Charles Raison, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and the Mary Sue and Mike Shannon Chair for Healthy Minds, Children, and Families at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Human Ecology, has long been fascinated with the connection between body temperature and mood.

It’s a link that’s not often thought of, but people with depression often have temperature-regulation problems and a decreased ability to sweat, and for Raison, this provides a therapeutic avenue. That avenue is heat therapy—raising someone’s temperature to activate thermosensory nerve pathways that travel between the skin and brain.

The concept is not new in holistic circles, but can such an approach help someone with severe depression?

Raison believes so, adding that numerous scientific studies have provided supporting evidence. One in particular was a 2007 study by Raison’s colleague Chris Lowry, Ph.D., now a professor at the University of Colorado, in which he found that injections of inactivated soil bacteria can trigger a large immune response in mice that in turn activated a set of serotonin-producing neurons in their brains and reduced their stress and anxiety.

It is well known that immune activation leads to raised body temperature. So Raison hypothesized, “It might be possible to use heat to appropriate these nerve pathways; in essence, to try to use these pathways as ‘deep brain stimulators’ to produce an antidepressant effect.”

In a study published May 12 in JAMA Psychiatry, Raison, Lowry, and their colleagues provided the first controlled evidence that whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) might indeed be a viable approach to depression treatment.

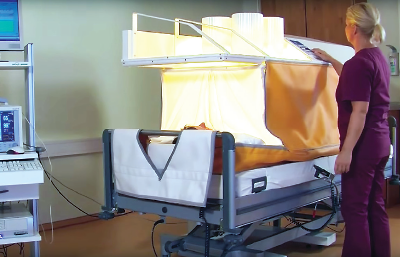

Their study enrolled 34 participants with depression who received one session of either WBH or a sham heat procedure (average length was around 100 minutes). Both set-ups involved placing the participant in a tent-like enclosure—with the head protruding out—in which the whole body is heated through the use of infrared lights, heating coils, and circulating fans. The sham device used non-heat-generating lamps but did have active coils to provide some feeling of heat.

The participants were then monitored weekly for six weeks, and at each point the group that received WBH had lower depression symptoms than the controls. The WBH group scored an average of 6.5 points lower on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression at week 1, and at week 6 the difference was still around 4.2 points.

The side effects were also mild, with typical heat-related symptoms like headache, tiredness, and dry mouth being the most common.

These findings build on a pilot study that found similar improvements in 16 adults with depression given WBH, though that effort lacked a control group and only assessed the patients five days after the heat treatment.

“There’s nothing really magical about this—all you need is the right intensity and duration of heat to do the trick,” Raison told Psychiatric News. “But it should be stressed that these aren’t effects that can be achieved by moving to a warm climate. As I can personally attest, these boxes get hot, hot, hot.”

Specifically, he noted, the air temperature can reach over 135 degrees Fahrenheit, while body temperature can get above 101 degrees Fahrenheit. But the system is designed to make the heating process comfortable. Participants were also carefully monitored to ensure their safety.

“So in theory, spending a couple of hours in a sauna or sweat lodge might produce a similar therapeutic effect, but both would be potentially a good deal more hazardous because these are not controlled environments,” Raison stressed. “However, in a clinical setting, whole-body hyperthermia could someday be used for people who don’t respond to antidepressants or may want a more holistic type of treatment.”

At this point, however, such heating devices are still rare in the United States, and as they don’t have any medical indications from the Food and Drug Administration, they cannot be prescribed off-label for depression. They are used in Europe, and Raison hopes that with more time and research, they will make their way over here.

More work still needs to be done to optimize the procedure, he acknowledged, and test how durable the improvements are.

“The participants undergoing hyperthermia did around 40 percent better in terms of symptoms, and some people even went into remission, but as a whole, this one session did not lead to improvement in everybody,” he said. “And if you looked at the week-by-week scores, it suggests that hyperthermia had some active effects on depression in the first two weeks, but then the improvement was that the patients simply hadn’t relapsed yet. And how long will that last? And will it work better if we give patients two or three sessions instead of one?”

While larger clinical trials may answer these questions—“and in my dreams I hope some major operation might come in and help with the heavy lifting needed to carry out some phase 3 studies,” he said—Raison is also planning on using neuroimaging on people undergoing the procedure to better understand how the hyperthermia is altering both the body and the brain.

This study was supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Institute for Mental Health Research, the Braun Foundation, the Depressive and Bipolar Disorder Alternative Treatment Foundation, and Barry and Janet Lang and Arch and Laura Brown. ■

An abstract of “Whole-Body Hyperthermia for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial” can be accessed

here.