Investigators at Yonsei University in Korea and colleagues have devised a method of measuring amyloid-beta (Aβ) particles in the blood that can distinguish people with Alzheimer’s disease from healthy controls with more than 90% accuracy. While the study was small and further research is needed, the findings represent an important potential breakthrough.

Aβ is present in the blood as well as the brain in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, but using this molecule as a biomarker poses significant challenges. First, Aβ molecules frequently stick together to form clumps of various sizes, sometimes even attaching to other molecules, which makes it difficult to quantify how much Aβ a person has. The bigger challenge is that Aβ does not have a straightforward relationship with Alzheimer’s. Many adults with elevated Aβ levels are cognitively fine, while others have limited amyloid buildup but still develop Alzheimer’s.

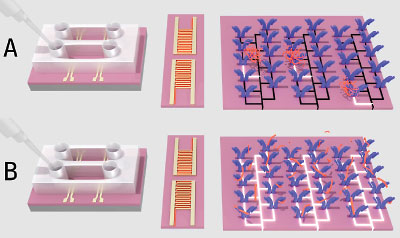

The Korean team hypothesized that the concentration of Aβ in a person’s blood is not critical to Alzheimer’s pathology; the more important indicator is how “sticky” the amyloid is—does it exist in small fragments or large clumps? To test their hypothesis, they divided 106 blood samples—61 from adults with diagnosed Alzheimer’s and 45 from controls with no cognitive problems—into two groups. Half of each sample was left as is, while the other half was pretreated with an acidic chemical called EPPS that breaks up Aβ clumps into single molecules. The two aliquots were then dropped onto a biosensor that used amyloid-based antibodies to assess relative Aβ concentrations of untreated and EPPS-treated blood.

When the researchers compared the average plasma Aβ levels in both untreated and EPPS-treated blood samples, they found no noticeable differences between Alzheimer’s patients and controls. However, they did observe that EPPS treatment greatly increased the average concentration of Aβ in Alzheimer’s blood samples; this supported their idea that Aβ in patients with Alzheimer’s is stickier and more readily clumps together.

So, the researchers divided the two measurements for each blood sample group (untreated and EPPS treated) to come up with a “stickiness” ratio for each individual.

Using a ratio cutoff of about 1.2 or higher to indicate Alzheimer’s, the investigators could differentiate patients with Alzheimer’s from healthy controls with more than 90% accuracy overall (93% chance to correctly identify an Alzheimer’s sample and 97% chance to correctly identify a healthy sample).

What’s more, the researchers identified a possible correlation between the “stickiness” ratio size and disease progression; that is, Alzheimer’s patients with higher ratios (which equates to larger Aβ clumps prior to EPPS treatment) were more likely to have worse cognition as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Exam. This suggests that this new blood test may be able to both identify individuals with Alzheimer’s and track disease progression.

As the investigators acknowledged, this work is still preliminary. A 90% accuracy rating is excellent in diagnostic terms, but the 106-person sample size is considered small. In addition, the samples came from two distinct groups: patients with clinical Alzheimer’s and patients with no cognitive problems. It remains to be seen if this blood test can differentiate a patient with Alzheimer’s from someone with mild cognitive impairment or someone with non-Alzheimer’s dementia.

Henrik Zetterberg, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and neurochemistry at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and a specialist in Alzheimer’s biomarkers was intrigued by this biosensor but felt the researchers used the wrong antibody to capture the Aβ fragments.

“Because of this, they cannot tell which form of amyloid-beta they are measuring,” he said, referring to the fact that Aβ fragments can be either 40 or 42 amino acids long. Though these two versions are nearly identical physically, they are biologically different; many researchers believe the relative abundance of Aβ40 versus Aβ42 is critical for Alzheimer’s progression.

Zetterberg added that the investigators might have even measured some amyloid precursor protein—a nontoxic protein that gets chopped up to create Aβ fragments. “This makes it hard to draw any solid conclusions from the paper,” he said.

This study was published April 17 in Science Advances and was supported by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology, National Research Foundation of Korea, Asian Institute for Life Sciences, and Yonsei University. ■

“Comparative Analyses of Plasma Amyloid-b Levels in Heterogeneous and Monomerized States By Interdigitated Microelectrode Sensor System” can be accessed

here.