Do colleges and universities have a responsibility to protect students from violence that may be perpetrated by other students with mental illness?

That’s the question at the heart of a recent California Supreme Court ruling. This past March, the California Supreme Court found that students have a reasonable expectation that universities will provide a safe environment in classrooms and laboratories, including protection from violence perpetrated by students who may be mentally ill.

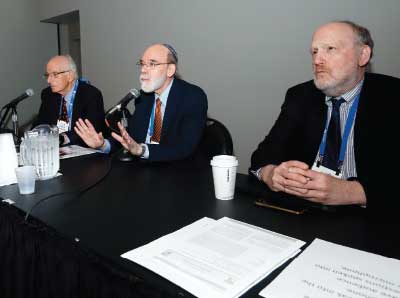

At a symposium at APA’s 2018 Annual Meeting in New York, past APA President Paul Appelbaum, M.D., said that although the ruling in Rosen v. Regents of the University of California applies only to institutions in California, it is likely to be looked at with interest by other states where colleges and universities are concerned about violence on campus.

The effect of the ruling on how colleges and universities may view students and applicants for admission who have a history of mental illness is unknown. “The concern is that it will heighten universities’ attention to troubled students—not in a good way—and make them less willing to admit, retain, or re-admit them,” said Appelbaum, who is also the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and director of the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “Student mental health services may face greater pressure to identify ‘risky’ students, and students may be more likely to withhold information about mental health treatment or avoid campus mental health services altogether.”

Appelbaum was joined at the symposium by Howard Zonana, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and adjunct professor of law at Yale University, and Marvin Swartz, M.D., chair of APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, which organized the symposium. Swartz is also head of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine. The panelists discussed separate cases addressing the question of whether correctional facilities have a responsibility to provide discharge treatment planning for released detainees who have mental illness and the standards that should be applied to determine intellectual disability in cases involving the death penalty. In each of these cases, APA submitted an amicus brief.

Rosen v. Regents may have the broadest impact. In fall 2008, Damon Thompson transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Not long after, he began to complain—to professors and others—that other students were making derogatory comments about him. He later wrote a letter to the dean of students saying that students in the dorm were making unwelcome sexual advances, spreading rumors, and teasing him. He warned that if something wasn’t done, the situation would “escalate.”

He was moved to a new dorm, but the following semester his complaints continued. In February 2009 he complained of hearing voices coming through the dorm walls calling him an “idiot.” He also claimed to hear students “clicking” guns in a threatening way. When campus police arrived, he was taken to the emergency room and diagnosed with schizophrenia. Thompson agreed to take a low dose of an antipsychotic medication and was referred to the campus mental health service, where he was evaluated by a psychiatrist and had several sessions with a campus psychologist.

However, in March 2009 he threw away his medication and a month later withdrew from treatment. The following September he returned to campus and told a chemistry lab professor that other students were interfering with his experiments. On October 7, the director of campus mental health met with the dean of the school and a campus crisis response team to discuss what to do about Thompson. But the following day, he attacked the student next to him in the laboratory, Katherine Rosen, stabbing her in the chest and neck with a kitchen knife.

Rosen was seriously injured but survived. She sued the university, dean of students, chemistry professor, and psychologist alleging negligent failure to protect, warn, or control the attacker. UCLA moved to dismiss the case on the grounds that colleges have no duty to protect adult students from criminal acts and made a motion to dismiss. A trial court denied the motion, and an appellate court granted the motion. Also, the court found the psychologist exempt from liability because the California statute requires that there be an explicit threat made against a specific person.

The case went to the state Supreme Court. The amicus brief filed by APA, the California Psychiatric Association, and the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists was confined to the relatively narrow issue of supporting the psychologist’s exemption from liability. That exemption was upheld by the Supreme Court.

However, the court ruled that “a special relationship” exists between a university and its students and that students have a reasonable expectation that universities will provide a safe environment in classrooms and laboratories. That duty applies when harm from a particular student is reasonably foreseeable in a curricular setting.

Appelbaum explained that the broader implications of the court’s ruling have to do with how universities and colleges may regard students with a history of mental illness. “UCLA argued that colleges would have an incentive not to provide extensive mental health services,” Appelbaum said. “It’s the ‘see no evil’ defense—if you don’t provide services, you can’t know that someone might be a threat, and you can’t be held liable. The university also claimed colleges would be more likely to suspend or expel students with mental illnesses.”

Appelbaum said the court dismissed these concerns, saying the Americans With Disabilities Act and “market forces” would constrain colleges from discriminating against students with mental illness.

“It remains to be seen how that will play out,” he said. “The court’s ruling is limited to California, but it may influence courts in other states.” ■

APA amicus briefs can be accessed

here.