A family history of depression or stressful life events may contribute to altered reactivity in the amygdala during adolescence and a subsequent increased risk for depression, according to a study published online December 19, 2014, in AJP in Advance.

Typically, the amygdala, the brain’s advance warning system, becomes less reactive during adolescent development. Increased amygdala reactivity to images of emotional facial expressions is associated with depression, but whether that occurs before or after the onset of depression was not clear.

So researchers tested 157 adolescents aged 11 to 15 with diagnostic interviews and functional MRI scans twice, two years apart. They evaluated participants with (the high-risk group) and without (the low-risk group) a family history of depression and with and without a history of stressful life events.

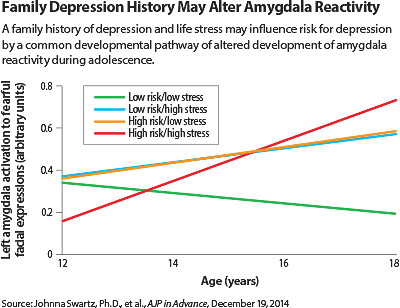

Amygdalae in children with high risk and high stress became more reactive as the children advanced through adolescence. Also, greater amygdala reactivity appeared before the emergence of clinical symptoms, the researchers found.

“Adolescents with a positive family history of depression consistently evidenced a pattern of increasing amygdala reactivity with age, even if they experienced relatively mild life stress in early adolescence,” concluded Johnna Swartz, Ph.D., a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Duke University; Ahmad Hariri, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University; and Douglas Williamson, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry, epidemiology, and biostatistics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The result was reflected in both amygdalae but was significant only in the left.

Participants in the low-risk group not exposed to high stress demonstrated decreasing reactivity, as expected. However, low-risk youth who experienced high life stress had levels of amygdala reactivity similar to those of the high-risk group.

“This interaction suggests that two distinct risk factors—family history of depression and life stress—may influence risk for depression by a common developmental pathway of altered development of amygdala reactivity during adolescence,” said the authors. The change over time suggests that differences in reactivity also increase over time, but the study could not determine whether the changes were also influenced by other factors tied to adolescence, such as puberty or social changes.

The observed effects accounted for only 11 percent of the total variance of amygdala reactivity, leaving room for additional study, of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental influences, said the authors.

Further work also may clarify whether imaging the amygdala might serve as a biomarker of risk prior to the onset of depression or other internalizing disorders and eventually “could be of clinical utility in the early detection of risk,” they said.

This report was part of the Teen Alcohol Outcomes Study, which will follow the young participants through late adolescence into early adulthood, providing more insight into the developmental trajectory of amygdala reactivity.

Funding for the study came from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Genetic and Environmental Risk endowment from the Dielmann Family. ■

An abstract of “Developmental Change in Amygdala Reactivity During Adolescence: Effects of Family History of Depression and Stressful Life Events” can be accessed

here.