Telepsychiatry and other long-distance options for providing mental health care can help overcome problems related to location and distribution of specialty mental health services but should not be seen as a panacea for delivering care to rural areas in the United States, reported a research and policy brief from the Maine Rural Health Research Center.

“Telemental health” (the authors’ preferred term) once depended on heavy-duty audio and video technology based in fixed studios to initiate care. Advances in computer technology and its near-universal adoption have changed that.

“As technology improves, and its costs decrease, interest continues to grow in using technology to expand access to mental health services to rural residents,” wrote David Lambert, Ph.D., an associate research professor at the center, located in the Cutler Institute for Health and Social Policy at the University of Southern Maine in Portland.

Lambert and colleagues contacted 150 rural telemental health programs and completed surveys with 53 of them about their organizational context, services provided, staffing, and the areas and populations served. They also conducted more-detailed phone interviews with a subset of 23 programs.

About 28 percent of the programs were based at academic medical centers, with smaller percentages scattered among community mental health centers, acute-care hospitals, private vendors, federally qualified health centers, or rural health clinics.

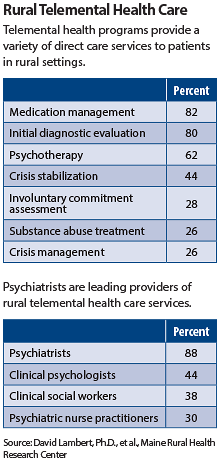

Most of the programs (94 percent) provided direct patient care. About 72 percent offered consultation between providers, and 46 percent used care management or coordination.

Programs make use of a variety of clinicians, wrote Lambert and colleagues. “Telemental health services are most commonly provided by psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, and psychiatric nurse practitioners.”

Respondents expressed concern about the use of private commercial sources of clinical telemental health services. Several reported that it was difficult to maintain service when private contractors end their contracts.

On the other hand, a pilot project begun at one critical-access hospital in collaboration with a psychiatrist and specialty mental health staff at a community mental health center has now expanded to five additional hospitals. This system provides round-the-clock crisis evaluation and support at the hospital emergency departments.

Actual level of use was not clear from the survey. Many smaller programs saw only a few patients per week. Other telemental health programs were mainly used to manage emergencies at remote sites.

“Typically, programs were able to say that telemental health enabled them to provide services to rural persons that otherwise would not be available, but often were not able to indicate with any certainty how much additional volume or new services they might be able to deliver in the future,” the authors reported.

Many programs received some insurance payments for services but also reported that grant funding or other additional support was keeping them afloat.

In fact, nontechnical barriers such as poor Medicaid and commercial reimbursement rates, recruitment and retention difficulties, high numbers of patients without insurance, and high no-show rates serve as a drag on expansion of programs, said the authors.

“The ability of telemental health services to overcome chronic rural behavioral health access issues in the current health care environment is likely to be limited until these fundamental system issues are addressed,” they concluded.