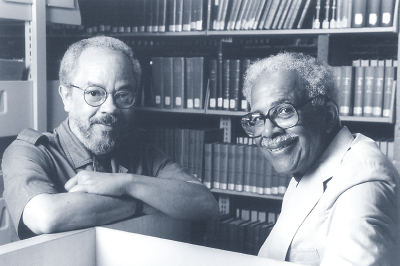

He always referred to himself as “Chet” even in conversations with people he hardly knew. He took his humility to heart, even though he was a full professor on three Harvard faculties (medicine, education, and public health) and had been honored in myriad ways by organizations here and abroad. He was also serious about his commitments, as I learned over many months when I engaged in extended conversations with him on Fridays in his office located in Harvard’s School of Education. He was never late for our meetings. We must have cut a puzzling sight, strolling around Cambridge during our breaks, my diminutive stature next to his 6 feet 4 inches of erect carriage.

He was an assiduous observer of the interactions between blacks and whites in the United States. Chester Pierce tutored me about the imperative of studying how these two groups engaged with each other. Their rituals were a model for understanding oppression in all its forms. He had developed an immutable interest in grasping how the dominant white group sought to control the time, space, mobility, and energy of the nondominant black group. He was intuitively brilliant in his formulations, making it clear that on the one hand, the black-white interaction could be toxic because of the predictable mundane causticity it evoked. On the other hand, however, he knew well that those interactions had an effect at the broader community level. That’s why he talked persistently of racism as a public health pollutant.

It took time for me to recognize that Pierce was, in Hazel Carby’s terms, a 20th century “race man” (See H.V. Carby, Race Men, Harvard University Press, 1998). That is to say, like W.E.B. Du Bois and others, Chester Pierce engaged in racialized thinking, constantly focused on the black-white dichotomy and centered on an ideology that was directly related to race matters in this country. He told me of his participation in the 1968 struggle within APA to make clear the black constituency’s dissatisfaction with the white leadership’s modest interest in blacks and their concerns. But he never wanted to turn the psychiatric association into a flaming cauldron. He sought no distancing of blacks from whites. He wanted to confront whites frankly and plainly, without excessive drama, framing his thoughts about black bodies and minds and how they should be treated. It is he who discussed dignity and autonomy with me, emphasizing the salience of blacks’ controlling the development of their own identities. He had come to that paradigm from the intimate examination of the black-white interaction in behavioral studies of large organizations. He had also examined that interaction through engagement with films and extreme environments.

He helped me understand how many blacks, in repeated traumatic interactions with the dominant group, are battered into conservative and apologetic thinking. Others are simply battered into submission. Despite these observations, he still turned to cultural geography and anthropology to expand his conceptual strategies of coping with extreme environments characterized by inequity and chronic humiliation. He did not give up. He insisted that there had to be ways to create more therapeutic landscapes for all of us to inhabit.

By 1998, when I published our discussions in Race and Excellence: My Dialogue With Chester Pierce (University of Iowa Press), I had become familiar with his family history, academic life, and intellectual approach to problem solving. I had come to understand his fundamental generativity toward young people in our profession, from both dominant and nondominant groups. I had also grasped his antipathy toward selfish theatrics. As our periodic dialogue slowed in recent months, I realized his health was failing, and the time to bid farewell was coming. His absence will be a difficult burden for us in psychiatry who owe him so much. ■