In the early years of the eugenics movement in the United States, Samuel E. Smith delivered his presidential address at APA’s 71st Annual Meeting in May 1915. He advocated for APA members to encourage the educated population to support sterilization as a means to prevent new cases of mental illness and mental retardation:

Responsibility rests upon us for the guidance of an awakened public, better informed and more intelligent than ever before, in the difficult field of prevention. … If this strong group [the middle class] can be brought to a fine appreciation and consistent support of the movement now being inaugurated throughout the land for the thorough medical examination of the school children and the treatment and training of the large group of subnormals amenable to such management, the certain penalty of procreation by them and the value of sterilization as a means of prevention, something positive will be accomplished. This support is obtainable, if sought, and there is no higher duty resting upon us as members of this Association than to seek it.

Smith included the insane in his argument, indicating that the method of “segregation”—that is, putting all the insane in large asylums—had been unsuccessful and was becoming too great a financial burden. In that same year, A. J. Rosanoff broadened the issue to immigrants:

The rate at which the population of foreign birth or parentage is increasing… is greater than that of the native population. … [S]hould such conditions continue to prevail, the racial composition of the population will gradually change and eventually become more or less like that of the “new immigration”; the prevailing elements, instead of being Dutch, English, Scotch, German, Irish and Scandinavian, will be Italian, Slavonic and Hebrew.

In July 1924, the American Journal of Psychiatry published an article by Lewellys F. Barker “denigrating”* Black people while expressing concern about immigrants: “[H]ow many have fully considered the meaning of the report that of the immigrants that we have admitted to this country in a period corresponding to a single generation, no less than two million were of an intelligence lower than that of the average negro?”

In the same year, an article in the journal indicated that the annual cost to the American people for the care and treatment of people with mental illness and the maintenance of criminals and feebleminded individuals was “appalling.”

Smith and the many other psychiatrists in the decades to come who supported eugenics were hardly alone. (Eugenics is broadly defined as the intention to improve the human species through breeding desired traits and sterilization to contain undesired traits). Illustrious figures who were eugenics supporters include Alexander Graham Bell, W. E. B. Dubois, Helen Keller, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (of Corn Flakes fame), Theodore Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Sanger, and Winston Churchill. In 1910, more than a generation before Churchill would fight Hitler and his genocide plan, Churchill warned:

The unnatural and increasingly rapid growth of the feeble-minded and insane classes, coupled as it is with a steady restriction among the thrifty, energetic, and superior stocks, constitutes a national and race danger which it is impossible to exaggerate. … I feel that the source from which the stream of madness is fed should be cut off and sealed up before another year has passed.

Sterilizations Carried Out at State Hospitals, Schools

The type of sentiments expressed by Churchill and Smith were the foundation of eugenics in the United States, a movement that accounted for over 60,000 sterilizations.

The aspects of eugenics that separates out physicians—and often they were psychiatrists—from the eugenics enthusiasts is that physicians oversaw the sterilization procedures. Sterilizations were generally carried out at state hospitals and state schools for the “feebleminded.” If certain groups were targeted for sterilization in a facility, the physician superintendent would certainly have known.

Thirty-three states in the United States passed laws permitting forced sterilization. The first serious attempt in the United States to use forced sterilization for eugenic purposes occurred in 1849, when Gordon Lincecum, a Texas physician, proposed a bill mandating the eugenic sterilization of mentally handicapped people and others whose genes he deemed undesirable. The proposal never became law. The first state to introduce a compulsory sterilization bill was in 1897, but the proposed law failed to pass. Eight years later, Pennsylvania’s state legislators passed a sterilization bill that the governor vetoed. Indiana became the first state to enact sterilization legislation in 1907.

