All adults experience some degree of cognitive decline as they get older, a concept known as cognitive aging. A study recently published in Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders has uncovered some evidence to suggest that chronic microbial infections contribute to this subtle cognitive deterioration.

Previous research has shown a connection between cognitive problems and infection—in both healthy individuals and those with mental illness—but as Vishwajit Nimgaonkar, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and human genetics at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) told Psychiatric News, “Most of these data come from cross-sectional studies taken at one time point, so this doesn’t really tell us about cause or effect.”

To examine the long-term effects of infection on cognition, Nimgaonkar teamed up with colleagues at UPMC and Johns Hopkins University to analyze data from a population study called the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT), which conducted cognitive evaluations of a large group of older adults every year for five years. MYHAT also took blood samples at the start of the study, which allowed Nimgaonkar’s group to screen for antibodies against a range of infectious agents.

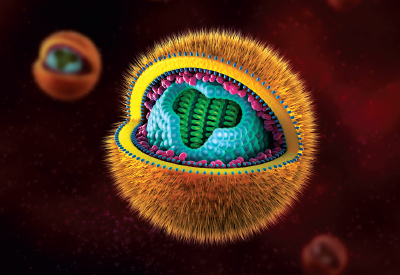

A total of 1,022 participants provided usable blood samples, and the team measured plasma levels of three viruses (cytomegalovirus [CMV], herpes simplex virus 1 [HSV-1], and herpes simplex virus 2 [HSV-2]) as well as the tiny parasite Toxoplasma gondii (TOX)—all of which have shown an association with cognitive deficiencies in previous research.

They then compared how exposure affected cognitive performance both at the start of the study and over the five-year follow-up period.

“We saw that people who were infected did show a different trajectory in their cognitive decline,” Nimgaonkar said. “And it was not uniform. The type of deficits depended on the type of infection they had.”

CMV infection, for example, was associated with greater declines in both memory and visuospatial function; HSV-2 exposure was associated with declines in memory; and TOX exposure was associated with declines in executive function. In contrast, HSV-1 was not associated with any cognitive changes.

HSV-2 also had a strong association with lower cognitive performance at baseline, which the authors noted was unexpected given the paucity of studies into the cognitive consequences of HSV-2 infection.

While there are multiple plausible mechanisms by which infection can damage the brain—from direct effects of viruses entering and damaging brain cells or indirect damage caused by increased inflammation due to viral exposure—Nimgaonkar noted that it is premature to conclude that the infectious agents measured in the study are driving the cognitive problems experienced by the older adults.

“We hope that this study will motivate more research in this area to uncover the mechanisms behind this association,” he said. “I think it would also be interesting to see if antiviral therapy might be protective against cognitive decline.”

Nimgaonkar also hopes that that this work raises more awareness about chronic infections, which are common but are not routinely assessed when evaluating patients for cognitive issues. While there may not be a direct link between the two, it might still be worth extra monitoring or preventative measures if a patient experiencing cognitive decline also has an infection, he said.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Mental Health, and Stanley Medical Research Institute. ■

An abstract of “Temporal Cognitive Decline Associated With Exposure to Infectious Agents in a Population-Based, Aging Cohort” can be accessed

here.