Five university-based divisions of child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP) in New York state are collaborating to provide education and consultation to primary care physicians around issues related to mental health care of their patients.

The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP-PC) initiative, sponsored by a grant from the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), funds the CAP divisions from the University at Buffalo, Columbia University, Hofstra North Shore/LIJ School of Medicine, University of Rochester, and SUNY Upstate Medical University (Syracuse) to provide phone, face-to-face, and telepsychiatric consultation to pediatricians and family physicians caring for children in more than 90 percent of the state.

The five divisions have also partnered with the Resource for Advancing Children’s Health (REACH) Institute—a national organization established in 2006 to develop education for primary care physicians (PCPs) in child mental health—to provide a formal “mini-fellowship” in “Assessment and Management of Child and Adolescent Mental Health.” That mini-fellowship consists of 16 hours over three days of intensive, interactive, hands-on training co-led by child and adolescent psychiatrists and primary care physician “champions” from each of the regional teams. The REACH program covers evidence-based assessment and treatment of several common problems seen in children in primary care offices: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, depression, anxiety, and aggression.

The weekend course is followed by 12 biweekly case-based conference calls for 10 to 12 participating primary care physicians, facilitated by CAP-PC child and adolescent psychiatrists and primary care champions; the biweekly conference calls are a critical chance to apply knowledge from the weekend course to real cases as they appear in a primary care office.

The course provides up to 28 CME credits at no cost to primary care physicians.

David Kaye, M.D., CAP-PC project director at the University at Buffalo, told Psychiatric News that the goal of the collaboration is to assist and support primary care in addressing mild to moderate mental health problems, with an ultimate goal of preventing more serious deterioration. “To have primary care face this squarely and take it into mainstream practice is a welcome step in destigmatizing mental health problems, promoting access to care, and making the kind of strides we need to make in order to assure treatment for all and prevent disability and reduce risk,” Kaye said.

“This is a remarkable and unprecedented collaboration among academic institutions to improve mental health care of children,” he added.

Regarding the REACH training, Kaye said feedback from PCPs who have taken the course has been so positive that the five divisions receiving the state grant have agreed to continue providing the course. “This is not your standard CME course,” he said. “It really is an outstanding educational program that we were all trained and certified in, and we have subsequently provided input and feedback to further develop that program. Because of our grant from the state, we can offer it for free to all PCPs in our coverage area.”

Kaye said two other states—Colorado and Minnesota—have followed New York’s lead and are offering the REACH program in their collaborative care models. “Unlike some collaborative care programs in other states, we have really emphasized the importance of formal education for PCPs as opposed to providing primarily or only phone or face-to-face consultation,” he said. “Our goal is to follow the adage—give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

He is a professor of psychiatry, vice chair for academic affairs, and director of training in child and adolescent psychiatry at the University at Buffalo.

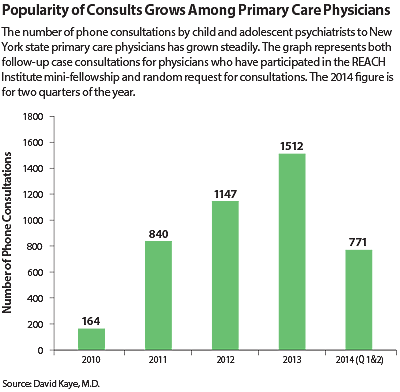

Additionally, the five university divisions have established a single, dedicated, toll-free phone number for any primary care physician in the state to call for consultation on children and adolescent patients with mental health problems. In selected cases, CAP-PC is able to provide a one-time face-to-face or telepsychiatric consultation. From the beginning of the program in late 2010 to the present, 475 New York state primary care physicians have completed the REACH training through CAP-PC; there have been 4,400 phone consultations, including both the scheduled conference calls for participating pediatricians and calls to the toll-free line from clinicians in the field (see chart).

Kaye said the program is funded through the end of this year; he says he is optimistic that there will be a five-year extension in funding from OMH.

The initiative represents a critical element of integrated behavioral health: extending the expertise of psychiatrists and child psychiatrists to primary care and other practitioners.

“We have a terrible crisis of manpower,” child psychiatrist Peter Jensen, M.D., president and CEO of the REACH Institute, told Psychiatric News. “There are about 7,000 child psychiatrists in the country, but the surgeon general has told us there are 14 million kids with mental health and behavioral problems. Families very often don’t want to see a psychiatrist, and most of the problems presenting in primary care don’t need to be seen by a specialist. We need to train primary care clinicians because there will never be enough of us.”

Formerly with NIMH and Columbia University, Jensen said he began organizing training for primary care physicians in mental and behavioral health care in the years following the 9/11 attacks and the 2005 Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans when it became clear that survivors of those events needed comprehensive care that included mental health care. The REACH Institute was formed as a nonprofit in 2006 with projects similar to New York’s CAP-PC initiative in multiple states.

“We are trying to make sure the best interventions for children and adolescents are out there in the field and being used by the people who need them, so we can have a system that really works for kids,” he told Psychiatric News. “We save the difficult cases for specialists in child psychiatry, but three out of four cases in primary care can be managed by the primary care clinician.”

Jensen said the training provided to clinicians in the New York initiative goes well beyond what is offered by traditional CME courses. And training is a crucial—and often missing—link in the movement toward integrated care.

“Many pediatricians are really scared of dealing with mental health and behavioral problems,” he said. “As one recently said to me, ‘Look, I don’t do dental and I don’t do mental.’”

According to a survey of 125 New York state pediatricians who participated in the CAP-PC program in 2013, 92 percent said it increased their knowledge about providing mental health care to their patients, 85 percent said the training increased their skills, and 83 percent said it increased their confidence.

“The New York model is one of the best in the country because it prepares clinicians through the training program and consultation calls, and then those clinicians can become champions of providing mental health care in the primary care setting in their own practices and community,” Jensen said. ■

Information about the REACH Institute can be accessed

here.