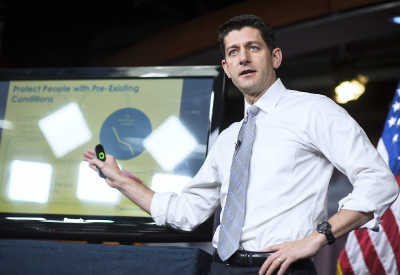

Failing to gain enough votes from his own party, Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), with the approval of President Donald Trump, pulled the American Health Care Act (AHCA) from consideration minutes before it was scheduled for a vote on March 24.

The AHCA was the Republican creation intended to—partially—repeal and—partially—replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA), former President Barack Obama’s signature health care law.

Despite a 22-vote majority in the House of Representatives, the Republican leadership could not corral about 30 ultra-conservative members who said the bill did not go far enough in repealing the ACA. Republican moderates then dug in their heels over the last-minute concessions made by the speaker to appease the hardliners. Among those amendments was ending the requirement to include the 10 “essential health benefits” guaranteed by the ACA as part of Medicaid expansion (although not in the exchange plans for the individual and small group markets)—including mental health and substance abuse services, prescription drugs, and chronic disease management.

Other provisions would have rolled back Medicaid expansion and limited a state’s Medicaid per capita spending, giving states the option to stop covering mental health treatment, thus threatening parity.

Democrats in Congress uniformly opposed the legislation. So did major patient groups, insurers, and medical societies—including APA—which immediately pushed back against the legislation upon its introduction 17 days earlier, concerned that millions of people would lose health insurance coverage or see its cost rise out of reach because of lower subsidies or higher premiums, copayments, and deductibles.

“APA opposed this bill because it would have restricted access to care for millions of Americans with mental illness and substance use disorders,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A. “We will keep advocating for equitable health care legislation that provides patients with the coverage they need and deserve, and we hope that the bipartisan, bicameral cooperation that occurred to pass the 21st Century Cures Act and comprehensive mental health reform will be an example to follow.”

APA activated grass-roots support from psychiatrists around the country to voice their opposition to the bill, said Ariel Gonzalez, J.D., M.A., chief of APA’s Department of Government Relations. “We reached out to Republican offices in the House with our concerns, especially about how the changes to Medicaid could severely cut back access to care for mental illness and substance abuse.”

There was no immediate indication if or when another health care bill might be brought back for a vote, although the Trump administration signaled that it might take administrative steps to weaken the ACA, which remains in force, said Gonzalez.

A study by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found that implementation of the Republican plan would have left 14 million Americans without health insurance within one year and a total of 24 million by 2026.

Among other provisions, the AHCA’s proposed changes for the expanded Medicaid program would have placed caps on funding that held special significance for psychiatric patients.

About 1.3 million people with serious mental illness and 2.8 million with substance use disorders obtained health insurance under the ACA through Medicaid expansion, about almost one-third of the total.

The most severe burden would have fallen on poorer, sicker, and older individuals. Medical facilities also would have been hurt because the amount of uncompensated care has declined under the ACA, former APA President Steven Sharfstein, M.D., who retired last year as president and CEO of Sheppard Pratt Hospital in Baltimore, told Psychiatric News. Taxes on upper-income individuals who helped pay for the ACA would also be cut, shifting the benefits of the AHCA to the wealthy. “The new bill mainly benefits corporations and individuals in the highest income categories because they will be paying less.”

The bill also would have shifted the basis of subsidies from income to age. Under the ACA, older people cannot be billed more than three times as much for premiums as young people. The AHCA would have allowed charging older people up to five times the premium for young people, increasing the burden on older, lower-income people.

The legislation also would have eliminated cost-sharing subsidies and the ACA’s individual mandate to buy insurance. Instead, it would have required a 30 percent surcharge for individuals who have been uninsured for more than 63 days in the preceding 12 months. Such a provision would have disproportionately affected low-income individuals and people with mental illness, who are more likely to go through periods without insurance. The surcharge for not having insurance also would have been age-adjusted, with higher penalties charged to older people.

The bill had retained some provisions of the ACA that APA supports, such as covering preexisting provisions, capping out-of-pocket expenditures, and covering adult children up to age 26 under their parents’ insurance plans. But that was not enough.

“The AHCA would have precipitated a significant erosion in coverage and meaningful access to evidence-based mental health and substance use services,” said APA President Maria A. Oquendo, M.D., Ph.D. “Our mission is to protect those services. APA will continue to work with both Democrats and Republicans on the Hill to ensure that Americans can maintain coverage of mental health care.” ■

The letter that APA sent to congressional leaders opposing the AHCA can be accessed

here.