Imagine a schizophrenia medication that was nearly as effective as clozapine but did not increase a patient’s risk of white blood cell depletion. Imagine if this powerful but well-tolerated drug might also improve some of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as social withdrawal.

Such a medication might seem fanciful, but amisulpride, an antipsychotic with all these characteristics, already exists.

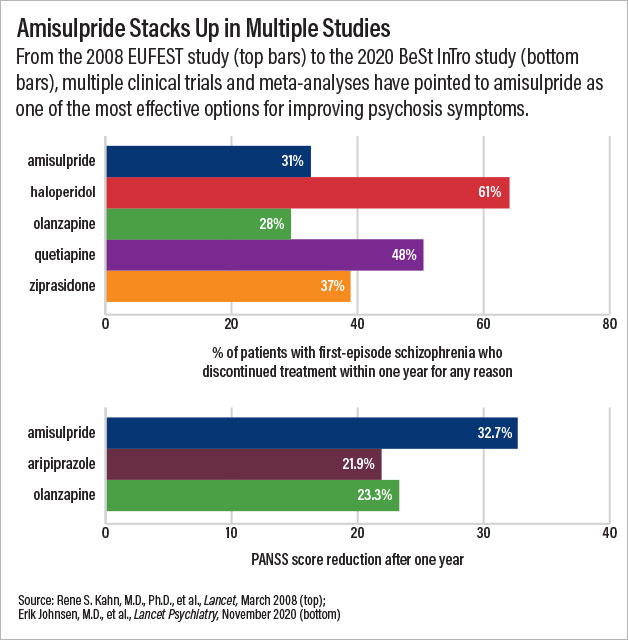

A clinical trial published in Lancet Psychiatry last November illustrates the potential of amisulpride. Investigators in Norway and Austria randomized 144 adults with recently diagnosed schizophrenia to receive amisulpride, olanzapine, or aripiprazole for one year. By the end of the study, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores of patients in the amisulpride group had fallen by nearly 33 points—a decrease of about 10 points more than seen in patients receiving either of the other two medications.

Stephen Marder, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Psychiatric News that a 10-point difference on the PANSS is clinically meaningful. “The advantages of amisulpride were substantial; these are significant improvements that a clinician would notice quickly,” said Marder, who was not involved in the study.

Unfortunately, though amisulpride is approved in numerous countries across the globe, the United States is not one of them. And Marder noted that since the patent on amisulpride expired in 2008, it is unlikely to ever gain approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); there is little financial incentive for companies to sponsor the necessary clinical testing for a generic medicine.

A chemically modified form of amisulpride would be considered a new drug with patent protection, however. A small startup known as LB Pharmaceuticals is working to develop such a compound to bring this potentially valuable therapy to U.S. shores.

Without FDA Approval

Vincent Grattan, R.Ph., cofounder of LB Pharmaceuticals, first became interested in amisulpride about 15 years ago when he was a clinical pharmacist overseeing the medication management for inmates in several U.S. prisons. “As many are aware, correctional facilities are de facto mental health hospitals, and I wanted to make sure we were stocking the most reliable medications,” he said.

Grattan came across a large British study known as the Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1), which compared the long-term effectiveness of older first-generation antipsychotics with newer second-generation antipsychotics.

“I figured the newer medications would come out on top, but the results showed first-generation antipsychotics performed better,” he said. “And the driving force seemed to be a first-generation antipsychotic I had never heard of called sulpride.”

Though sulpride was already a generic (and thus unlikely to be approved in the United States), there was a newer analog of sulpride called amisulpride that also showed strong efficacy in several European studies. Grattan was hopeful that this newer compound, which still had patent protection, would find its way to the United States.

In fact, the French company Sanofi, which manufactured amisulpride, submitted a new drug application to the FDA in 1998, but the company later withdrew this application. Though the official company statement did not provide details, LB Co-founder and CEO Zachary Prensky said he believes the impetus was financial. “The patent was expiring in a few years, and the leadership calculated the cost and time required to complete all the required trials would not be profitable,” he said.

Benefits of Amisulpride

Amisulpride, a sulfur-containing benzamide, has an unusual property in that at lower doses (100 mg to 300 mg a day), it tends to stimulate rather than block dopamine release, producing antidepressant effects. Clinical studies in the late 1990s supported this idea, showing that low-dose amisulpride was more effective in treating schizophrenia patients who predominantly had negative symptoms (for example, low energy and mood) than those experiencing psychotic symptoms. At the standard dose of 400 mg to 800 mg a day, amisulpride does not seem to have any direct effects on negative symptoms.

