Ever since Russian psychiatrist Alexander Rosenblum showed that inducing high fevers in patients could reduce their symptoms of psychosis nearly 150 years ago, psychiatry has been interested in the potential connection between infectious disease, the immune system, and psychotic disorders.

Years later, scientists uncovered that the patients cured by Rosenblum and subsequent practitioners of pyrotherapy likely had syphilis-induced psychosis. Over the decades since the syphilis bacterium was discovered, researchers have identified several other agents with psychosis-inducing potential, including the parasites that cause malaria and toxoplasmosis. More recently, researchers have discovered that in some cases, the body’s own antibodies can trigger a rare neurological disorder known as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Unknown in scientific literature 15 years ago, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is now recognized as the most common cause behind autoimmune psychosis.

Portrait of Disease Emerges

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis was first identified by a team led by Josep Dalmau, M.D., Ph.D., a senior investigator at the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Barcelona, after reviewing the cases of four young women who presented with delusions and hallucinations coupled with abnormal movements and seizures. These women were later determined to all have ovarian tumors.

Dalmau, who is also an adjunct professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, discovered that the cause of these women’s neurologic and psychiatric symptoms was an antibody attacking the NMDA receptor, which binds the neurotransmitter glutamate.

Since that initial discovery (which was published in a 2008 article in Lancet), Dalmau’s group has studied nearly 600 patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and developed a portrait of this disorder. The disease evolves in stages, with psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, insomnia, mania, and/or memory deficits, typically emerging first. Neurological problems, such as abnormal movement and seizures, manifest about one month after that, at which point patients deteriorate to the point of needing intensive care.

As was seen in the initial four women studied, tumors can contribute to the development of autoantibodies that attack the NMDA receptor. Viruses have also been implicated in many cases, particularly those such as herpes viruses, which can hide dormant in the human body. Some recent patient case reports also indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may induce at least brief psychotic symptoms, though whether this is caused by activity at the NMDA receptors remains unclear. Additional studies have found that patients with antibodies attacking other neuronal receptors also exhibit similar symptoms as patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Early Identification Key

Although anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is rare (estimated to affect one to two per million people), early identification of the disorder is key to the prevention of the emergence of severe neurological problems such as catatonia.

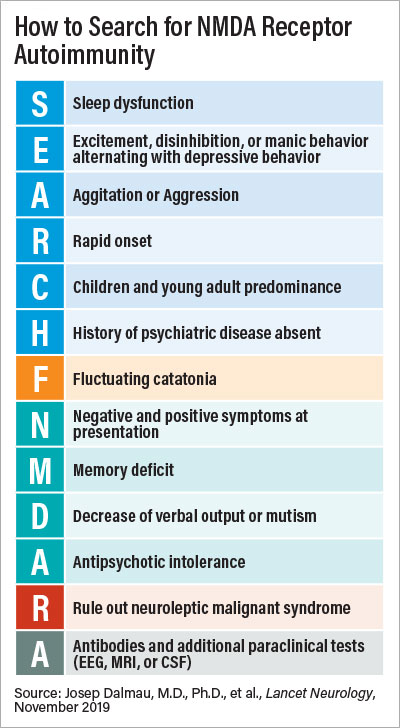

Analyses conducted by multiple clinical groups have identified several “red flags” that might point to an autoimmune problem in a patient with psychosis (see box). Patients without a family history of psychosis who develop symptoms quickly, especially if they are accompanied by agitation, abnormal speech, or other cognitive problems, may be potential candidates for autoimmune psychosis.

Recently, Dalmau’s team showed that certain aspects of cognitive dysfunction might help differentiate first-episode psychosis versus anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. “Autoimmune-affected patients tend to have less dysfunction in serial dependence compared with people with schizophrenia,” he said. (Serial dependence is a component of visual memory that lets the brain store certain visual cues for quick retrieval.)

If a psychosis patient is suspected of having autoimmune antibodies, an MRI scan or lumbar puncture (to collect spinal fluid) can identify whether there is any brain inflammation.

There are effective treatments for the disorder, Dalmau told Psychiatric News. The common treatment of the disorder involves steroid therapy coupled with plasma transfusions; if a tumor is identified, it is removed. Recovery can be slow, with patients continuing to experience residual memory or motor problems for months, Dalmau noted. “But once recovered, patients have a good prognosis, with less than 10% experiencing any symptom relapse,” he said.

Diagnosis can be more complicated if the patient never shows neurological issues associated with the disorder and remains in an extended state of “autoimmune psychosis”—a disorder popularized by the 2012 book (and subsequent film adaption) Brain on Fire. Studies estimate about 5% of patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis fall into this category.

Thomas Pollak, Ph.D., M.R.C.P.sych., a psychiatrist and clinical lecturer at King’s College London, told Psychiatric News that Brain on Fire helped spread broader awareness of autoimmune psychosis.

“On the patient end, there remains a lot of stigma about schizophrenia, so hearing that psychotic symptoms might be due to harmful antibodies is a preferred scenario,” he said. But he has encountered patients who believe so deeply that they have an autoimmune problem—despite little clinical evidence—that they refuse to discuss conventional treatment with antipsychotics.

Similarly, “after the book came out, many doctors began to wonder how many schizophrenia inpatients could improve if they got some immune therapy,” Pollak said.

The current molecular data support the notion that autoimmune psychosis is a rare subtype of psychotic disorder. Numerous groups have conducted assays to quantify the presence of neuronal autoantibodies in patients with schizophrenia or controls with no psychosis. Estimates of the percentage of people with schizophrenia and anti-NMDA receptor or related autoantibodies range from 0% to 19%, depending on the type of lab test administered. These percentages are similar in people who do not have schizophrenia.

“These antibodies are generally not causal, but they still may have value as biomarkers for disease progression,” Pollak said. He recently published a study that showed adults considered at high risk of psychosis who had anti-NMDA receptor antibodies performed worse on cognitive tests than high-risk adults without antibodies. ■