There is abundant epidemiologic and genetic data supporting a close connection between alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression. A study in Frontiers of Behavioral Neuroscience now adds neurological data to support this connection. Using laboratory mice, investigators at Pennsylvania State University uncovered changes in the activity of a class of neurons that helps regulate mood after the animals were forced to abstain from drinking alcohol.

What’s more, there were clear distinctions between male and female mice, noted lead investigator Nicole Crowley, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biology at Penn State. Following abstinence from alcohol, female mice experienced greater changes in SST neurons (neurons that release the hormone somatostatin) than males in response to stressful stimuli.

“We know that women are somewhat more likely than men to drink to relieve work-related or personal stress,” Crowley said. “This new study supports that idea by providing one mechanism by which stress and alcohol interact in females.”

Crowley and her team developed a model of forced abstinence for this study. One group of mice had free access to two bottles—one with water and the other with alcohol; the alcohol concentration was gradually increased from 3% to 10% over the course of 42 days, at which point it was taken away. A control group of mice received only water in the two bottles for the duration of the study.

The investigators then conducted a series of behavioral tasks over the next 21 days; the tests were spaced out to try to capture the progression of alcohol withdrawal. In the first few days following abstinence, mice were given tests to assess anxiety—commonly experienced in the early stages of alcohol withdrawal—while subsequent tests assessed depressive symptoms. Analysis of brain tissue was then performed after the final test: a forced swim test that assesses coping skills.

As previous studies have shown, the mice with access to alcohol developed a preference for alcohol over water. Once they were forced to abstain, both male and female mice exhibited depressive-like behaviors, but with some observable differences between the sexes. For example, abstinent male mice spent more time immobile after being placed in water for the forced swim test than their female counterparts. Crowley pointed out that this does not necessarily mean that male mice became more depressed during abstinence; it is possible that, like humans, male and female mice cope with certain stressors in different ways.

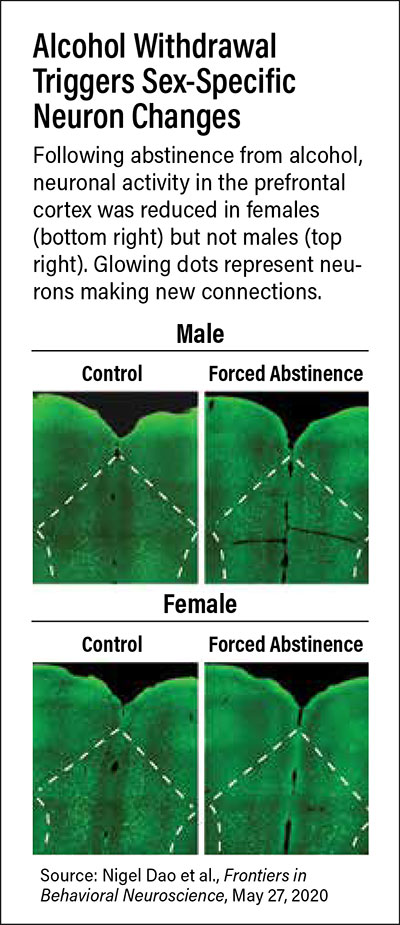

The brain tissue analysis confirmed that males and females had different neural responses to the forced swim test. Crowley and colleagues observed that the female mice forced to abstain from alcohol had lower levels of overall neural activity than males in two brain regions: the prefrontal cortex (the center for complex functions like language, social behaviors, and decision making) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), which coordinates stress-related signals across the brain to effectively respond to threats. However, while SST neuron activity in these regions remained the same in male mice who were forced to abstain from alcohol compared with controls, the activity of these cells differed in abstinent females. Following forced abstinence, female mice had significantly increased SST activity in their prefrontal cortex but significantly reduced SST activity in the BNST.

Crowley said the researchers plan to examine whether the changes in SST activity directly contribute to the reductions in overall neural activity in the female mice forced to abstain from alcohol or whether these changes are a response to the overall changes in neural activity.

Understanding the role of SST neurons in response to alcohol withdrawal could one day lead to new treatments for alcohol use disorder. One promising aspect of drug development is that somatostatin-modulating drugs are already marketed in the treatment of some cancers, so they might be repurposed to target neural pathways, Crowley noted.

This study was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the Penn State Social Science Research Institute. ■

“Forced Abstinence From Alcohol Induces Sex-Specific Depression-Like Behavioral and Neural Adaptations in Somatostatin Neurons in Cortical and Amygdalar Regions” is posted

here.