Effective integration of medical and behavioral care could save $26 billion to $48 billion annually in health care costs, according to an analysis by Milliman Inc., an international actuarial firm.

The analysis, commissioned by APA, found that most of the projected reduced spending is associated with facility and emergency room use by individuals with mental health and substance abuse issues. The analysis was contained in the report “Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry.”

Because of fragmented care in the current system, general medical costs for treating people with chronic medical problems, as well as mental disorders, are two to three times higher than those for treating people with physical health conditions only.

The report was released last month at a roundtable discussion in Washington, D.C., titled, “Integrated Primary and Mental Health Care: Reconnecting the Brain and the Body.” The event was hosted by APA and attended by clinicians, thought leaders, and policymakers who have championed collaborative care. A total of 85 representatives from mental health and substance abuse advocacy organizations attended; a live webinar of the event was also accessed at about 300 sites and at press time had been viewed by an additional 300 people.

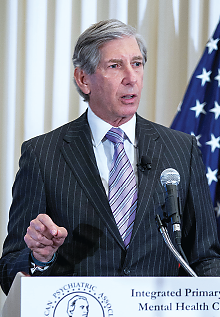

“There is a compelling and growing body of research demonstrating the impact of quality integrated care that treats the brain and the body,” said APA President Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D., in opening remarks at the event. “These studies have shown that concurrently treating behavioral and physical conditions not only leads to better control of depression, diabetes, and heart disease, but has been shown to reduce health care costs. Right now, we treat medical and mental illness as if they occur in different domains, rather than within the same person, but as we all know, there is no health without mental health,” Lieberman said.

Drawing from commercial health insurance and Medicare and Medicaid data, Milliman based its estimates on data from more than 20 million individuals in its analysis of health care utilization and costs from 2009 to 2012. Milliman compared data from four groups: people with no mental health or substance use disorders; people with mental health diagnoses but no serious and persistent mental illness; people with serious and persistent mental illness; and people with substance use diagnoses. Chronic medical conditions in people in each of these four groups were reviewed.

The analysis revealed that only 14 percent of people with insurance are using mental health and substance abuse services, yet they account for more than 30 percent of overall health care spending.

The total U.S. spending for those with behavioral health conditions was estimated to be $525 billion; the additional health care costs incurred by people with behavioral comorbidities were estimated to be $293 billion in 2012, according to the report.

Milliman found that in comparing the health care costs of people with behavioral health conditions to those without, people with behavioral health conditions spend a greater proportion of total medical dollars on facility-based services rather than professional services, such as physician appointments.

The report was commissioned as a result of a report that was submitted last year to the APA Board of Trustees on “The Role of Psychiatrists in Health Care Reform.” It was produced by a work group chaired by APA President-elect Paul Summergrad, M.D. The report, which was released with the Milliman report at the roundtable, covers issues related to the rollout of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but emphasizes that health care reform is broader than the ACA and includes multiple state, federal, and private patient-care delivery and payment initiatives.

The report noted that psychiatrists, because of their medical expertise and extensive training with seriously ill psychiatric and medical patients, have distinctive expertise to integrate this care, working closely with primary care, specialty physicians, and nonphysician mental health clinicians (Psychiatric News, May 3, 2013).

At the roundtable event, Summergrad discussed findings from both reports. He emphasized that integration of mental health and substance abuse treatment and general medical care was crucial to achieving the “triple aim” of health care reform: better patient outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, and lower overall costs. He pointed out that a critical takeaway message from the Milliman analysis is that integrated care of psychiatric disorders is vital to tackling the overall problem of rising health costs.

“We think there is compelling evidence that integrated care of mental health and substance abuse disorders is necessary, not only because of the considerable pain and suffering associated with them, but because there is no way we can really deal with the issues around total health care costs unless we reach out across the mental health and general medical care settings to ensure that we are all working together to provide that care,” Summergrad told attendees.

Michael Hogan, Ph.D., former commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health, noted in this keynote remarks that what he called “disintegrated care” is costly and bad for patients’ health. People wait on average nine years to seek care for a mental health problem, and since the average age of first experiencing mental health problems is 14, these delays come at a particularly bad time in individual development, he said.

“Primary care is slammed by these problems,” Hogan said, noting that behavioral complaints are the number-one reason for pediatric visits and account for approximately a third of family-practice visits. But without integration, primary care is poorly equipped to respond to these issues, Hogan said.

Other panelists included Richard Frank, Ph.D., the Margaret T. Morris Professor of Health Economics at Harvard Medical School; John O’Brien, senior policy advisor for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Michael Schoenbaum, Ph.D., senior advisor for mental health services, epidemiology, and economics at the National Institute of Mental Health; Elinore McCance-Katz, M.D., chief medical officer at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administraton; Frank deGruy, M.D., chair of family medicine at the University of Colorado; Henry Chung, M.D., medical director of the Montefiore Accountable Care Organization and an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine; and Keris Myrick, M.B.A., M.S., Ph.D.c., president of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

In closing remarks, APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A., reiterated that the current system of fragmented care is “costly, ineffective, and bad for health. . . . The Milliman report makes clear that mental health and substance use disorders are too big to ignore,” Levin said.

Levin stressed there is a critical need for reimbursement policies that make these programs sustainable. “And finally we need psychiatrists, working closely with family practice, primary care, and other behavioral health care providers, to help manage patients with complex, comorbid conditions.”

He added, “Together we can help reconnect the brain and body in medicine. The time to do it is now.” ■