The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued guidance to clarify when mental health professionals can share information with patients’ loved ones, particularly in emergency situations such as after an overdose or other mental health crisis, without running afoul of federal privacy regulations.

The guidance, issued by the HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR), comprises new fact sheets, FAQs, and charts for mental health professionals, patients, and family members explaining privacy rule provisions under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The new guidance fulfills requirements of the 21st Century Cures Act to clarify the privacy rule and is not intended to amend existing standards, according to OCR.

OCR created two web pages—one for professionals and one for consumers—that are intended to provide a “one-stop shop” on HIPAA privacy regulations. The information for professionals focuses on helping to mitigate the risk of the patient harming himself or others, respond to opioid crises, and handle disclosures related to minors.

HIPAA was enacted in 1996. In the past decade, the number of privacy violations has ballooned—in 2015, HHS received 18,000 complaints, up from 7,000 in 2005.

“For many years since HIPAA was enacted, we’ve noticed confusion among providers concerning what information should be shared with whom and what special permission is needed for that sharing,” Harsh K. Trivedi, M.D., chair of APA’s Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing and CEO of Shepard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, told Psychiatric News. “Anything that makes it easier for providers to do the right thing and allows them to share critical information with patients’ loved ones is always welcome.”

Providers often take the most conservative stance when it comes to information sharing, which is not always beneficial to clinicians or patients, Trivedi added. “It’s not just the disclosing of information that is important, but in an emergency, collecting information from loved ones can be vital in determining treatment and next steps in care.”

While OCR has made a good effort at clarifying the privacy rule, more fine-tuning is still needed, Debra A. Pinals, M.D., chair of the Council on Psychiatry and Law and director of the Program in Psychiatry, Law, and Ethics at the University of Michigan at Ann Harbor, told Psychiatric News. “Even with the guidance, privacy regulations are still very complicated, and despite the new FAQs, charts, and flow diagrams, not every patient scenario is covered,” Pinals said. For example, people with mental illness in the justice system may have histories that get lost between facilities, which can create continuity of care issues.

New Guidance for Professionals

OCR clarified in its guidance that the privacy rule doesn’t require written permission for providers to disclose information; the permission can be verbal or implied, based on circumstances. In all cases, providers should only share information “directly relevant” to the loved ones’ involvement in the patient’s care—for example, asking the close friend of a patient in crisis to take her to a psychiatric consult or pick up a new prescription for her, OCR wrote.

Under HIPAA, if a patient is mentally incapacitated, a professional has the discretion to decide that disclosing protected information to involved family, friends, or caregivers is in the patient’s best interests, even if the patient is unable to agree, according to OCR. Such circumstances may include when a patient is experiencing temporary psychosis, is unconscious, or under the influence of drugs.

One new fact sheet included in OCR’s guidance is aimed at helping professionals handle situations in which patients are threatening harm to themselves or others. The fact sheet reaffirms that “mental health professionals need to be able to use their expertise and professional judgment to identify a potential or likely risk and determine who can help lessen the potential for harm.”

Disclosures are also permitted to law enforcement, family members, or others when the provider perceives “a serious and imminent threat” to the safety of the patient or others and those notified are “in a position to lessen the threat.” For example, if a patient tells his psychiatrist that he has persistent images of harming his spouse, the provider may notify the spouse, develop a plan for hospitalization, and call 911 or law enforcement.

OCR noted that it “would not second-guess a health professional’s judgment about when a patient seriously and imminently threatens [his or her] own, or others’, health or safety.” Trivedi particularly appreciated this statement. It suggests that OCR “is taking into consideration the clinical aptitude or expertise that the provider is bringing to the table,” he said.

Guidance Related to Opioid Crisis

A new fact sheet discusses HIPAA privacy regulations for professionals treating patients for opioid overdoses. It lays out a narrow set of circumstances under which providers may share information about an opioid overdose or opioid abuse disorder without the patient’s permission: (1) the patient must be incapacitated or unconscious; (2) the provider must determine it is in “the best interest” of the patient to disclose; and (3) the information must be “directly relevant” to the family’s or friend’s involvement in the patient’s care. Patients who regain their decision-making capacity hours after an overdose, for example, must then be offered the option to decide about any additional disclosures.

The difficulty with the privacy rule, Trivedi said, is that it must balance the need to share information during a true emergency while also trying to protect an individual’s privacy and civil liberties. Providers simply may not be able to meet all of the specified conditions. “The nature of an emergency is you are working with some or few of the facts. … You may not be able to ensure every one of these points is met because you have to start helping the person.”

The guidance explains that a provider can disclose a patient’s opioid use under certain circumstances, for example, if the patient poses a threat to his own health by continuing to use opioids upon discharge and the informed person might be able to help.

Both Trivedi and Pinals said that guidance is needed on how the HIPAA opioid guidance interplays with 42 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 2, which sets a higher bar for sharing information on patients being treated in any federally assisted alcohol or substance use program.

Among other provisions, Trivedi said that 42 CFR Part 2 requires that substance use treatment records be kept separate from the rest of a patient’s medical file. That separation can result in an individual’s obtaining a prescription for an opioid from another provider who has no way of knowing the individual is being treated for substance use.

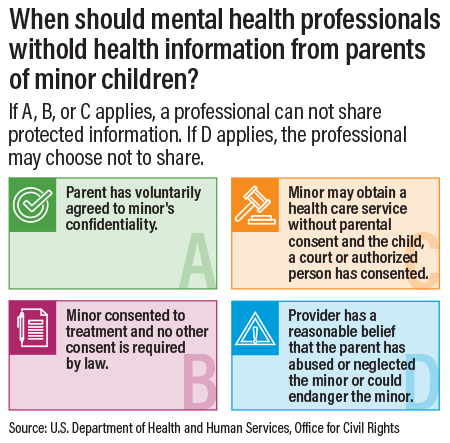

A new OCR infographic spells out when a parent is not considered the minor child’s “personal representative” and is not automatically entitled to obtain protected health information from mental health professionals. ■

The new HIPAA privacy page for mental health professionals can be accessed

here. “Additional FAQs on Sharing Information Related to Treatment for Mental Health or Substance Use Disorder—Including Opioid Abuse” are available

here.