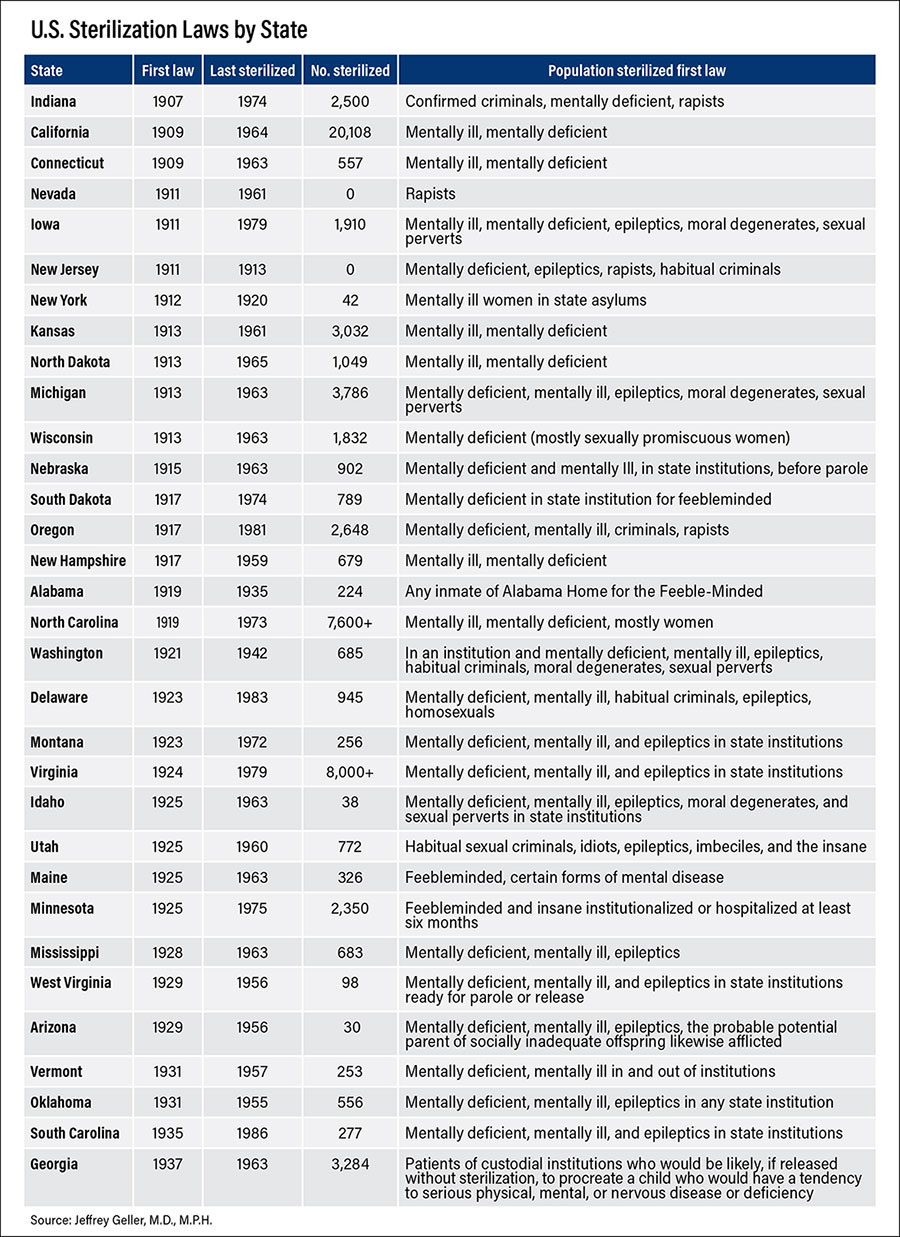

Table 1 shows the states, the date of the state’s first sterilization law, the date of the last sterilization, the official number of people sterilized, and the target population of the first law. For states that had a law but never sterilized anyone, the later date is the date the law was repealed. But the actual practices were not that simple. States passed multiple laws in succession, sterilized people before there was a law (for example, Kansas), sterilized people even though the state never had a sterilization law (for example, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania), kept sterilization laws on the books for two or more decades after they stopped sterilizations, kept poor records, and manipulated records. The official count of the number of sterilizations that were performed is only the minimum number; no one knows the actual count. And no state ever named Blacks in their target population, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t targeted.

While the states were individually addressing eugenics, the federal government weighed in early on. Harry Laughlin, director of the Eugenics Research Office, proposed a federal mandatory sterilization law. It went nowhere. Nonetheless, the U.S. Supreme Court, in considering Virginia’s sterilization law in Buck v. Bell, ruled 8-1 on May 2, 1927, that laws mandating the sterilization of “mentally handicapped” individuals did not violate the Constitution. In the majority opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, he made it clear that he supported sterilization: “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

Carrie Buck was a resident of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, as was her mother. She had a daughter also labeled feebleminded. It was these three females that led Holmes to conclude his opinion with the famous statement: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” This decision became the springboard for states to ramp up the number of sterilizations that were performed. But it did something even more nefarious: It allowed states to pay less attention to ensuring that those they sterilized met the state’s own criteria for sterilization. This is so because neither Carrie Buck nor her daughter (who resulted from Carrie Buck’s being raped by a nephew of her adoptive mother) was developmentally disabled. (As a footnote in history, the chief justice of the United States in the case was former President William H. Taft.) This decision, although not intending to, opened the door for some states to focus on the sterilization of Black people. It did not matter that Carrie Buck and her family were white; it mattered that their sterilization was the result of chicanery.

