these obstacles, she concluded, clinicians, researchers, and pharmaceutical and health care leaders must work together with policymakers to improve the current regulatory framework guiding the drug-approval process. This could “help promote innovation and increase the availability of safe, effective, and innovative medications for those with behavioral health conditions.” ■

The abstract of “The Diminished Pipeline for Medications to Treat Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders” can be accessed

here.