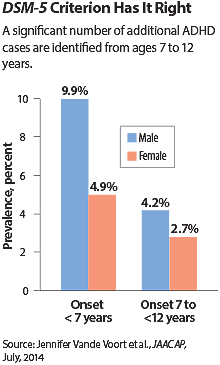

Extending the age-of-onset criterion from age 7 to age 12 increases the 12-month prevalence rate of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from 7.38 percent to 10.84 percent, but that difference may reflect factors other than the disorder itself, according to researchers from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

The age criterion was extended from age 7 in DSM-IV to age 12 in DSM-5.

“Without this extension, nearly 3.5 percent of children who meet all symptom, duration, and impairment criteria for ADHD would go unrecognized,” wrote Jennifer Vande Voort, M.D., and colleagues from the Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch of NIMH, in the July Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

“The study shows what clinicians have known—that children and adolescents who receive a diagnosis of ADHD at age 12 have significant morbidity associated with the disorder and that the clinical impact is no different for those diagnosed at a younger age,” commented Molly McVoy, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at University Hospitals/Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, in an interview.

The researchers drew on retrospective parent-reported data on 1,894 adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Of those, 163 were identified as having later-onset ADHD using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children–IV.

The greatest prevalence increase in the older group occurred in the inattentive subtype, suggesting problems arising at school or reflecting a later developmental stage, said the authors.

In both groups, greater ADHD rates were noted in boys (about 14 percent) than in girls (7.5 percent), but the boys-to-girls ratio was slightly lower in the older group, suggesting improved recognition of the disorder among girls at a later age.

The extended age criterion identified more children from ethnic minority groups and lower-income families.

“In other words, ‘late-onset cases’ are likely simply to be ‘late-recognized cases,’ ” wrote Guilherme Polanczyk, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of São Paulo School of Medicine in Brazil, and Terrie Moffitt, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, in an accompanying editorial. “In this respect, extending the age limit to 12 years may especially benefit children with ADHD from less-advantageous home environments and poorly resourced schools, whose symptoms are recognized later during development, after a longer period of functional impairment.”

Treatment rates also varied between the two cohorts. Later onset among children with the hyperactive/impulsive subtype was associated with a greater likelihood of treatment, compared with their early-onset peers. However, children with later-onset inattentive or combined subtypes were less likely to be in treatment than those with early onset.

Larger, prospective studies are needed to confirm the observations in the current study, said Vande Voort. Nevertheless, the report supports the extension of the age of diagnosis for ADHD to age 12 in DSM-5, said McVoy.

“Once again, the authors show the importance of diagnosis and treatment of ADHD at any age because of the major consequences of the disorder,” she said. ■

An abstract of “Impact of the

DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Age-of-Onset Criterion in the US Adolescent Population” can be accessed

here.