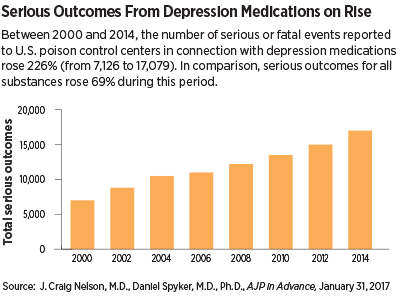

Between 2000 and 2014, the number of serious outcomes, including death, following an exposure to a medication used to treat depression more than doubled, according to an assessment published January 31 in AJP in Advance.

This 226 percent change far outpaces the 69 percent increase in serious outcomes from exposure to any compound during this time and the 18 percent increase in the United States population.

While older antidepressants (tricyclics and MAOI inhibitors) and benzodiazepines contributed to a good portion of these numbers, newer and presumed safer medications like venlafaxine and bupropion also had high morbidity and mortality indices. There were also some unexpected findings, such as the amount of respiratory problems induced by antipsychotics.

J. Craig Nelson, M.D., the Leon J. Epstein Endowed Chair in Geriatric Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, told Psychiatric News that this broad analysis, compiled using the National Poison Data System (NPDS), provides an important 30,000-foot perspective on the poison risks that depression medications pose.

Nelson added that while the number of problems per year has been fast rising, the total numbers and overall rate of serious outcomes are still low for depression-related drugs when compared with other commonly overingested agents like aspirin.

To reflect most medications that a patient with unipolar or bipolar depression might receive, Nelson and co-author Daniel Spyker, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of emergency medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, assessed several other agents beyond antidepressants, including antipsychotics, anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, and lithium; 48 medications were included overall. Three commonly overingested over-the-counter agents (aspirin, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine) were included for comparison.

All instances involving someone calling an NPDS poison control center for one of these medications, whether due to intentional overdose, accidental overdose, or serious reaction to a therapeutic dose, were then compiled for the period 2000 to 2014.

Nelson noted that in the past, doctors were more cognizant of the potential lethality of the older class of antidepressants such as tricyclics and MAOI inhibitors. But when newer and safer agents like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) became available, physicans appeared to pay less attention to issues like overdose, he said.

“We are putting these drugs into the hands of people with depression or bipolar disorder for good reasons, but clinicians should be more aware of the hazards of inappropriate use, which we found vary considerably between medications and do not always align with the risks that are the most publicized,” he said.

For example, Nelson cited the prominent FDA warnings related to the cardiac risks of citalopram that led many to believe it is one of the riskiest newer antidepressants. Yet, on a per exposure basis, his analysis showed that the similar drugs venlafaxine and bupropion had higher mortality indices (9.7 and 7.5 deaths per 10,000 exposures for venlafaxine and bupropion, respectively, compared with 4.2 per 10,000 for citalopram).

Cardiac issues are also a known problem for the antipsychotics quetiapine and olanzapine, which were included in the study along with other non-antidepressants. The analysis revealed that these two medications were linked with relatively high rates of coma and respiratory distress. Nelson noted that the respiratory risks of antipsychotics have been underplayed, but given the growing numbers of people with problems like sleep apnea or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, this side effect should be an important consideration when evaluating medications for patients.

Another important finding that Nelson highlighted from the analysis of NPDS statistics was that amitriptyline, an older tricyclic that was a leading cause of overdose death in the 1970s and 1980s, was still commonly reported to calls at poison centers. During the study period, amitriptyline poisonings (about 38,000 instances) were on par with those associated with citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine. However, amitriptyline accounted for over 3,400 life-threatening events and 145 deaths (37.5/10,000 exposures), which represent 36 percent of all deaths from antidepressant exposure. By comparison, trazodone was involved in over 82,000 exposures between 2000 and 2014, but only 609 life-threatening outcomes and nine fatalities.

Spyker pointed out that overdoses are often impulsive acts, suggesting that this high incidence of problems reflects a ready availability of amitriptyline. “These people are not searching far and wide for a potent agent; they take what’s handy,” he said.

And given the stark morbidity and mortality numbers, both Nelson and Spyker encourage that amitriptyline prescribing should be reevaluated as a public health measure. They noted that amitriptyline is more commonly given now off-label for pain rather than depression, but there are several better options for pain available.

Spyker believes this study can raise awareness and perhaps even lead to changes in FDA warnings before depression-related overdoses become a major crisis.

Nelson did caution, however, that the study looked at only single-exposure poisonings for which the causative agent could be determined. About half of the incidents reported to NPDS involving one of these 48 depression medications also involved exposures other drugs and/or alcohol.

This study was supported in part by the UCSF Leon J. Epstein Fund. ■

“Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Medications Used in the Treatment of Depression: An Analysis of Cases Reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000–2014” can be accessed

here.