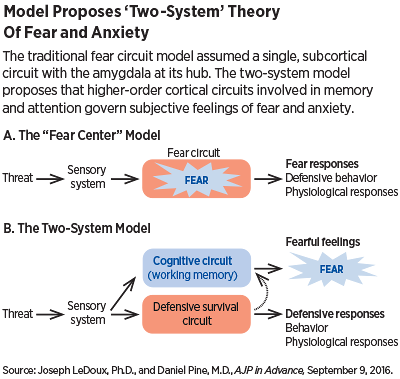

The neuroanatomical understanding of fear has long relied on a so-called “fear circuit” with the amygdala as its hub. This circuit has often been said to be the key to understanding maladaptive fear and anxiety in people with anxiety disorders.

Embedded in the fear circuit theory is an assumption that the subjective experience of fear and the behavioral and physiological reactions to fear (such as the fight-or-flight phenomenon) are products of the same circuit.

Now two leading neuroscientists have proposed, in a landmark review paper in the September 9 AJP in Advance, a conceptual framework that replaces the unitary fear circuit model with a “two system” model—one neurocircuit that governs physiological responses to imminent threats (freezing, racing heart, sweating palms) and another, separate but related circuit that governs the subjective feelings of fear or anxiety that typically compel patients to seek treatment.

In the paper, Joseph LeDoux, Ph.D., director of the Emotional Brain Institute of New York University and the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, and Daniel Pine, M.D., director of the Section on Development and Affective Neuroscience in the National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program, propose that the physiological and behavioral responses to an imminent threat that comprise the fight-or-flight phenomenon are regulated by subcortical neural networks centered on the amygdala and operate nonconsciously.

However, they propose that the subjective experience of fear is regulated by higher order cortical networks responsible for cognitive processes such as attention and working memory. They make the same distinction for anxiety and other emotions—different circuits underlie the conscious feelings of these emotions and nonconsciously controlled behavioral and physiological responses that also occur in tandem.

That’s a crucial distinction, if LeDoux and Pine are correct, because animal models used to test medications for treating anxiety disorders—founded on the more traditional unitary fear circuit theory—may successfully replicate the physiological responses to a threatening situation, but not adequately capture the subjective experience of fear and anxiety as felt by humans.

“The traditional approach has assumed that emotions like fear are products of innate brain circuits inherited from animals,” LeDoux told Psychiatric News. “These circuits are further assumed to give rise to both the subjective feeling of fear and to behavioral and physiological symptoms that also occur. As a result, so the logic goes, it should be possible to develop new treatments that make people feel less anxious by testing whether behavioral or physiological symptoms are reduced in animals. Medications that make animals less timid behaviorally are expected to make people less fearful or anxious.”

That hasn’t worked, he said. “We propose that the reason for this is that the brain circuits that underlie conscious feelings are different from those that underlie behavioral and physiological responses and may require different treatments,” LeDoux explained. “Behavioral and physiological symptoms may be treatable with either medications and/or certain psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, while conscious feelings may have to be addressed with psychotherapeutic treatments that focus on the feelings themselves.”

Experts in anxiety research who reviewed the paper for Psychiatric News said it could be a game changer. “What they are saying that is crucial is that a rodent model of anxiety is probably not going to be able to capture what happens in people,” said Barbara Milrod, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College and an expert on psychotherapeutic treatment of anxiety.

“This is a really important paper,” Murray Stein, M.D., vice chair for clinical research in the Department of Psychiatry at University of California, San Diego, told Psychiatric News. “It’s going to be controversial, in a good way, because it is deliberately meant to shake things up and get those of us who work in this area to think differently about the nature of fear and anxiety. LeDoux and Pine suggest we have been going down the wrong path by looking at animal behavioral models for what we call fear and anxiety, because what we are modeling in animals isn’t what we are measuring, assessing, and trying to treat in humans.”

LeDoux said that doesn’t mean animal research has been useless. “Both sets of symptoms, the subjective conscious and behavioral/physiological, must be understood and treated. And different treatments may be required. Behavioral and physiological symptoms may be treatable with medications or certain psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, while conscious feelings may have to be addressed with psychotherapeutic treatments. Animal research is important and useful, especially if we know how to use it.”

He added, “Our ability to understand the brain is only as good is our understanding of the psychological processes involved. If we have misunderstood what fear and anxiety are, it is not surprising that efforts to use research based on this misunderstanding to treat problems with fear and anxiety would have produced disappointing results.” ■

“Using Neuroscience to Help Understand Fear and Anxiety: A Two-System Framework” can be accessed

here.