While antipsychotics may offer some short-term help to elderly patients dealing with dementia-related psychiatric problems such as delusions or aggression, they also come with a range of safety concerns for this vulnerable population, including an increased risk of death. What’s more, many population studies have suggested that there is an overreliance on these medications in nursing homes.

In response to such trends, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently mandated that nursing homes reduce the use of antipsychotic drugs by 30 percent. But stopping antipsychotic therapy requires careful consideration as well; for example, a recent study published in the

American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP) that was carried out in several nursing homes in the United Kingdom, found that antipsychotic discontinuation did result in a modest improvement in mortality rates, but it also resulted in a large uptick of neuropsychiatric problems (

Psychiatric News, January 1). However, these problems were ameliorated if the discontinuation was coupled with the addition of personalized social or physical activities for that patient.

“It’s important that patients with dementia have some way to engage their attention and redirect their thought processes as they come off medication,” said Scott Sautter, Ph.D., a practitioner at Hampton Roads Neuropsychology in Virginia Beach and an associate professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

As the AJP study and other research has shown, personalization is a key factor that drives the benefit of social engagement, and traditionally that involves staff getting to know their patients and tailor specific activities around those interests.

That involves a lot of hard work and creativity on the part of the caregivers, however, and as the U.S. population ages, it raises concerns that many senior facilities may not have the manpower or resources to engage residents adequately. And as dementia progresses, many seniors may have great difficulty with traditional social activities.

This, Sautter told Psychiatric News, could present an opportunity for technology to step in.

In a program known as the Birdsong Initiative (named for the couple who sponsored this effort), Sautter and some colleagues have been testing personalized bedside computers as a social engagement tool at the Hoy Nursing Care Center, which is the health care portion of Westminster-Canterbury on Chesapeake Bay, a life-plan community in Virginia Beach.

It may seem a bit ironic as many a person’s first reaction would be to associate extended computer use as an antisocial activity, not to mention a continued perception that new technology and older adults do not mix.

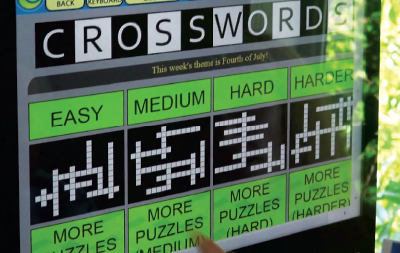

On the latter issue, Sautter acknowledged that some residents did show some resistance as they began implementing the Birdsong Initiative, but overall it has been well received. These touchscreen computers were designed to be as easy-to-use for seniors as possible, with a simple interface, large icons, and even options for voice control.

On the former, he sees these interactive machines not as a social replacement, but as a social stimulant.

“These computers can be preprogrammed to match each person’s interests and life history,” Sautter said. “This includes adding music, movies, or games we know they enjoy, but also things like photos of family members or places they used to live, to keep their memory working.

“The computers also include video chatting features like Skype as well as various social networking programs, which can really assist seniors with mobility issues,” he continued.

As part of the Birdsong Initiative, 62 residents at Hoy with mild to moderate dementia participated in a 24-week study that compared the computer technology with traditional recreational activities. The study was divided into two 12-week segments so every patient would receive both interventions.

While the study did not find any statistical differences between the two approaches, there were some trends to suggest that the computers do provide clinically significant benefits to both patients and caregivers.

“We even saw slight increases in cognition scores in about a quarter of the participants, which is very encouraging,” said Sautter, who is cautiously optimistic about the results of his trial. He noted that this device (which is developed by a company called It’s Never 2 Late) is already popping up in nursing communities across the country, so the current word of mouth seems positive.

An important next step is to see whether bedside computers can provide any benefit to patients with more advanced dementia who are in assisted-living facilities as opposed to living in a community independently.

The programming may have to be more simplistic for such patients, but Sautter sees that as another advantage of the system.

“There are so many possibilities for adjusting these computers not just in terms of content, but also complexity to match the cognitive level of patients and their predisposition to technology,” he said. “And as their familiarity with the system grows, they can add or change features along the way.” ■