COVID-19 Takes Heavy Psychological Toll On Health Care Workers

A study out of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in China reports that more than half of nurses and physicians working in hospitals in the Wuhan region have symptoms of depression and psychological distress. The findings were published in JAMA Network Open.

The authors surveyed 493 physicians and 764 nurses from 34 hospitals in China equipped with fever clinics or wards to treat COVID-19 between January 29 and February 3. They assessed the survey respondents’ depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress using the Chinese versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale, the Insomnia Severity Index, and the Impact of Event Scale–Revised.

More than half of the survey respondents (50.4%) reported depression symptoms, 44.6% reported anxiety, 34.0% reported insomnia, and 71.5% reported psychological distress. Health care workers directly engaged in the diagnosis, treatment, and care of patients with COVID-19 were more likely to report each of the above symptoms compared with those not directly involved.

“Protecting health care workers is an important component of public health measures for addressing the COVID-19 epidemic. Special interventions to promote mental well-being in health care workers exposed to COVID-19 need to be immediately implemented, with women, nurses, and frontline workers requiring particular attention,” the study authors wrote.

Protein May Promote Depression Resilience In Women

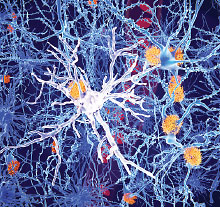

The activity of an immune-related protein called CD300f might protect women from developing major depression, suggests an animal study in PNAS.

Researchers at the Institut Pasteur in Montevideo, Uruguay, and colleagues first identified this immune connection in a genetic analysis of 485 individuals with major depression and 625 depression-free controls. They found that women, but not men, who had a genetic variant in the CD300f gene had more than a 30% decreased risk of depression compared with women without this variant. CD300f encodes a receptor found in microglia—cells that help protect and repair neurons.

To further investigate the relationship between CD300f and depression, the investigators developed mice that lack CD300f. These mice did not show any significant signs of inflammation damage in the brain, but female mice had altered gene expression in their microglia and increased activity of some inflammatory chemicals compared with mice with the gene. These mice also exhibited more depression-like behaviors than mice with the gene. When the CD300f-lacking mice were given an injection of a bacterial protein to trigger an immune reaction, they exhibited even more depressive behaviors, suggesting immune proteins were contributing to the depression.

These findings suggest that the genetic risk factors underlying depression exert their effect not only through changes in neuron activity, but also changes in supporting brain cells, the investigators wrote.

Novel Compound Might Make Serotonin-Targeting Drugs More Effective

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen and colleagues have identified a compound that they believe may increase the therapeutic potency of antidepressants that target the serotonin transporter. Such an adjunct compound could enable physicians to prescribe lower doses of antidepressants.

This preclinical study was published in Nature Communications.

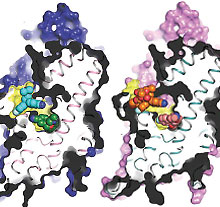

The discovery was made possible following the computation of the 3D molecular structure of the serotonin transporter. The 3D model revealed that there were two regions that impacted the binding of antidepressants to the transporter: in addition to the primary antidepressant binding site, the researchers discovered an allosteric site. The researchers in this study showed computationally that if a molecule attaches at the allosteric site, it changes the receptor structure to make antidepressant binding at the primary site easier.

The researchers next scoured a pharmaceutical drug library and found a chemical called Lu AF60097 that could bind the allosteric site tightly. When they administered this chemical in combination with the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine to rats, they observed it led to greater serotonin release than imipramine alone after 40 minutes to 60 minutes. The serotonin levels remained elevated for the duration of the analysis (160 minutes).

It might be possible “to lower the therapeutic dose of [imipramine] by co-administering an allosteric binder such as Lu AF60097, preserving the positive effects of tricyclic antidepressants on major depressions while reducing the detrimental side effects such as cardiac arrhythmias and [cardiac] arrest,” the investigators wrote.

Stimulants Help Cognition By Shifting Motivation For Work

Stimulants like methylphenidate are used by people without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as cognitive aids. A study appearing in Science now reports how these drugs likely exert their cognitive effects.

According to the analysis by researchers at Brown University and colleagues, stimulants—which block dopamine reuptake to keep circulating levels of this neurotransmitter high—do not directly boost cognitive ability. Rather, stimulants shift motivation so that the perceived benefits of performing a demanding task outweigh the costs.

The researchers came to this conclusion after performing an assessment of 50 healthy adults aged 18 to 43. The participants were asked if they would perform a set of cognitive tasks of varying degrees of difficulty in exchange for money; the more demanding the task, the bigger the reward. The researchers calculated the “indifference point” for each participant (the difficulty level at which a participant’s motivation to make money or avoid work were about equal). All participants also had their dopamine levels in the brain assessed with MRI imaging.

The researchers found that adults with higher dopamine levels in their caudate nucleus (part of the brain’s reward center) were on average willing to perform more complex tasks.

Next, the participants performed the same tasks after taking either methylphenidate or sulpiride (another dopamine receptor inhibitor). Participants with lower levels of dopamine at baseline were more willing to perform more complex tasks after taking methylphenidate or sulpiride compared with when they took placebo. These medications did not appear to affect the behaviors of adults with higher dopamine levels at baseline. ■