The antipsychotic clozapine continues to be dramatically underutilized—despite its being the only drug approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia—and there appears to be significant interstate variation in the numbers of patients in the Medicaid program who are receiving the medication.

That’s the finding from an analysis of Medicaid data in 46 states published November 2 in Psychiatric Services in Advance. Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., of Columbia University and colleagues updated a previous analysis of Medicaid data from 2001 to 2005 to include data from 2006 to 2009.

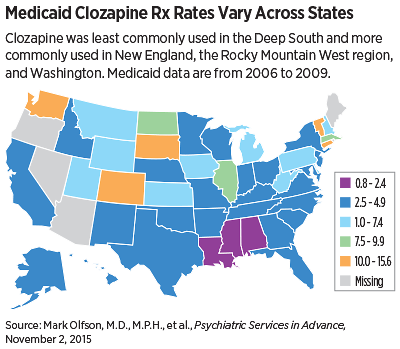

Overall, clozapine accounted for 4.8 percent of antipsychotic use in schizophrenia from 2006 to 2009, with a slight decline during this period (5.7 percent in 2006 to 4.3 percent in 2009). Clozapine was least commonly used in the Deep South (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama) and more commonly used in New England, the Rocky Mountain West, and Washington. The highest rate of clozapine prescribing was in South Dakota (15.6 percent), and the lowest rate was in Louisiana (2.0 percent).

The authors of the analysis noted several factors associated with low clozapine use: fiscal stress, inadequate staffing to monitor clozapine, patient reluctance about blood monitoring, and concerns over tolerability.

According to Deanna Kelly, Pharm.D., of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, only about 5 percent of U.S. patients received a prescription for clozapine last year. “[Clozapine] is underutilized in other countries, but in the United States it is far more underutilized than in Europe and Asia,” Kelly, who was not involved with this analysis, told Psychiatric News. “In Australia, China, and Japan, it is used in upward of 30 percent of patients.”

Blood-monitoring restrictions are likely one of the greatest impediments to prescribing clozapine, Kelly said. Clozapine was first introduced in the 1970s in Europe, but was withdrawn after the drug was shown to be associated with agranulocytosis—an acute condition that can lead bone marrow to fail to make enough neutrophils (the white blood cells that help fight infection)—a condition known as neutropenia.

As a result, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved clozapine, it mandated stringent blood monitoring of white blood cell and absolute neutrophil counts (ANC). Clinicians are required to draw blood from patients taking clozapine on a weekly basis, and the white blood cell count and ANC must be reviewed by the pharmacy as well as the clinician before the drug can be continued.

“For clinicians and systems of care, the logistics of blood monitoring are clearly a disincentive,” Kelly explained.

In September, the FDA issued modifications to its requirements for blood monitoring for patients receiving clozapine in an effort to lessen the burden on clinicians and patients. As part of these changes, the FDA has clarified and enhanced the prescribing information for clozapine that explains how to monitor patients for neutropenia and manage clozapine treatment.

In addition, the agency announced a new, shared risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) called the Clozapine REMS Program to improve the monitoring and management of patients with severe neutropenia. This program—which requires prescribers, pharmacies, and patients to enroll in a single, centralized program—replaces six existing clozapine registries maintained by individual clozapine manufacturers. Patients who are taking clozapine will be automatically transferred to the Clozapine REMS Program.

Neutropenia will now be monitored by the ANC only, rather than in conjunction with the white blood cell count. The requirements for ANC are also being modified so that patients will be able to continue on clozapine treatment with a lower ANC—a change that will allow continued treatment for a greater number of patients. Patients with benign ethnic neutropenia, who previously were not eligible for clozapine treatment, will now also be able to receive the medicine.

“The revised prescribing information facilitates prescribers’ ability to make individualized treatment decisions if they determine that the risk of psychiatric illness is greater than the risk of recurrent severe neutropenia, especially in patients for whom clozapine may be the antipsychotic of last resort,” the FDA noted in a statement announcing the changes.

However, initiation of the Clozapine REMS has been accompanied by technical and other problems—especially around the ability of clinicians and pharmacies to successfully register for the program. In an announcement issued in late November, the FDA said that it is indefinitely extending the deadlines for provider and pharmacy certification and will issue new deadlines after further evaluation. “We are also carefully evaluating next steps regarding the December 14, 2015, pre-dispense authorization (PDA) launch,” the FDA said in a statement. “We will communicate the revised certification deadlines and additional information about the PDA launch as soon as possible.”

Olfson said he believes that when the initial difficulties with the REMS are overcome, the new monitoring system should be helpful to clinicians treating patients who would benefit from Clozapine. “It simplifies the clinical evaluation of neutropenic events, increases access to clozapine for patients with benign neutropenia, and permits those who develop mild neutropenia to continue treatment,” he said. ■

“Clozapine for Schizophrenia: State Variation in Evidence-Based Practice” can be accessed

here.