People with psychiatric and other medical disorders, as well as jet travelers and shift workers, stand to benefit from discoveries about the biological clock that brought three Americans the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

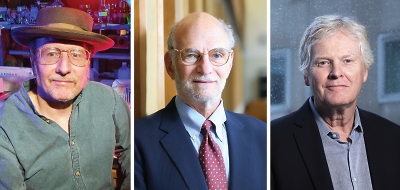

Jeffrey C. Hall, Ph.D., Michael Rosbash, Ph.D., and Michael W. Young, Ph.D., were honored for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm, the Nobel Assembly said in announcing the award last month. Hall is a professor emeritus of biology at Brandeis University; Rosbash is the Peter Gruber Endowed Chair in Neuroscience and a professor of biology at Brandeis University; and Young is the Richard and Jeanne Fisher Professor and head of the Laboratory of Genetics at Rockefeller University, where he also is vice president for academic affairs.

It’s been known for many years that living organisms, including humans, have an internal, biological clock that helps them anticipate and adapt to the regular rhythm of the day, the Nobel committee said.

Hall, Rosbash, and Young “were able to peek inside our biological clock and elucidate its inner workings,” the committee added. “Their discoveries explain how plants, animals, and humans adapt their biological rhythm so that it is synchronized with the Earth’s revolutions.”

The term “circadian” comes from the Latin words circa, meaning “around,” and dies, “a day.” Circadian clocks in cells and tissues throughout the body regulate recurring daily behavioral and physiological processes, including sleep and alertness, hunger, hormone release, blood pressure, body temperature, and reaction times.

“Circadian rhythms are the rhythms of life itself,” observed Daniel Buysse, M.D., the UPMC Endowed Chair in Sleep Medicine and a professor of psychiatry and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“We don’t often think about the fact that we live in two very different worlds: a world of light and a world of darkness,” Buysse told Psychiatric News. “The discovery of clock genes was the key to understanding how life can adapt to these different environments,” he said. “We continue to discover the role that circadian genes play in literally every function of our brains and bodies.”

In 1984, Hall and Rosbash, working together at Brandeis University, and Young, working independently at Rockefeller University, reported that they had isolated PERIOD, a gene that controls the circadian rhythm of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Hall and Rosbash showed that PERIOD encodes a protein called PER that accumulates in the cell at night and dissipates in the day.

The researchers theorized that PER controls the gene’s activity, a role that would require its presence in the cell’s nucleus. In 1994, Young discovered a second clock gene, TIMELESS. Young showed that the protein encoded by TIMELESS, called TIM, partners with PER, enabling both proteins to enter the cell nucleus, creating a feedback loop to orchestrate gene activity. Young also identified a third gene, DOUBLETIME, and its protein DBT, which controls the frequency of ups and downs in protein levels across the 24-hour day.

“Psychiatrists have long been aware of changes in behavior and mood symptoms that occur at different clock times in their patients and that cycle on a daily or multi-day period,” Mary Carskadon, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, told Psychiatric News.

Scientists have identified genetic variants, including components of the clock’s molecular mechanism, that seem to be associated with such psychiatric conditions as bipolar illness and major depressive disorder, noted Carskadon, who directs chronobiology and sleep research at Bradley Hospital in Providence, R.I.

While disturbances of the sleep-wake cycle are most apparent in mood disorders, they also occur in schizophrenia, dementia, and substance use disorders, David Neubauer, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and associate director of its sleep disorders center, told Psychiatric News.

Neubauer said that altered core circadian rhythm genes may trigger early morning awakenings in people with mood disorders, day-night reversal in people with schizophrenia, and sundowning in people with dementia, for example. They also may be related to the underlying pathophysiology of such disorders. The CLOCK gene, he said, has been an especially fertile focus of this research.

“The good news is that manipulations of rhythms have the potential to be therapeutic,” Neubauer observed. Strategically timed sleep deprivation can have an acute antidepressant effect, he said. Regularizing timing of the sleep-wake schedule, meals, and other daily routines may help stabilize mood and prevent relapse.

Jet lag, which involves sleep disruption and malaise, reflects a temporary clash between internal rhythms and the external environment. The Nobel Prize–winning discoveries may spur development of chronotherapies, or timed treatments, such as medications and exposure to bright light for jet lag and other illnesses that disrupt normal synchrony of daily functions.

Beyond fostering the understanding of how disruptions to the circadian system may contribute to psychiatric and medical diseases including obesity, heart disease, and cancer, the laureates’ findings have “had an impact on public policy regarding appropriate school start times and guidelines for shift workers,” Colleen McClung, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News.

“We and others in the field could not do any of the translational work that we do today,” McClung asserted, “without the pioneering work of these Nobel Prize winners.”

The prizes will be awarded December 9 and 10 in Stockholm. The three laureates will share equally nine million Swedish krona, or about $1.1 million. ■

“Scientific Background Discoveries of Molecular Mechanisms Controlling the Circadian Rhythm” can be accessed

here.