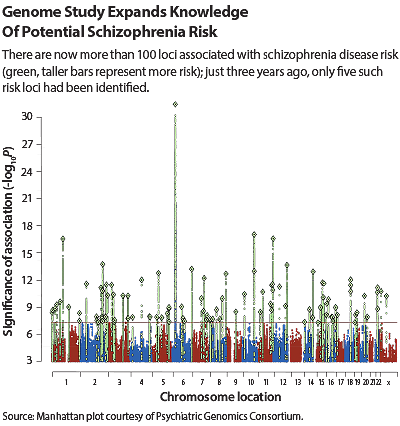

A few years back, there was but a handful of genetic markers that could confidently be linked with schizophrenia risk. But on July 21, Nature published findings from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH)-supported Psychiatric Genomic Consortium (PGC). In an unprecedented effort of collaboration and data sharing, the PGC had pinpointed 108 genetic loci associated with schizophrenia, 83 of which had not been previously identified.

This rapid growth is reminiscent of Dubai, which also transformed from a modest city to a skyscraper-filled metropolis almost overnight. But just as a shiny office tower is only useful if it’s productive, so too these schizophrenia loci need to lead to tangible scientific and clinical benefits down the road.

The immediate thought is whether these loci can be used to predict schizophrenia before it manifests or determine the optimal treatment if it does develop.

“In terms of individual-level prediction, whether a person will or won’t get the disease, we are not there yet,” said Philip Wang, M.D., deputy director of NIMH. “Though we uncovered a large number of genetic variants, they only account for a small percentage of someone’s schizophrenia risk.

“But we are getting to the point where we can begin to act on our genetic findings,” Wang added, noting the PGC study did develop risk profile scores by adding up the various genetic signals and demonstrated that people in the highest category had a 20-fold increased schizophrenia risk.

Having a robust genetic profile will help identify certain subgroups that might be more prone to the disease or to specific schizophrenia phenotype manifestations, but even if hundreds more genetic variants for schizophrenia are uncovered, the complexity and rarity of the disease would make true individual prediction unfeasible, given the near certainty of false positive results.

More potential lies in digging deeper into these associations to uncover potential drug targets. About three-quarters of the loci identified in the PGC study were on or adjacent to a protein-encoding gene, including some well-established players. “Finding a strong association for the D2 dopamine receptor, which is the target of antipsychotics, was particularly reassuring, as it shows that we are dealing with biologically important variants.” said Wang. Additional variants identified in regions relevant to schizophrenia included genes involved in the transport of glutamate—the brain’s major neurotransmitter—and in calcium channels, which regulate how well the connections between neurons strengthen or weaken over time.

Perhaps the most intriguing variations identified were in several genes involved in the immune system, such as for B-cells involved in acquiring pathogen-specific defense mechanisms. “The connection between immunity and mental health has been postulated for decades, but it’s been a puzzle,” said William Eaton, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Mental Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “These genetic findings add more pieces to that puzzle, notably in supporting the importance of adaptive immunity. But, next to the brain, the human immune system is probably the most complex thing on the planet, so we still have many connections to establish.”

Wang agrees with this assessment. “This study has pointed us in several good directions, but it’s just the first installment,” he said. “This coming together of individuals and institutions is happening across the research landscape of mental health, so we will be seeing more variants for schizophrenia and other psychiatric conditions on the horizon. And as we progress, I think we will find more risk factors in the noncoding areas of the genome that regulate gene expression, which will open up even more mechanisms underlying this disease.”

The challenge now is shifting from a research area that has too much information, as opposed to too little. While many of the variants were found in biologically plausible regions, only a handful will end up being integral to disease. Like an old-time prospector, research will have to sift through a great deal of peripheral association to find their nuggets of causation.

Even then the underlying gene, or the protein it makes, may not be a clinical gold mine. “An important thing to remember about this study is that the consortium identified common variants, which by nature have only minor influence on risk,” said William Carpenter, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and former director of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. “It’s possible, but unlikely, that you will find a specific protein that will make a good drug target.”

Instead, researchers should map out known common—and rare—variants to identify pathways and networks where variants cluster. Then, scan those pathways and find proteins that could be the most “druggable,” as opposed to having the strongest risk, he said.

The necessities of drug development will mean that any approved products are still years away, but Carpenter noted that genetic findings might offer more immediate hope for some patients. “There’s a lot of focus on using genetics to find new drugs, but we could also test psychological therapies, which do not require all the regulatory hurdles,” he said. “If we identify defects in a cognition pathway in a patient, for example, we could try cognitive remediation or other behavioral approaches to see if they benefit.”

Even psychological strategies are still likely a ways off, but clinicians, patients, and others affected by schizophrenia should still consider this genetic bonanza a positive step forward. Mental health has been lagging behind other fields when it comes to genetic discoveries, but now it appears ready to join the party. ■

An abstract of “Biological Insights From 108 Schizophrenia-Associated Genetic Loci” can be accessed

here.