Yayoi Kusama, now 88 years old and revered as Japan’s greatest living artist, has lived at the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo since 1977.

Painter, sculptor, installation and performance artist, filmmaker, novelist, and poet, Kusama spends most days working in her nearby studio. Her paintings sell for millions of dollars. Time magazine included her in its 2016 list of the world’s 100 most influential people.

“I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art,” Kusama reported in her autobiography Infinity Net. “I followed the thread of art and somehow discovered a path that would allow me to live,” she wrote.

“Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors,” an exhibition of more than 60 of Kusama’s works from the 1950s to the present, drew a record 165,000 visitors to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., this spring.

Organized by the Hirshhorn, the exhibition will open at The Broad in Los Angeles on October 21. From there, it will travel to the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Cleveland Museum of Art, before ending its North American tour at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in February 2019. A Kusama exhibition simultaneously is touring Japan.

Born in 1929 in the small city of Matsumoto, Kusama was the youngest of four children in a middle-class family. Although her father bought her art supplies, her mother viewed painting an unsuitable pursuit for a girl and ripped up her pictures.

Around age 7, Kusama began hearing pumpkins, violets, and dogs talking to her. She often saw auras around objects and bursts of radiance along the mountainous skyline that made objects around her flash and glitter.

“Whenever things like this happened, I would hurry back home and draw what I had just seen in my sketchbook,” she recalled in her autobiography. “Recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes. That is the origin of my pictures.

“Psychiatry was not as accepted in my youth as it is now,” she added, “and I had to struggle on my own with the anxiety, to say nothing of the visions and hallucinations that at times overwhelmed me.”

Although Kusama persuaded her parents to let her attend art school in Kyoto, she hated the traditional master-disciple system there. Finding respite in the home of a poet, she diligently painted pumpkins and won prizes in local art shows. Pumpkins, which she regards as a source of energy, remain a frequent focus of her work.

Kusama’s first solo show in 1952, when she was 23, featured the infinity nets that are among her hallmark images. Thousands of tiny white arcs on a black background cover these early canvases. A gauzy wash overlays the nets, evoking Kusama’s report of often being “tormented by a thin, silk-like curtain of indeterminate grey that would fall between me and my surroundings.”

A visitor to Kusama’s first show, the late Shiho Nishimaru, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Shinshu University in Matsumoto, got to know Kusama. He presented a paper on her at a psychiatric conference that year, “Genius Woman Artist With Schizophrenic Tendency.” Kusama reports Nishimaru also encouraged her to leave home. “If you remain in that house,” she said he told her, “your neurosis will only worsen.”

In 1955, fascinated by a book of paintings by U.S. artist Georgia O’Keeffe, Kusama sent O’Keeffe 14 watercolors. O’Keeffe sent these paintings to gallery owners, whose interest drew Kusama to the United States in 1957.

She lived for a few months in Seattle, where a gallery had agreed to show her work, and soon moved to New York. She often painted 50 or 60 hours straight. “I would cover a canvas with nets, then continue painting them on the table, on the floor, and finally on my own body,” she reported. “As I repeated this process over and over again, the nets began to expand to infinity.”

Kusama awakened one morning to find nets she had painted the previous day seemingly stuck to the windows. As she reached to touch them, she felt they crawled on and into her skin. This experience triggered what she terms “a full-blown panic attack.” She called an ambulance that took her to Bellevue Hospital—a trip she began making every few days. Doctors there eventually suggested she enter a mental hospital. She opted to keep painting.

It was also in the 1950s that Kusama started painting her now-famous polka dots. As a child, Kusama said that she stared for hours at millions of white pebbles in the riverbed behind her home. Of her paintings, she said, “I wanted to examine the single dot that was my own life. One polka dot: a single particle among billions.” Repetition of the dots, she explained, helps “obliterate” her anxieties.

In her performance art, some of which she also filmed, she often applied polka dots to both her own body and the naked bodies of people she recruited as actors. Active in the pop-art scene in New York in the late 1960s, Kusama led anti-tax and anti-Vietnam War protests featuring naked participants. She associated with Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and other well-known artists.

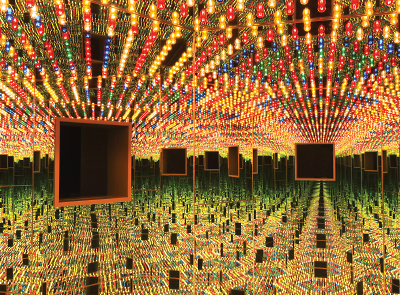

Six of Kusama’s 20 Infinity Mirror Rooms, which she started to make in 1965, give the touring show its name. These rooms feature mirrored walls, floors, and ceilings and flashing lights. Some contain polka dot balloons, pumpkins, and other objects. Some include a pool of water; some have sound tracks. A viewer’s every move generates kaleidoscopic images, fostering a sense of floating in space that can be both exhilarating and unsettling.

The traveling exhibition concludes with “The Obliteration Room,” a conventional domestic interior furnished with chairs, lamps, a television, books, and other items, initially all white. Visitors receive a sheet of colored dots to affix where they like, joining Kusama in creating a new work of art.

Kusama returned to Japan in 1973 and voluntarily entered the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill in Tokyo in 1977. For her rare public appearances, Kusama usually sports a flame-red wig and polka dot dress. ■

More information on “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors” can be accessed

here.