Social anxiety disorder is emerging as one of the most prevalent mental illnesses in the United States, affecting an estimated 15 million people. While social anxiety disorder can be debilitating, the good news is that many psychological and pharmacological therapies have been shown to work.

However, the big picture of social anxiety interventions remains a bit murky; some studies have reviewed and analyzed existing data, but these meta-analyses generally focus on comparing one approach with another.

Evan Mayo-Wilson, D.Phil., an assistant scientist at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, told Psychiatric News, “When you do a pairwise comparison, you’re not really looking at all the evidence you have available.”

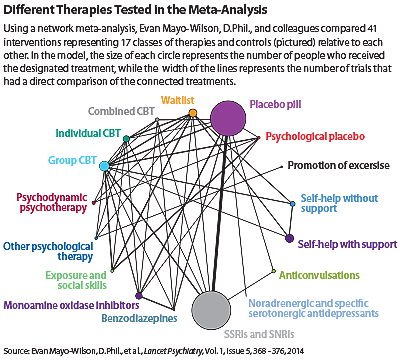

So to get a better understanding of how the disorder is treated, Mayo-Wilson and his colleagues in the United Kingdom (where he worked before going to Johns Hopkins) turned to an emerging methodology—a network meta-analysis, which can compare the effectiveness of multiple treatment options relative to each other and to a common reference.

They combined the results of 101 clinical studies for social anxiety disorder and compared 41 therapies: 15 using drugs, 18 using psychotherapies, five using a combined approaches, and three types of controls.

The findings, which were published in The Lancet Psychiatry, reinforced the wide range of options available to people with social anxiety disorder, as almost every intervention showed some benefit compared with waitlist, a type of control group that effectively means no intervention; exercise promotion, interpersonal therapy, supportive therapy, and mindfulness training were the exceptions.

“A big take-home message from this study would be that we need to improve patient access and ensure that we have enough trained clinicians available,” said Mayo-Williams. “These results show the worst thing you can do to patients is to make them wait.”

Having enough therapists trained in psychotherapy is of particular importance, noted Mayo-Williams, because of all the options his group analyzed, individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) came out on top.

When compared with waitlist, CBT had an overall effect that corresponded to number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of fewer than two. NNT measures how many people need a treatment to benefit one person, so values closer to one are more ideal.

CBT was also one of only two interventions that still showed significant benefits when pharmacological or psychological placebo controls were used as the comparison instead of waitlist. The other effective treatment was selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs/SNRIs).

The investigators noted that since SSRIs/SNRIs can cause side effects, and since people can relapse once they stop taking the medication, CBT should be considered as a first-line treatment option, though they acknowledged that many people with social anxiety disorder may not have a desire for, or access to, CBT. In such cases, they suggested that patients should be given SSRIs if they prefer pharmacological treatment, while a CBT-based self-help therapy with support would be recommended for those who want a psychological intervention.

“We hope that this analysis will start steering therapists away from prescribing suboptimal treatments for social anxiety disorder,” Mayo-Williams said. “The U.K. has done a good job of developing treatment guidelines based off of our group’s research, and we hope the U.S. will follow suit. Psychiatrists and psychologists need to come together to help get this done.”

While this network analysis has provided a more clear hierarchy of treatment effectiveness for social anxiety disorder, Mayo-Williams noted that gaps still remain. For example, the analysis only included five clinical trials that used both pharmacology and psychotherapy, and none of the studies used the same combination, so the possible additive value of combining medicine and talk therapy could not be accurately determined.

This study was funded by England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which develops “public health guidance to help prevent ill health and promote healthier lifestyles.”

“Psychological and Pharmacological Interventions for Social Anxiety Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis” can be accessed

here.