“I tell what I have seen—painful and shocking as the details often are,” wrote Dorothea Dix in 1843. “I proceed, gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of insane persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience.”

With that mix of emotion and description, Dix began the crusade that would consume the rest of her life and make her a legend in the history of American psychiatry.

“Combining passion, knowledge, and sheer determination, she insisted that the state had a moral, humanitarian, medical, and legal obligation toward the mentally ill to provide the benefits of asylum care,” wrote Gerald Grob, Ph.D., in The Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill.

In the end, she was “responsible for founding or enlarging over 30 mental hospitals in the United States and abroad,” said Grob. That is a one-dimensional perception of her life, however.

Dorothea Lynde Dix was born in Hampden, Maine (then a part of Massachusetts), on April 4, 1802, to Joseph and Mary Dix. Her father was the impoverished son of a wealthy landowner. She was emotionally and possibly physically abused by her parents, wrote David Gollaher, Ph.D., in his Voice for the Mad: The Life of Dorothea Dix. Dix was so deeply scarred by her childhood that she left no written description of her experiences in her voluminous writings.

“Eventually, it was her own fierce sense of privation that enabled her to identify so passionately with the mad, who she unfailingly portrayed as the homeless and abandoned of America,” wrote Gollaher.

She left home at age 13 to live with various relatives in Worcester and later in Boston with her wealthy grandmother, Dorothy Dix. To earn money and find a place for herself in the world, young Dorothea began a career as a self-educated teacher. After a few years, she wrote Conversations on Common Themes, a reader for elementary students, followed by several religious books for children.

In the mid-1830s, Dix came to see teaching as a dead end and fell into a physical and psychological crisis. Friends suggested the cure lay in a sea voyage and time in Europe. Upon landing in Liverpool, she stayed with the family of the English Unitarian merchant and philanthropist William Rathbone III at Greenbank, his estate outside the city.

At Greenbank she found the warmth, acceptance, and kindred souls missing from her own family. The Rathbones not only had a social conscience, but also the means to do something about it. Dix met English social reformers like Samuel Tuke, the grandson of the founder of the York Retreat, the archetype in Britain of enlightened “moral treatment” of the insane.

Improved in mind and body, she returned to Boston in 1837. Her grandmother had died, leaving her a modest inheritance on which she could live. There, Dix began teaching women in the East Cambridge House of Corrections. The experience gave her an insight into the squalid lives of prisoners, some of whom were considered insane. She traveled around the state, asking jailers and others in local communities about conditions. She saw that mentally ill individuals were housed in jails with criminals.

Her investigations were distilled into her classic work, the “Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts.” She listed, town by town, the details she had recorded: “Lincoln. A woman in a cage. Medford. One idiotic subject chained, and one in a close stall for 17 years. Pepperell. One often doubly chained, hand and foot; another violent; several peaceable now. Brookfield. One man caged, comfortable. Granville. One often closely confined; now losing the use of his limbs from want of exercise. Charlemont. One man caged.”

Not everyone concurred, however. Many local officials felt her descriptions were exaggerated or unfair, even when they agreed on the need for facilities other than jails to house and care for people with mental illness.

Her advocacy in Massachusetts would be repeated in other states. Once she collected data, she wrote a report appealing to the highest moral and practical instincts of lawmakers. The population was growing in the young United States, and the kinds of services once handled by a family or a village now required public institutions backed by the resources of the states. Dix would frequently live for weeks or months in a state capital and work to persuade lawmakers to vote to establish and fund the asylums in which she so deeply believed.

Paradoxically, Dix’s influence was due to the inferior status in which women were held at that time. They could not vote and did not serve in government. Middle- and upper-class women, at least, were supposed to be modest, nurturing creatures whose role in life was caring for hearth and home and doing good works. Dix did not challenge those expectations but fulfilled her conventional role on a much larger scale by persistently expressing concern for society’s downtrodden.

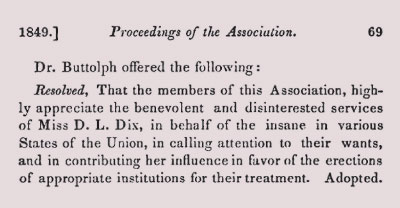

Dix’s work was predicated on a belief that most patients were curable. Some asylum directors like Samuel Woodward, the first president of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, claimed substantial cure rates. Dix would argue that proper care could allow many of the insane to function one day in their home communities. Later, studies by Pliny Earle (the Association’s president in 1884-1885) and others would show that these results were overblown. The reports counted as “cured” anyone who was released from the institution and didn’t calculate readmissions. Many of the superintendents were ambivalent about Dix’s work, wary of her outsider status but hopeful for an improved mental health system. The Association passed a resolution in 1849 honoring Dix’s work.

After Massachusetts, Dix traveled from state to state, inspecting jails and asylums and writing up her findings for legislatures.

In 1844 she went to New Jersey where physicians and a state commission had long advocated for a new state asylum. She shifted from the melodramatic appeals that worked in Massachusetts to “calculation, professional opinion, and legal argumentation.” Effective lobbying led to legislation signed into law in March 1845, paving the way for the approval of the New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum in Trenton.

Her findings and her presence in state capitols led to reforms and new construction. She was particularly welcomed in the antebellum South. Southerners saw her as one reform-minded Northerner who did not insist on lecturing them about slavery. And slavery was probably Dix’s most notable intellectual blind spot. By all accounts, her sympathy for the downtrodden did not extend as far as considering African-American slaves as fully human beings.

“Of a woman so thoroughly inspired by moral conviction, one must ask why the dictates of her conscience moved her to speak out boldly on asylums and prisons, yet evaporated when they confronted the most profound and bitterly divisive moral issue of her century,” said Gollaher. “Dix’s failure to connect the rights of society’s deviants—the poor, the criminal, and the insane—and the rights of all other people, black and white, worked in the long term to her disadvantage.”

Dix eventually went to Washington, D.C., to do on a national level what she had done at the state level. She urged Congress to set aside millions of acres of federal land to be sold off over time to finance construction of asylums and care for the indigent insane. Her Ten Million Acre bill was finally passed by both the House and Senate in 1854, only to be vetoed by President Franklin Pierce. Pierce saw it as an encroachment on states’ rights and an undesirable expansion of a federal role in social welfare policy.

“She had failed in her greatest fight,” wrote Gollaher.

Dix spent the Civil War as an unpaid superintendent of nurses caring for wounded Union soldiers in Washington, D.C. She proved unsuited for this task. The very independence that served her well in the past left her unprepared to function well within a government or medical system.

After the war, it soon became clear that the grand state asylums were becoming less temporary homes for mentally ill people on their way to recovery than custodial institutions for the incurable poor. As asylums filled up, the afflicted were shunted off to jails, prisons, and almshouses. It was a bitter completion of the same vicious circle that Dix set out to break at the start of her career.

Still later, as her inheritance dwindled, she was granted use of a private suite in the New Jersey State Hospital in Trenton, the very edifice that she had helped to build. She died there on July 17, 1887, and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass., under a simple stone marker bearing only her name. ■

Much of the information for this article was gleaned from David Gollaher’s book Voice for the Mad: The Life of Dorothea Dix (The Free Press, New York, 1995). A selection of Dorothea Dix’s writings can be accessed

here.