Over the next several years, more data emerged demonstrating the potential benefits of amisulpride. Studies found that amisulpride could be safely given at an optimal dose right away (antipsychotic dosing usually involves increasing the levels over a couple weeks). This trait made amisulpride a preferred option for managing acute psychosis. Other studies suggested that amisulpride was the best add-on agent for patients with severe schizophrenia who failed to respond to clozapine.

In 2005, a large clinical study conducted across 13 countries known as EUFEST set out to compare the effectiveness of five antipsychotic medications for first-episode psychosis. Rene Kahn, M.D., Ph.D., the Esther and Joseph Klingenstein Professor and System Chair of Psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, was working in the Netherlands at the time.

“I heard anecdotal reports that it [amisulpride] was well liked by patients, but I came into the EUFEST trial with no biases about amisulpride,” said Kahn.

The results of that study, published in 2008, changed his views. Alongside olanzapine, amisulpride had the lowest rates of discontinuation for any reason across an entire year. A few years later, Kahn led another clinical study known as OPTiMiSE, which found that 56% of people with schizophrenia achieved remission of their symptoms after just four weeks of amisulpride treatment.

Kahn noted that amisulpride is not risk free; it can significantly elevate production of the hormone prolactin, which causes symptoms such as loss of libido or abnormal breast growth in men. However, amisulpride is less likely to lead to chronic health problems such as obesity or cardiovascular disease, known risks associated with other second-generation antipsychotics.

“It’s also an older drug that is dirt cheap, so I can see the appeal in the countries where it is used,” Kahn added.

A comprehensive meta-analysis published in 2019 in JAMA that compared 32 oral antipsychotics helped solidify the sentiments shared by Kahn and other investigators who have conducted clinical studies with amisulpride. That meta-analysis identified amisulpride as the second most effective antipsychotic at reducing overall symptoms in schizophrenia patients (behind clozapine) and the most effective in terms of reducing positive symptoms. The analysis also ranked amisulpride better than clozapine in terms of tolerability and side effects.

Modified Amisulpride Being Studied

In 2014, Grattan and Prensky connected to discuss ideas for how to bring amisulpride to the United States. Their initial thought was to designate amisulpride as an orphan drug for ultra-resistant schizophrenia, given its ability to augment clozapine. (An orphan drug designation provides benefits like tax incentives for groups willing to sponsor a treatment for a rare disorder.)

That idea did not pan out, but working with chemist Andrew Vaino, Ph.D., chief science officer for LB, the pair devised a strategy for chemically enhancing the amisulpride molecule, and LB was born.

“One shortcoming of amisulpride is that the molecule does not get into the brain that easily,” Prensky said, which necessitates oral doses as high as 800 mg a day. (As a comparison, the typical doses for the commonly used antipsychotics olanzapine or risperidone are about 6 mg to 20 mg a day.)

Adding a small chemical tag to amisulpride to make it more fat soluble would enable it to pass the blood-brain barrier more easily, allowing doses of the medication (and potential side effects from these doses) to be reduced.

LB recently completed its phase 1a safety study of its methylated amisulpride (named LB-102) in healthy volunteers and found that the drug was well tolerated up to 150 mg a day. This is well above the effective dose for most patients, which is believed to be between 25 mg to 75 mg a day based on an ongoing PET scan study looking at how the drug binds to brain receptors. Prensky said LB is preparing to launch its phase 2 study this year and hopes to recruit at least 300 participants with schizophrenia.

“It’s still early in the process, but we are hop-skipping along nicely,” Prensky said. He pointed out that the FDA approved an intravenous formulation of amisulpride in 2020 to treat post-operative nausea and vomiting. That medication only uses 5 mg of amisulpride, but Prensky said the approval did provide some guideposts as to what concerns the FDA has in relation to amisulpride.

“In addition, we have also gotten some of the top schizophrenia scientists in the country on our scientific board to point us in the right direction,” he added. “When luminaries like John Kane, Cristoph Correll, and Ira Glick were willing to join us in the earliest days, it shows that the psychiatric community wants this drug in the United States.” ■

“Amisulpride, Aripiprazole, and Olanzapine in Patients With Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders (BeSt InTro): A Pragmatic, Rater-Blind, Semi-Randomised Trial” is posted

here.

“Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect on Quality of Life of Second- vs First-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1)” is posted

here.

“Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in First-Episode Schizophrenia and Schizophreniform Disorder: An Open Randomised Clinical Trial” is posted

here.