Intravenous ketamine may be safe and effective in adolescents with treatment-resistant depression, according to a small study in the American Journal of Psychiatry. As previously demonstrated in adults, a single ketamine infusion dramatically reduced depressive symptoms in adolescents after 24 hours relative to those who received a control infusion. These improvements lasted for at least two weeks.

“Treatment-resistant depression is debilitating for anyone, but it can be especially damaging during the teenage years,” said lead study author Jennifer Dwyer, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of child psychiatry at Yale University and co-director and co-founder of Yale’s Pediatric Depression Clinic. “So many important aspects of teenage development rely on the ability to socialize and get out in the world. We need additional safe and effective options for adolescents who don’t respond to first-line therapies.”

Dwyer and colleagues enrolled 17 adolescents aged 13 to 17 years with treatment-resistant depression in a four-week crossover trial. (The participants had failed an average of 3.24 prior treatments, and the average length of their current depressive episode was 21 months.) They were randomized to receive a single infusion of either ketamine (0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg over 40 minutes), followed by an infusion of the other compound two weeks later. Midazolam was chosen as the comparator since it is an anesthetic that has similar properties to ketamine but is not expected to produce antidepressant effects. The participants remained on their current medication(s) while participating in the study. The youth were evaluated using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) for several days after each infusion.

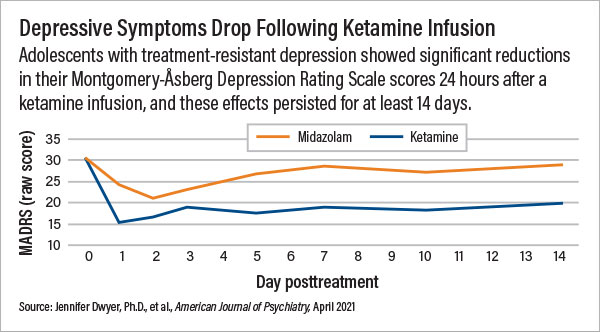

The adolescents in the ketamine reported significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms after 24 hours compared with those who received midazolam; average MADRS scores dropped from 30.56 to 15.44 in the ketamine group and from 31.88 to 24.13 in the midazolam group. Overall, 76% of the adolescents who received ketamine achieved a treatment response (defined as a >50% reduction in MADRS scores) within three days, compared with 35% of participants who received midazolam. MADRS scores continued to remain lower in the ketamine group compared with the midazolam group 14 days post-infusion.

The adolescents who received ketamine experienced more dissociative symptoms as well as greater increases in blood pressure and heart rate following the infusion compared with adolescents who received midazolam. While these symptoms went away within a couple of hours, the authors cautioned that these differences may have led to certain expectations of the participants, which may have impacted the results.

“We were encouraged to see the separation between ketamine and midazolam for the full two weeks,” Dwyer said, noting that ketamine trials in adults have typically found that antidepressant benefits after a single infusion start to dissipate between a week to ten days.

Research suggests ketamine works in part by stimulating synaptic plasticity—encouraging neurons to form new connections with each other. Dwyer explained that the enhanced plasticity potential in younger brains compared with adults could allow for longer durations of ketamine-associated antidepressant effects. Her team is working on a trial in adolescents looking at how long the antidepressant effects of a conservative ketamine paradigm (six infusions over three weeks) may last in adolescents.

“The fact that ketamine brings about noticeable improvements in mood within one day is why ketamine is so exciting for the field,” said Kathryn Cullen, M.D., chief of the Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “However, this study is just an important first step toward establishing ketamine as clinically useful for adolescents.”

Cullen, who has also studied the effectiveness of ketamine in adolescents with treatment-resistant depression, noted that researchers do not yet know whether ketamine can sustain long-term remission of depression. She also cautioned that ketamine will not be a solution for every adolescent.

“We have to remember to look at the whole person and appreciate their particular situation,” she said. “If a child is depressed due to an abusive environment, then no single pill or infusion will solve the problem; we need comprehensive strategies.”

This study was supported by a Ritvo Pilot Grant from Yale University, an American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Pilot Award, and a Thrasher Pediatric Research Fund Early Career Award. ■

“Efficacy of Intravenous Ketamine in Adolescent Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Midazolam-Controlled Trial” is posted

here.