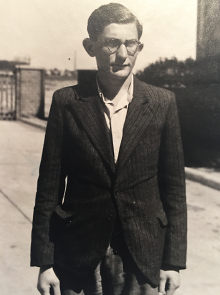

Henry Krystal, M.D., not only lived through the Holocaust, but he transcended its horrors and explored its effects on fellow survivors.

Krystal, who was born in Poland, survived Nazi concentration camps, slave labor, and death marches as a teenager to become a psychiatrist and researcher in America. He died at the age of 90 in October at his home in Bloomfield, Mich.

“Remarkably, he was able to transform his horrific experiences within the camps into insights into the impact of psychological traumatization and the paths that people follow in healing themselves after traumatization,” said his son, John Krystal, M.D., chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine and director of the Clinical Neuroscience Division at the VA National Center for PTSD, among other positions.

“It took a certain kind of courage for Henry Krystal to experience what he did and then recast his life to become a prominent psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and make all the contributions that he did to the study of trauma,” said Robert Jay Lifton, M.D., a lecturer at Columbia University and researcher who has studied the psychological causes and effects of war and political violence, in an interview. “That says a great deal about the man.”

Krystal studied at the Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, after the war. He immigrated to Detroit, completed college and medical school at Wayne State University, and ultimately became a professor of psychiatry at the Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in East Lansing.

His first love in medicine was cardiology and hematology, but he came under the influence of John Dorsey (an analysand of Sigmund Freud) who brought a broad humanistic perspective to psychiatry that Krystal found compelling, said his son.

“He was drawn to the view that you could bring ideas together from psychology, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, philosophy, the arts, and cognitive neuroscience,” he said.

Krystal’s work with Holocaust survivors arose from the many interviews he conducted for the German government as part of the post-war reparation procedure. The process was challenging because no diagnosis existed for posttraumatic psychiatric impairment. Krystal initially published his findings in collaboration with William Niederland, M.D., together laying the groundwork for posttraumatic stress syndromes while advocating for support for survivors.

At the core of his work was the notion that emotions provide critical insights into our internal states that enable us to cope and adapt, but psychological traumatization created such intense distress that the emotions were perceived as overwhelming or even dangerous, said John Krystal.

Emotional life was shut down and emotional situations were avoided. In those moments, people lost insight into their own emotional reactions, seriously undermining many forms of psychotherapy. Krystal developed therapeutic approaches through which people regained the capacity to recognize and tolerate emotional experiences, thus promoting integration of emotional experience in self-regulation and self-healing. Recovering the capacity to experience love and pleasure was critical to the healing process, he wrote.

In an era dominated by psychoanalysis, Krystal was notable in differentiating between childhood and adult trauma and granting significance to the latter, said Anna Ornstein, M.D., another Holocaust survivor who became a psychiatrist and now lives in retirement in Brookline, Mass.

“His point was that adult traumatization had to be distinguished from the devastation that childhood traumatization can have on development,” Ornstein told Psychiatric News. “Adults had the wherewithal to build up defenses against the humiliation and degradation that we suffered in reality.”

Krystal also exemplified the ability for many survivors of trauma to recover and lead meaningful lives, said Ornstein, who, like Henry Krystal, is the parent of two psychiatrists.

“He achieved a great love of life,” she said. “Young people think that we were irreparably damaged, filled with anger and depression, but that was not necessarily the case. People went on living.”

However, they often displayed anhedonia and alexithymia, a lack of feeling, and the inability to verbalize feelings, said psychologist Eva Fogelman, Ph.D., a daughter of Holocaust survivors who has treated child survivors and the children of survivors. Krystal appreciated that they became emotionally numb because they could never allow themselves to fall apart in the camps, no matter how awful their experience.

“In order for psychoanalysis to be successful, patients must accept the events of their lives,” said Fogelman. “But survivors could not accept the persecution and multiple losses they had sustained, and many analysts couldn’t accept that fact.”

On top of that, American psychoanalysts not only resisted post-childhood trauma as an explanation for behavior, but felt survivors’ guilt over their own safety during the war years when confronted by the horrors of the Holocaust, said Fogelman.

“Analysts were afraid of what they might hear, while Holocaust survivors felt afraid they wouldn’t be understood,” she said. “Henry Krystal broke that mutual conspiracy of silence in the psychoanalytic world.”

He broke down other barriers, as well, said Lifton, who in the 1950s studied survivors of the atomic bomb blasts on Hiroshima.

While some scholars who had lived through the camps viewed the experience as unique, Krystal understood that other examples of mass trauma could usefully be compared with the Holocaust, said Lifton.

There were important differences between the two, said Lifton. Hiroshima was an overwhelming, immediate trauma while the Holocaust was sustained over years.

However, there were similarities, he said. Both left indelible images of trauma in survivors, a psychic numbing and a diminished capacity to feel, self-condemnation because they had survived while others did not, a suspicion of counterfeit nurturing in those who tried to help them, and ultimately a struggle to find meaning in the rest of their lives.

Three annual conferences in the 1960s on what Krystal termed “massive psychic trauma” demonstrated his generosity, his openness, and his interest in the work of others, said Lifton.

Krystal’s research on trauma, along with work by Lifton and others, would also inform the understanding in later years of what was termed posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans of the war in Vietnam.

“PTSD was not developed as a concept until 1980, but the idea of survivors and trauma and conflict had been evolving since the 1960s,” said Lifton.

In both his work and his life, Krystal exemplified a way out of darkness for others.

“When you see such resilience in the face of massive psychic trauma, it gives you a sense of hope that one can go on to have a life that is full of actualizing one’s dreams,” said Fogelman. ■

More about child survivors of the Holocaust appears in “Revealed Holocaust Secrets Have Anguishing Impact,” can be accessed

here.