Rising suicide rates since the 1990s have been felt across American communities and cultures: for example, among Black adolescents, suicide attempts rose by 73% between 1991 and 2017, according to a 2019 study in Pediatrics, while injury by attempt rose 122% among adolescent Black boys.

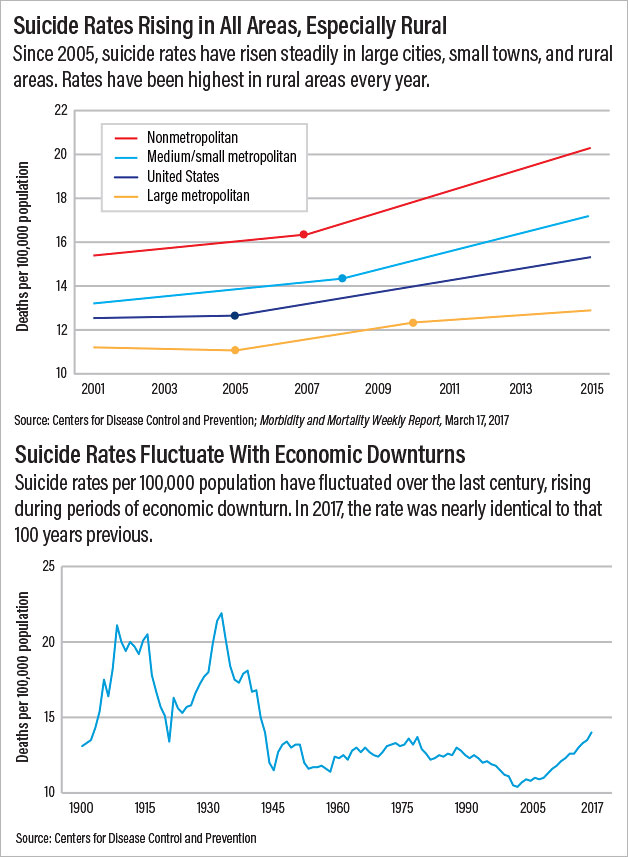

In large cities, small towns, and rural communities across the United States, the number of suicides has risen steadily between 2001 and 2015, but it has consistently been higher in rural counties than elsewhere.

Altogether more than 47,000 Americans died by suicide in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

What is driving these trends?

Certainly, any number of acute, internal stressors may immediately precede a suicide; ultimately, it may be impossible to wholly fathom why any one individual is driven to take his or her life.

Yet behind every suicide there is often a common backstory of shame and/or guilt and a surrounding context of social, cultural, economic, and political factors that shaped the actions of a suicide victim, according to psychiatrist and psychoanalyst James A. Gilligan, M.D. Gilligan presented a keynote address at a virtual conference last month titled “Suicide, Culture, and Community,” which was sponsored by the Erikson Institute for Education and Research at the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

Gilligan compared the rising rates of suicide, roughly the same as a century ago (with episodic increases), with the enormous progress that has been made to reduce the number of accidental deaths—for example, through better workplace design, improvements in automobile design, and seatbelt requirements. And he asserted that equivalent preventive mechanisms should be employed to prevent suicide.

“What we have mislabeled as ‘accidents’ were not accidental at all,” he said. “They were, and still are, the predictable result of conditions that are identifiable and preventable.”

This is also true, he said, of suicide, a problem requiring “public health and preventive medicine, including preventive psychiatry.”

‘Mattering’ Matters in Suicide

At the virtual conference, Gilligan and other clinicians and suicide researchers explored the psychosocial, cultural, and political factors that drive suicide in a range of different communities—racial and sexual minority communities in the United States, Japanese youth who populate an online community focused around suicide, rural communities in the Berkshires where Austen Riggs is located and in upstate New York, and a high school in a wealthy, predominantly-White American suburb.

They also looked at how community organizations and faith-based communities are successfully responding to suicide. (Further coverage of the conference will appear in future editions of Psychiatric News.)

Prominent in all of the presentations was the importance of addressing loneliness, social isolation, and alienation in a digital world and the need for “mattering” to instill a sense of social purpose and community belonging.

Especially salient was the influence of gender and the adverse effects of patriarchal values that compel men to act out on shame and/or guilt in the form of suicide or homicide and inhibit vulnerability or their ability to seek out help (see box).

Encompassing and impacting all of these is the political and economic environment. Commenting at the start of the virtual conference, historian Thomas Kohut, Ph.D., a member of the Council of Scholars at the Erikson Institute and conference co-director, said, “At-risk people themselves often understand suicide not as an individual personal act, but as a profound social, cultural, and at times even political act and a social, cultural, and political form of communication.”

Suicide Follows Socioeconomic Tide

Gilligan cited three socioeconomic variables that have been shown to correlate with each other and also with rates of both suicide and homicide: the rate and duration of unemployment; the frequency, depth, and duration of economic contractions; and the rates of relative poverty or degree of economic inequality, as measured by the size of the gaps in income and wealth between the rich and the poor.

“It is understandable that these economic downturns expose those who are suffering … a loss of socioeconomic status to intense and sometimes overwhelming degrees of shame and humiliation, feelings of failure, and [feelings of] defeat,” Gilligan said. “It is hardly surprising that all three of those [factors] have also been shown to predict the increases and decreases in the rates of both suicide and homicide.”

Additionally, he noted that individuals who do not have health insurance die earlier and suffer more disability than those who have insurance. Meanwhile, the United States is the only country in the developed world without universal health coverage.

He asserted that these trends matching socioeconomic downturns with rising suicide and homicide rates can be correlated with specific policies, and he especially singled out the policies of successive Republican administrations and the efforts of the Trump administration to dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

“In the medical profession, many doctors have been advocating evidence-based medicine,” he said. “If we want to reduce the rates of suicide and all other forms of death in our society, we need evidence-based politics.”

In closing, Gilligan cited the 19th century German physician Rudolph Virchow, M.D., a prominent social reformer in the German parliament, who said, “Medicine is a social science, and politics is simply medicine on a larger scale.”

Gilligan called for a collective political agenda focused on “reverence for life.” “Our mission to prevent suicide is not only a professional vocation [as] mental health professionals,” he said. “It is also a political vocation, and in the largest sense of the word, a religious vocation, which is based, as all medicine worthy of the name is, on reverence for life.” ■