After being given a green light by the Trump administration, a number of mostly Republican states are overhauling their Medicaid programs to restrict enrollment and benefits, such as requiring work, limiting lifetime coverage, and adding hefty monthly premiums.

Mental health and consumer advocates are concerned that the 10 million enrollees with mental illness who rely on Medicaid will be shut out of coverage—and treatment—as a result. States have broad discretion in how they structure these plans, yet most do not have effective systems to exempt vulnerable people, including those with mental illness and substance use disorders, from work requirements and other new provisions, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) said in a news release.

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership and serves as a critical safety net for 1 in 5 Americans, most of whom live in poverty. It is the nation’s single largest insurer and covers a disproportionate share of individuals with complex, disabling illnesses. The changes to the states’ Medicaid plans are being allowed under part of the Social Security Act known as Section 1115, which allow states to waive certain rules to offer new services or expand the population covered.

Late last year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidance that new 1115 waivers no longer had to increase a state’s population covered by Medicaid. Then on January 11, the agency said it will support states’ efforts to test whether work or community engagement requirements might promote better health for enrollees and help them “rise out of poverty and attain independence.”

Kentucky and Indiana were the first to gain approval to require Medicaid enrollees to work as a condition of eligibility, a first for 50-year-old Medicaid (pending in eight more states). But welfare programs, such as food stamps and cash assistance, have long been tied to working. The work rule and other new restrictions seek to recast Medicaid as a welfare program, rather than a health coverage plan, and will test the bounds of administrative discretion for these waivers, said Robin Rudowitz, an associate director with the Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF) Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, at a briefing for reporters. The first lawsuit over the work requirements was filed January 24 against the Trump administration by a group of Kentucky Medicaid enrollees who are seeking to block the state from implementing its waiver and to stop CMS from allowing work requirements.

APA, along with a group of five frontline physician organizations, is urging state and federal authorities to “first, do no harm” to future or current enrollees when considering these new requirements and restrictions, which it called “outside the objectives of the Medicaid program.”

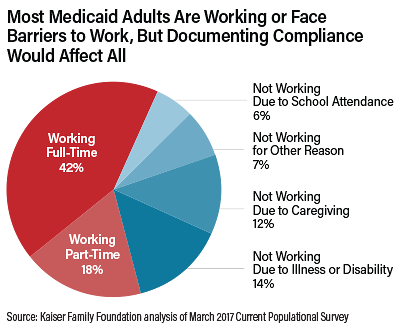

About 60 percent of Medicaid enrollees are already working, and most other enrollees face barriers that would exempt them from the new work requirements, such as disability (14 percent), school attendance (6 percent), and caregiving (12 percent), according to KFF.

“This leaves a small segment of the population, only about 7 percent, for whom these new work requirements would apply,” Rudowitz said. “But it would affect most enrollees, because most would need to document their work status monthly or would have to navigate a difficult process to obtain exemption.”

Effect on Enrollees

Under federal law, Medicaid work requirements and some other restrictions must exempt adults who are elderly, pregnant, “medically fragile,” or eligible for Medicaid because they receive Supplemental Social Security. However, there are many adults on Medicaid who are unable to work due to illness but who do not meet the federal standard for disability. These individuals are likely to be subject to the work requirements and other eligibility and coverage restrictions.

“The important thing to remember, it’s not just meeting the work requirement; it’s about documenting and verifying each month that you met the requirement, or if you are exempt, it’s about verifying that you meet the exemption status,” Rudowitz said. Such administrative procedures are costly for states to implement and leave much “wiggle room” about what qualifies as a serious mental illness or a serious and complex medical condition, she added.

Such procedures may be especially difficult to navigate for people with mental illness. “Rather than spending limited public resources on enforcing mandatory work requirements, NAMI urges states to invest in robust, evidence-based supported employment programs that many people with mental illness need to get and keep competitive employment,” NAMI wrote in a release.

Frederick Isasi, executive director of Families USA, said the “array of cynical paperwork requirements” in these plans are designed to take coverage away from people. Kentucky’s “waiver continues a profound and deeply saddening departure from our nation’s commitment to the health of our families,” he said. ■

APA’s joint statement with other front-line physicians on demonstration waivers and other proposals to change Medicaid benefits can be accessed

here.