When the COVID-19 outbreak in China was revealed and the epicenter Wuhan was locked down, we, a group of 45 psychiatrists and mental health professionals, assembled a team (TopGun Peer Support Wuhan) on January 24 to provide peer support for the Wuhan health care professionals (HCPs) who were fighting at the front lines of this crisis. The majority of the team members worked from overseas, and

one member was in Wuhan.

We employed intervention techniques using social media that achieved good results according to the feedback from the Wuhan HCPs. This innovative approach can be widely applied, is ideal for rapid response, and is suitable in situations of lockdown or quarantine. This approach can be developed into an easily modifiable model that can be applied immediately to help battle the pandemic now roaring in United States.

We used a social media app named WeChat as our venue to carry on communications with HCPs in Wuhan from overseas. WeChat is the most popular social media app in China—based on a Statista.com November 2019 report, it had 1.1 billion users compared with 1.6 billion for WhatsApp, a similar app popular in the Western world. Other popular social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram are banned in China; hence, WeChat was the easiest and most widely accepted platform for our team to directly reach out to the Wuhan HCPs.

We strictly defined our scope of practice as providing peer-to-peer support of HCPs. Using an on-call system, members voluntarily signed up for two-hour shifts, covering up to 16 hours daily.

We set up two chat rooms; one was named “TopGun Volunteer” for use by team members only, and the other one was named “Wuhan frontline HCP peer support.” This chat room reached about 300 local HCPs and became our main work platform for engaging with them and providing support. We utilized group therapy techniques along with some unusual approaches such as self-disclosing to engage Chinese HCPs and then provided peer support in a private chat room with consent. We employed techniques such as active and reflective listening, validation, mindfulness, and other cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing during the intervention.

Engagement was the most difficult part, which might be due to multiple reasons, including distance from the HCP, chat room setting, trust issues, lack of feedback at least in the beginning, stigmatization, and fear of political repercussion. The team took time to engage and build up rapport, and more Chinese HCPs reached out for help over time.

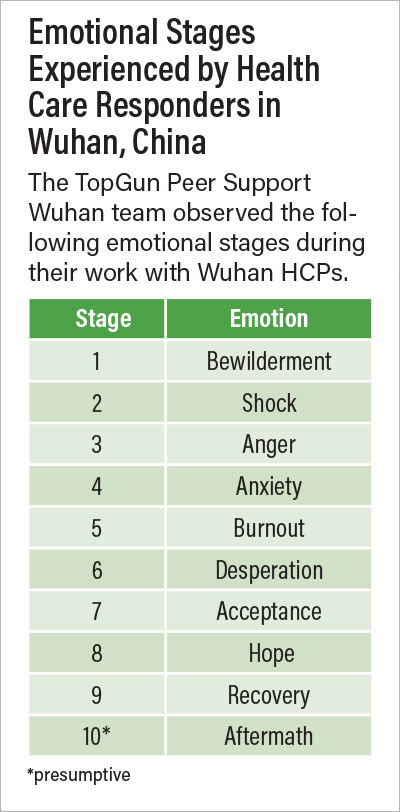

As part of our work, our team identified 10 stages of reaction to the crisis (see table). Our team provided support to HCPs through the emotional stages of 3 to 9. We finished the project when they were all in stage 9, and on follow-up, we found no need for referral for long-term intervention; however, we did offer information about local mental health services.

Feedback from the Chinese HCPs indicated that the project was overwhelmingly successful and helped them cope with significant emotional stress and traumatic experiences. Hence, we believe this model of intervention might also help HCPs in the United States during the active phase of the pandemic and secondary mental health crises in its aftermath. Our team is writing a practical manual for the model, which we have named the Assertive team-Time limited-Peer support (ATP) model.

Here are several important lessons we learned from our Wuhan project experience:

•

Frontline HCPs experienced multiple stressors during the crisis, including fear for their safety and that of their family’s, the frustration of lacking supplies and administrative direction, conflicting treatment guidelines, witnessing traumatic scenes, and feeling guilty for not saving patients. Such experiences and feelings can lead to a secondary mental health crisis, which needs intervention promptly. Therefore, trying to mitigate these stressors early can significantly reduce the negative mental health impact on health care workers.

•

We found that stages 3 and 4 were the best time points to intervene—before HCPs slid into burnout (stage 5) and desperation (stage 6), which may have already occurred in areas such as New York City and reduced the number of functional health care workers.

•

“Do no harm” is the top priority for such services. Mental health professionals must be qualified and use professional tools, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and crisis intervention techniques; otherwise, HCPs might experience further emotional damage.

•

Multiple formats can be used to provide interventions. A telephone hotline is one example. Our Wuhan project used social media, which we believe could be of much wider use if HIPAA limitations are addressed. Institutional intranets or a website can also be considered.

•

The key features to improve the engagement of health care workers to services are easy accessibility and the option to remain anonymous. The goal is to reduce barriers and break down resistance.

•

The ability to make local referrals to psychiatric care is a must for HCPs who need immediate care (such as for suicidal ideation or behavior) or long-term intervention (such as for posttraumatic stress disorder).

As the pandemic continues and finally winds down, we can expect many HCPs and the general population in the United States to experience mental health problems. Therefore, our goal, as psychiatrists and mental health professionals, is to flatten the mental health crisis curve; otherwise, it might further paralyze our health care system and even society to a certain degree. ■