Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are distinct childhood conditions, but they share many traits. Children with both disorders often display impulsivity, difficulties with social skills, and repetitive behaviors. A study published December 10, 2018, in JAMA Pediatrics identified a hereditary overlap as well. Children who have an older sibling who has been diagnosed with ASD are not only at an increased risk of ASD themselves, but also at an increased risk of developing ADHD. Similarly, children who have an older sibling diagnosed with ADHD are at an increased risk of being diagnosed with ADHD or ASD.

“[L]ater-born siblings of children with ASD and ADHD appear to be at elevated risk within and across diagnostic categories and thus should be monitored for both disorders,” wrote lead author Meghan Miller, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, and colleagues. “Practitioners may wish to share such information with families given the potential relevance of monitoring social communication, attention, and behavior regulation skills in later-born siblings of children with ASD or ADHD.”

Miller and colleagues analyzed medical records from two large U.S. health care systems: Wisconsin’s Marshfield Clinic and Kaiser Pacific Northwest, which covers Oregon and Washington. They looked for families who had at least one more child after having a child diagnosed with ADHD or ASD. The authors did this to overcome the effect of “reproductive stoppage,” in which parents decide to stop having children after one is diagnosed with a developmental disorder. Family analyses that look only at the total number of siblings with or without a disorder likely underestimate the true inheritance risks, the authors wrote.

The final dataset included 15,175 non-firstborn children; of these, 730 had an older sibling diagnosed with ADHD (the ADHD risk group) and 158 had an older sibling diagnosed with ASD (the ASD risk group).

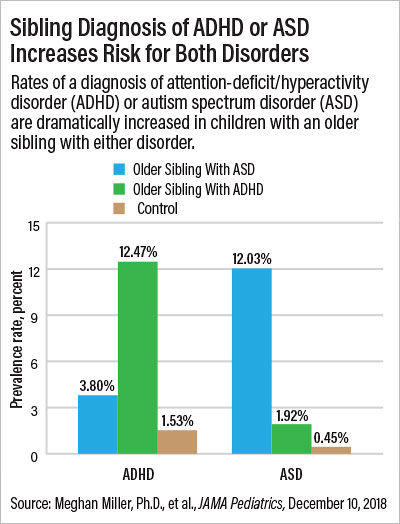

Compared with children whose older siblings had neither disorder, children in the ASD risk group were about 30 times more likely to also be diagnosed with ASD and 3.7 times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD. Children in the ADHD risk group were about 13 times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and 4.4 times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than children whose older siblings had neither disorder.

Overall, about 15 percent of later-born siblings in the ADHD and ASD risk groups were diagnosed with ADHD or ASD, compared with about 2 percent of children whose older siblings had neither disorder.

Miller told Psychiatric News that the analysis could not rule out that some of the increased prevalence of ADHD and/or ASD among the siblings in the ASD and ADHD risk groups was due to shared environmental factors. However, she said there is a lot of evidence that shows these two disorders are highly heritable.

As expected, the odds of ASD or ADHD in later-born siblings increased even more if the child was a boy. In the ADHD risk group, the odds of an ADHD diagnosis in a later born sibling also increased if the older diagnosed sibling was a girl.

“Some studies have suggested that there may be a ‘female protective effect’ for male-predominant disorders like ASD and ADHD,” Miller told Psychiatric News. That means females need to inherit a greater amount of genetic risk factors before they manifest a disorder. Therefore, if a daughter develops ADHD, it suggests the parents are carrying a greater genetic burden, which would make ADHD in boys more likely. The authors did not observe this same trend with older female siblings in the ASD risk group, which they suggested may have been due to the smaller number of diagnoses in the dataset.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health. ■

An abstract of “Sibling Recurrence Risk and Cross-Aggregation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder” can be accessed

here. “Later Sibling Recurrence of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Clinical and Mechanistic Insights,”

here.