Patients and pediatricians share responsibility for variations from guidelines for community-based care of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), according to data from a study led by Jeffrey Epstein, Ph.D., a professor of pediatrics in the Division of Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“The results of this study suggest that current pediatrician-delivered ADHD care leaves much room for improvement,” wrote Epstein and colleagues in the December 2014 Pediatrics.

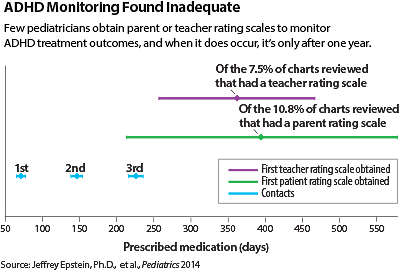

The physicians do a fairly good job of diagnosing ADHD, but could do much better at monitoring patients’ progress in the months and years afterward, said the authors after reviewing 1,594 patient charts produced by 188 pediatricians at 50 Ohio practices.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

“These findings are consistent with what we know in the community,” said R. Scott Benson, M.D., a child psychiatrist in private practice in Pensacola, Fla., who was not involved in Epstein’s study. “Pediatricians know what to do, but they often tell me that they don’t have enough time to do a proper exam or follow-up.”

About 70 percent of the charts in the study documented use of DSM-IV criteria during assessment, but only about 55 percent contained rating scales completed by parents or teachers. Once diagnosed, 93 percent of patients were prescribed medications and 13 percent received psychosocial treatment. However, only 47 percent had a return contact (visit or phone) in the first month of treatment, and average times to collect a parent or teacher rating scale after prescribing were more than a year.

“Psychosocial treatment is very important in the initial phase to teach parents and patients how to manage care,” said Benson, who formerly served on the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s practice guideline committee on ADHD. “Parent training is more important than medication in kindergarten and younger populations.”

Benson, a member of the APA Board of Trustees, said that in his practice, getting feedback from teachers has been hampered by school confidentiality rules and by administrative burdens on both teachers and physicians. He is now experimenting with sending evaluation forms to teachers, who are asked to fill them out and discuss them with parents, who then bring the forms to the clinic at the next visit.

Epstein’s group also found a significant interaction between Medicaid enrollment and academic affiliation. “As the proportion of Medicaid patients at a practice increased, rates of psychosocial treatment increased at nonacademic practices and decreased at academic practices.”

They ascribed that pattern to delays at busy academic centers in scheduling follow-up psychosocial appointments.

“Psychosocial treatments must be available but time limited,” said Benson. “Counseling is helpful but does not change core symptoms. The exceptions arise when treating school performance issues or family conflicts, when targeted counseling is valuable.”

Epstein and colleagues suggested that both doctors and families could do more to improve ADHD care. Physicians should take more responsibility for collecting rating scales during assessment and monitoring and maintaining contacts during the first year of treatment, they said. Pay-for-performance incentives, decision-support tools, or alliances with mental health professionals might assist them. At the same time, patients and families must push for more contact in the second and third years after diagnosis, and more use should be made of teacher and parent rating scales for monitoring.

Finally, physicians could create reminders in their electronic health record systems to help them follow through with ADHD care behaviors, and they could use Web portals to collect rating scales, said Epstein. ■

An abstract of “Variability in ADHD Care in Community-Based Pediatrics” can be accessed

here.