Studies have shown that the most frequent reasons parents first seek psychiatric treatment for their children are problems with severe irritability and/or aggression, which often manifest alongside attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). These symptoms can also be vexing for physicians, since there is not much clinical research exploring childhood aggression.

The good news is that in most cases, childhood aggression can be tempered with well-managed stimulant therapy, said Joseph Blader, Ph.D., a child and adolescent clinical psychologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

Blader was lead author of a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry that examined the question of how best to manage childhood aggression. His group enrolled 175 children aged 6 to 12 with ADHD and a co-occurring conduct disorder for a two-stepped trial.

“Setting out, our goal was to get as many kids into the randomized part of the trial as possible,” Blader told Psychiatric News. All enrolled children had to have significant aggressive behavior despite currently or very recently taking a stable dose of stimulants for at least 30 days—an effort to ensure the participants were not responding to the medication. (Significant aggressive behavior was defined as a score of ≻24 on the parent-reported Retrospective-Modified Overt Aggression Scale, or R-MOAS.)

In the first part of the trial, all the children received a systematic adjustment of a stimulant each week to find the best tolerated dose. In the second part, any children whose aggressive symptoms did not improve at the optimal dose were randomly assigned to receive the antipsychotic risperidone, the mood stabilizer divalproex, or placebo in addition to their stimulant medication for eight weeks. The children and their parents received behavioral family therapy during both phases of the trial.

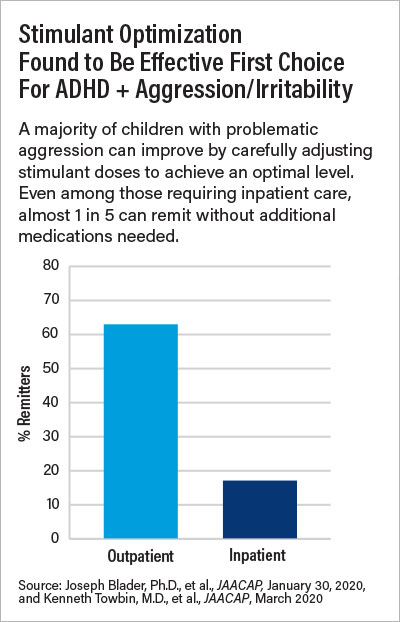

Ninety-six of the 151 children (63%) who completed the stimulant optimization phase—which took an average of 69 days—achieved a remission of their aggressive symptoms (defined as a R-MOAS scored of ≺15) on stimulants alone.

In the second phase of the trial, children taking either risperidone or divalproex had statistically greater reductions in their aggression symptoms than those taking placebo. Due to the small sample size, though, the researchers could not determine whether risperidone or valproate was superior at reducing aggression. Children taking risperidone experienced more weight gain than those taking divalproex or placebo.

“This is yet another study that demonstrates how powerful stimulants alone can be for numerous behavioral symptoms,” said Kenneth Towbin, M.D., chief of clinical child and adolescent psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Intramural Research Program. “It validates stimulants as the first-line intervention to reduce irritability and aggression in children.”

Blader said that because child and adolescent psychiatrists are in such high demand, pediatricians and other family physicians can play a key role in optimizing stimulants for youth with ADHD and aggression. Proper stimulant titration can help to effectively triage and reduce the number of children referred to child and adolescent psychiatrists for specialist care to those with the most complex symptoms, he said.

As for those children with ADHD and co-occurring aggression issues who don’t respond to stimulants alone, Towbin suggested some strategies to identify a good add-on medication: “Make sure to look at the whole profile of symptoms beyond the hyperarousal. If you see signs that resemble autism, such as social isolation or communication deficits, then an antipsychotic like risperidone might help in the short term,” he said. “If the child shows more internalizing problems like depression or anxiety, then you can go with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor like citalopram.”

The potential of citalopram as an add-on therapy for children with ADHD was recently demonstrated by Towbin and his colleagues at NIMH in another study in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. In an effort that took 10 years, the researchers enrolled 103 children with severe and chronic irritability (enough to require hospitalization) for their own two-stepped study. As with Blader’s trial, the children were first optimized on stimulant therapy, and then nonresponders were randomized to receive add-on citalopram or placebo. Once again, many children improved on stimulants alone, but for those in the randomized phase, more children responded to citalopram than placebo (35% vs. 6%, respectively).

“The overall degree of improvement was modest, so citalopram is not the best thing since sliced bread by any stretch,” Towbin said. “But it does open a promising treatment possibility for some children.”

Towbin added that when his trial started in 2008, there was still a lot of concern that these irritable children had an early onset form of bipolar disorder and giving them an antidepressant might trigger mania. “But not a single one of our children developed a manic episode, so I think we can put that false conceptualization to rest,” he said.

Blader’s study was funded by grants from NIMH and National Center for Research Resources. Towbin’s trial was funded by the NIMH Intramural Research Program. ■

“Stepped Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Aggressive Behavior: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Adjunctive Risperidone, Divalproex Sodium, or Placebo After Stimulant Medication Optimization” is posted

here.

“A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Citalopram Adjunctive to Stimulant Medication in Youth With Chronic Severe Irritability” is posted

here.