Participation in a San Francisco mental health court reduced perpetration of violence by felony defendants over the following 12 months, according to a report in Psychiatric Services in Advance.

In their early days, mental health courts dealt largely with nonviolent misdemeanors. In recent years, more of these special courts have accepted felony cases. Nevertheless, little prospective research is available on how involvement of felony defendants in mental health courts can influence their risk of later violence, said researchers led by Dale McNiel, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine and chief psychologist at the Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital and Clinics.

McNiel and colleagues (including APA President-elect Renȳe Binder, M.D.) compared 88 mental health court enrollees with mental illness with 81 matched jail detainees who received treatment as usual. In both cohorts, about seven of 10 individuals had been arrested on felony charges.

The difference between a misdemeanor charge and a felony may seem quite distinct, but the latter may often reflect just a marginal increase in severity, said Virginia Hiday, Ph.D., a professor of sociology at North Carolina State University, who has studied mental health courts extensively.

“If a theft has a dollar value above the misdemeanor limit or a loitering arrest turns into a shoving match with a cop, the charge will escalate,” Hiday, who was not involved in McNiel’s research, told Psychiatric News.

Participants were not randomized in the current study, so a propensity-score method was used to reduce the effects of potential confounders such as demographic, clinical, criminal-justice involvement, and other factors.

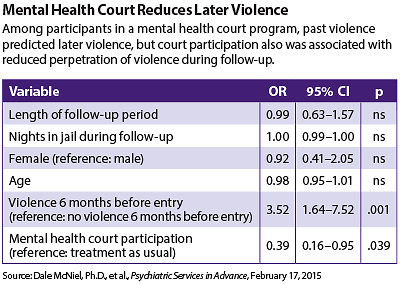

Using both self-report and arrest records, the researchers found that after one year, the strongest association with the likelihood of violence was found among participants with a history of violence in the six months prior to entry (odds ratio=3.52). However, they also found that only 25 percent of the court participants had perpetrated violence, compared with 42 percent of the comparison group (odds ratio=0.39).

“These findings extend previous work by providing prospective evidence that participation in [a mental health court] can reduce the risk of violence among justice-involved individuals with mental illness,” wrote McNiel and colleagues.

Exactly why mental health courts might reduce violence or recidivism remains an open question, they said. It may be obvious elements like mental health treatment, rehabilitation services, or help with housing and employment.

Or perhaps the process itself plays a significant role, said Hiday.

“Things slow down,” said Hiday. “The defendant is treated with respect and is allowed to talk. Everything that goes on is explained, which may not happen in a regular criminal courtroom.”

This idea of “procedural justice” allows people to feel that they’re being treated fairly and so are more apt to cooperate with the system, she said.

Outcomes research like this may help to counter popular beliefs equating violence and mental illness, beliefs that stigmatize mental health courts as well as people with mental illness, suggested McNiel. It also buttresses the view that mental health courts can work with defendants charged with some felonies and improve public safety.

“[T]argeting intensive services to the needs of offenders at higher risk of recidivism yields more demonstrably effective interventions in reducing recidivism,” concluded McNiel and colleagues. The courts can’t achieve this alone, though. “[Mental health courts] considering inclusion of higher-risk individuals need to ensure availability of services to address their needs.” ■

“Prospective Study of Violence Risk Reduction by a Mental Health Court” can be accessed

here.