People with schizophrenia often experience problems with learning, memory, attention, and social cognition. The underlying reasons for these cognitive problems vary, but one cause may be related to the psychotropics commonly prescribed for the disorder—particularly those that target the neurotransmitter acetylcholine called anticholinergics.

A study published in AJP in Advance has now quantified the cumulative effects of anticholinergic medications on cognition in people with schizophrenia. Such information may help guide physicians as they consider the risks and benefits when prescribing.

“Psychotropic medications, especially antipsychotics, are critically important therapeutics for schizophrenia, have substantially improved the lives and outcomes for countless patients living with schizophrenia, and represent an essential staple of comprehensive treatment,” wrote lead study author Yash Joshi, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues. Nonetheless, physicians treating patients with schizophrenia should be aware that there may be trade-offs when treating patients with medications with significant anticholinergic properties, the authors noted.

Joshi and colleagues analyzed medication records of 1,120 adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were part of a large genetics study called the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia-2 (ACOG-2). They calculated an Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) score for each patient based on medication profile. Individual medications received a score of 0 to 3 based on their anticholinergic strength (clozapine and olanzapine received 3s, for example, whereas risperidone received a 1), and were added together to create a patient’s total ACB score. Most scores were available on an existing database developed by researchers at the University of Indiana. The researchers estimated scores for other medications based on their similarities to medications with known ACB scores.

The average ACB score for the sample was 3.8, with individual patient scores ranging from 0 to 20. Antipsychotics contributed to the most anticholinergic burden among the study cohort, followed by medications used to treat antipsychotic-induced motor problems such as tremors.

“For context, an ACB score of 3 in healthy older adults is associated with cognitive dysfunction and a 50% increase in risk for developing dementia,” the authors wrote. “In our data, the proportion of patients with an ACB score of at least 3 was 63%, with approximately 25% having an ACB score ≥6.” Only 7% of the participants had an ACB score of 0.

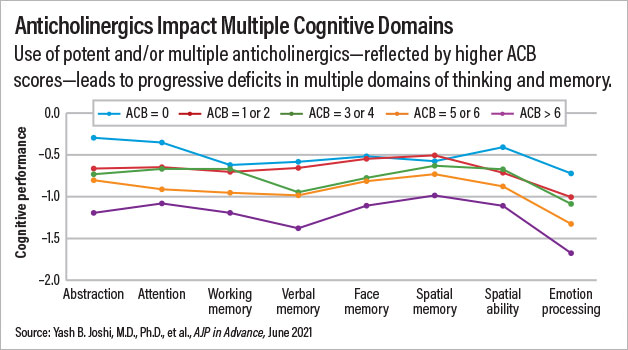

The participants were grouped into five categories based on their ACB scores: no anticholinergic burden (ACB score=0), low anticholinergic burden (ACB score=1 or 2), moderate anticholinergic burden (ACB score=3 or 4), high anticholinergic burden (ACB score=5 or 6), or very high anticholinergic burden (ACB score=above 6). Joshi and colleagues found a direct correlation between higher ACB scores and worse cognitive performance in 16 of the 17 cognitive tests given to ACOG-2 participants. For example, global scores on the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery among patients with no, low, average, high, and very high anticholinergic burden were 0.51, 0.70, 0.85, 0.96, and 1.15 points below the adult average, respectively.

The deficits were similar across a range of cognitive domains, including attention, verbal memory, and emotional processing, Joshi noted.

The research team did extensive statistical analyses and found anticholinergic burden impacted these various processes roughly equally. “It wasn’t a case that the medicines primarily impacted one or two core features of cognition that cascaded and indirectly impacted other processes,” Joshi explained. The connection between higher ACB score and worse cognitive function persisted even after adjusting for patients’ age, severity of illness, duration of illness, smoking status, and antipsychotic dose.

“No physician is actively looking to impose a high anticholinergic burden on their patients, but I think these findings highlight what can happen when we focus on specific symptoms in the here and now,” Joshi said. “And when a patient develops acute symptoms and is in crisis, that is the right mindset. But for chronic care, physicians should routinely ask whether their patients need every medicine in their regimen.”

That includes nonpsychotropic medications as well, noted Jeffrey Bishop, Pharm.D., an associate professor of experimental and clinical pharmacology who specializes in the cognitive side effects of drugs. “General medications like antihistamines are also strong anticholinergics,” he said. “We pay a lot of attention to how different drug classes interact in the elderly; this study reinforces that patients with schizophrenia may also be sensitive to anticholinergic effects.”

Bishop noted that he led a study in 2017 that found an association between high anticholinergic burden and cognitive impairment in patients with psychotic disorders, though the effects were more pronounced in patients with schizophrenia compared with those with schizoaffective disorders or psychotic bipolar disorder.

This study was supported by multiple grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, along with support from the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation; the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; the VISN-22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and Department of Veterans Affairs. ■

“Anticholinergic Medication Burden–Associated Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia” is posted

here.

“Cognitive Burden of Anticholinergic Medications in Psychotic Disorders” is posted

here.