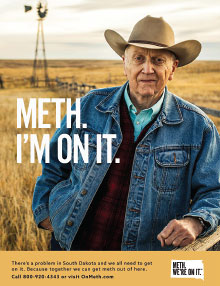

South Dakota was skewered on social and mainstream media over its nearly $1.5 million methamphetamine prevention campaign launched last month, in which healthy residents, ranging from football players to farmers simply state, “Meth. I’m on it.”

Republican Gov. Kristi L. Noem asserted the campaign is “working” because more people are talking about the problem of methamphetamine use, but is this enough?

Elie G. Aoun, M.D., general, addictions, and forensic psychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at New York University, said he found the motto confusing. “The way it sounds is ‘We’re taking meth,’” he pointed out. “Is this an advertisement that is promoting meth use? When we’re in an era when people are just skimming headlines, this campaign doesn’t inspire people to educate themselves about the methamphetamine problem or to get help.”

According to nationwide data, annual overdose deaths from psychostimulants including methamphetamine grew nearly eightfold from 2000 to 2017, when there were more than 10,000 deaths. About half of those deaths also involved opioids.

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that about 1.6 million individuals reported past-year methamphetamine use in 2017. However, these numbers mask the wide regional variability in the prevalence of use, which is greatest in the West and Midwest. More than 70% of local law enforcement agencies from the pacific and west central United States report methamphetamine is “the greatest drug threat” in their area, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

In South Dakota, more than four-fifths of the state’s court admissions for controlled substances this year involved methamphetamine, Noem said. “It impacts every community in our state and threatens the success of the next generation,” Noem said in a statement. “It is filling our jails and prisons, clogging our court systems, and stretching our drug treatment capacity while destroying people and their families.”

Aoun said North and South Dakota’s methamphetamine crisis arose in part because of the nature of the fracking industry prevalent there, which requires young men to leave their families and any social support network behind for months at a time. At the same time, the region has a huge local and imported production of methamphetamine.

The South Dakota campaign’s website, OnMeth.com, encourages people who want to help those suspected of using methamphetamine to “report” them, but doesn’t say to whom. For individuals who are seeking help for methamphetamine use disorder, the site provides little more than a link to the state’s Department of Social Services, which offers a list of clinics.

“Finding these resources isn’t the problem; it’s getting people motivated enough to seek treatment,” Aoun said. “This campaign fails to address the underlying issues, such as lack of social support, and it doesn’t lay the structure of who’s going to identify the people at risk or suspected of using methamphetamine.”

Aoun said another major shortcoming of the campaign is its failure to address another critical aspect of treatment: HIV and sexually transmitted disease prevention. Methamphetamine increases libido and lowers inhibition, resulting in high rates of infection among users, he said.

The state’s Department of Social Services paid nearly $450,000 to an ad agency this fall for the campaign, with plans to pay $1.5 million in total. That amounts to three times more than Noem’s requested Fiscal 2020 budget of $1 million for methamphetamine treatment. A spokesperson told Psychiatric News that the success of the campaign will be measured by how many people view it, text the helpline, and/or are referred to treatment.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, South Dakota is one of 15 states that have applied for or imposed work requirements in their Medicaid program, the safety net health insurance for the poor. If approved by the Trump administration, Medicaid enrollees in the state who fail to work 80 hours a month—or to file required notifications of their work—will lose their health coverage.

“When methamphetamine use becomes very severe, it impacts a person’s ability to go to work and earn a living. That’s when patients need Medicaid the most. Restricting access to it defeats its purpose,” Aoun said. “They can’t say ‘Look at what we’re doing to help,’ but also limit access to treatment for people who are … most desperate.”

Treatments Available

While there are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of methamphetamine addiction, there are medications that can make patients feel more comfortable as they begin treatment and address co-occurring psychiatric illnesses, which many patients have, Aoun said. The antidepressant mirtazapine is effective for reducing withdrawal symptoms, and antipsychotic medications can help manage methamphetamine-induced psychosis, he added.

According to NIDA, the most effective therapies for methamphetamine addiction at this point are behavioral, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and contingency management interventions. The latter offer patients in treatment a chance to win cash rewards or prizes when abstaining from drugs. Such programs have been used successfully at VA hospitals and other health care systems. ■

South Dakota’s website on meth is

OnMeth.com; the TV commercial is posted

here. Information about U.S. methamphetamine use is posted

here.