Racist Eugenics in the States

North Carolina, which has the third highest number of sterilizations among the states, was the most racist in its application of eugenic policies. Blacks represented 39% of those sterilized overall; by the later 1960s, they made up 60% of those sterilized, even though they made up only 25% of the population.

Black people were targeted not only because of the color of their skin but also because they represented an increasing percentage of those on welfare—31% in 1950 and 48% in 1961. Targeting welfare recipients would decrease the financial burden on the state. Further, 77% of those sterilized were women, and about half were under 20 years old. Black women were thought to have higher fertility rates than their white counterparts and were more likely to be on welfare. They also were thought to be more likely to have illegitimate children, in part because Black women were presumed to have uncontrollable sexual behavior. Thus, controlling reproduction was best accomplished through sterilization. Black teenage girls were sterilized without being informed what was happening to them. They learned years later they could not conceive when they tried to have a child with their husbands. Girls who weren’t even in their teens yet were sterilized after the occurrence of incest.

In South Carolina, Black individuals were also singled out; the number of sterilizations performed on Black people was disproportionately higher than their numbers in the state facilities where the patients came from. Black women who sought a doctor to deliver their children usually had to agree to sterilization as a condition for the doctor’s assistance. By the time sterilization ended in South Carolina, in 1963, all of the 23 procedures that year were performed on Black women.

In Virginia, through a good part of the eugenics period, Blacks were not a target of sterilization. Twenty-two percent of those sterilized were Black, which was roughly proportionate to their presence in the state. That did not reflect the absence of prejudice, however. On the same day that Virginia passed the Sterilization Act, the commonwealth passed the Racial Integrity Act. This legislation made it unlawful for a white person to marry a person who was not white. A white person was defined as a person “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.”

After Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, the number of racist sterilizations performed in Virginia escalated as part of Sen. Harry F. Byrd Jr.’s “massive resistance” campaign against school integration; the theory was that having fewer Blacks in the state would make school integration harder to achieve. Racist sterilizations were considered again in the early 1960s when the commonwealth proposed punitive sterilization of welfare mothers with illegitimate children. The Black population was expanding more rapidly than the white population, and the state wanted to end that expansion.

Georgia, in contrast, did not target Blacks. Georgia stayed focused on younger individuals who were mentally or physically disabled and in state institutions. Most people in state facilities were white, as noted above. Mississippi’s experience was similar to Georgia’s, but prejudice and discrimination were evidenced by the inability of state facilities to admit Black people with developmental disabilities; that didn’t happen until 1963. While Alabama also did not target Blacks, racism was nonetheless a distinct factor: The sterilization of Black people would not better the race—as it would for white people—as the Black race was thought to be simply beyond any hope of improvement.

The issue of racist application of eugenics was not limited to Southern states. Of California’s 20,000+ sterilizations (one-third of all sterilizations done in this country), 4% were performed on Black individuals, yet they made up only 1% of the population. These numbers are probably lower than the actual numbers as evidence indicates that California altered or destroyed some records. Michigan’s records are also questionable. As best as can be ascertained, in Michigan a Black person may have had a four times greater chance of being sterilized than a white person. Michigan also had a practice of “setting aside” deformed newborns, who died without the attention they needed. Whether this was done disproportionately with Black infants is not known due to inadequate records, almost assuredly intentionally manipulated. Oklahoma has no information on the sterilization of Black people, but it appears there was widespread sterilization of Native American women in the 1970s, and no records were kept—these women are not counted in the state’s total. Native Americans were also a targeted population in Vermont.

Federal sterilization efforts often had racist intent. An example occurred during the Nixon administration. In 1970 there was a very significant increase in Medicaid-funded sterilization, which was voluntary as a matter of policy but may have been involuntary as a matter of practice. Women were misinformed or not informed about the purpose of the surgery they were about to undergo. The primary target of this program was women of color.

On a nongovernment national level, the most outstanding example is Margaret Sanger and the “Negro Project.” Some see Sanger, the founder of what became Planned Parenthood, as manipulative and evil with a eugenics plan for Black people. Others see her as a well-meaning person whose original “beneficent” plan was never carried out. This year Planned Parenthood disavowed Sanger for her eugenic views.

Should APA disavow its prominent eugenics supporters? One of these is an American psychiatry icon: Adolf Meyer. Are we ready to start taking down his statues and portraits? ■

*I used the word “denigrating” intentionally, but it should generally not be used as it is a racist word that comes from the same root as negro.

“Presidential Address. On the Relation of Psychiatry to the State” is posted

here.

“Some Neglected Phases of Immigration in Relation to Insanity” is posted

here.

“Psychiatry and Public Health” is posted

here.