“I just feel like I am broken. I am the worst pregnant woman ever.”

These are the words of a woman interviewed by Aleksandra Staneva, Ph.D., and colleagues as they conducted a study on how women experience and interpret psychological distress while they are pregnant. The study was reported in the June 2017 Health Care for Women International. What they learned is that for many women, experiencing distress during pregnancy runs smack into unrealistic cultural expectations and fuels excessive guilt. Women report feeling totally responsible for the well-being of their babies. With increasing media attention to the harmful effects of stress on fetuses, some women believe they are supposed to remain happy and serene throughout their pregnancies, and if they don’t, it’s their fault. So what does research to date actually tell us about the effect of maternal antenatal distress on offspring?

First, a word about the term “distress.” In the context of research on the effects of antenatal maternal psychological states on offspring, “distress” encompasses maternal anxiety, depression, and perceived stress. This is because studies to date have found that any of these, or any mixture of these, has similar effects on offspring. Though there are some distinctions, most researchers have found it more valuable to examine these collectively.

Distress During Pregnancy: A Case Example

Delia* is a 28-year-old woman with recurrent major depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) stemming from prolonged childhood emotional, physical, and sexual trauma. She is raising her 2-year-old daughter, Keisha, on her own with limited financial resources and housing insecurity. While pregnant with Keisha, she was highly stressed and severely depressed. Being pregnant made her feel vulnerable and intensified her PTSD symptoms. She had previously responded well to sertraline but discontinued it because she thought she shouldn’t take medication while pregnant. Her pregnancy was complicated by preeclampsia, which was frightening. Keisha was born a month early; she was a healthy baby but fussy. As a toddler, she is sensitive and reacts with fear to new situations.

Delia has just learned she is pregnant again. Recalling how difficult her last pregnancy was and how that may have affected Keisha, she sees a psychiatrist, Dr. Wilkins, for ideas about how to maintain mental health.

To provide context for how a psychiatrist can help, we’ll review some relevant information.

Homeostasis, Allostasis, and Allostatic Load

As a prelude to understanding the effects of distress during pregnancy, it helps to understand how bodies handle stress in general. Certain body systems need to be maintained within narrow ranges to operate effectively. Blood pH and body temperature are examples. Processes that maintain these systems within range are known as homeostasis. Stress can disturb homeostasis. To counter threats to homeostasis, our bodies mobilize the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the sympathetic nervous system, and the immune system. That mobilization is known as allostasis. For example, the sympathetic nervous system prepares the body for fight or flight by activating the heart, blood vessels, and muscles, and the immune system prepares to respond to possible wounds or infection. Mobilizing these responses intermittently enhances health. Exercise is an example of healthy allostasis. As with intermittent physical challenges, intermittent cognitive and/or emotional challenges can promote health. On an emotional level, insufficient challenge can lead to boredom, an affective state that can drive a person to seek new goals and positive stimulation.

By contrast, when allostatic processes are repeatedly and chronically mobilized, we pay a price. The resultant wear and tear are known as allostatic load. High allostatic load includes physiologic dysregulation of multiple body systems that contributes to disease.

Pregnancy is itself a physiologic stressor. It is sometimes referred to as a natural stress test, bringing out vulnerabilities to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and other conditions. Adding psychological stress, trauma, and/or chronic societal strains such as economic deprivation and racism can lead to substantial allostatic load during pregnancy. This can influence the likelihood of adverse pregnancy outcomes and can influence fetal development.

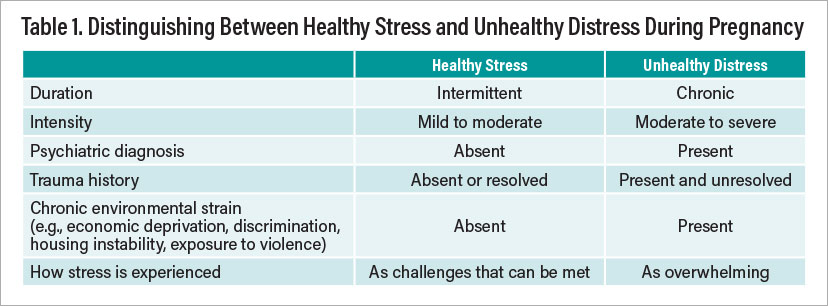

Just as different patterns of stress can be healthy or unhealthy for people in general, research to date suggests that different patterns of antenatal stress can either promote or impede healthy fetal development.

Healthy Stress During Pregnancy

How can researchers know how fetuses react when their mothers are stressed? One particularly helpful clue is how the fetal heart rate changes in response to maternal stress. To restore homeostasis under stress, it’s important for some parameters to vary flexibly (for example, heart rate) to keep others (for example, blood pressure) constant. For this reason, beat-to-beat variability of the fetal heart rate is an indicator of health. When a pregnant woman experiences mild to moderate intermittent stress, her fetus responds with a temporary increase in heart rate variability. That response to maternal stress intensifies as the fetus matures, and it becomes increasingly well coupled with fetal movement. These changes suggest that the fetus is becoming more adept at normal allostasis, which may promote healthy development later in life. Research by Janet DiPietro, Ph.D., published in the August 2012 Journal of Adolescent Health shows that newborns who were exposed to mild to moderate intermittent maternal distress in utero have faster neural conduction, consistent with the hypothesis that exposure to healthy stress in utero advanced their neural development. Similarly, toddlers who were exposed to mild to moderate intermittent maternal distress in utero show more advanced motor and cognitive development.

Unhealthy Stress During Pregnancy

By contrast to the salutary effects of intermittent mild to moderate maternal stress on fetal development, severe and/or chronic maternal distress is associated with higher risks for adverse perinatal outcomes and long-term adverse effects on offspring. The difference can be detected in utero. Fetuses of pregnant women who have high anxiety tend to have heart rates that are more reactive to acute stressors. The fetuses of pregnant women with low socioeconomic status tend to have reduced beat-to-beat variability.

When maternal distress reaches the level of a clinically diagnosable disorder that remains untreated, long-term adverse effects can ensue. For example, untreated antenatal major depression is associated with increased risk of premature birth and low birth weight. Infants and toddlers exposed to maternal depression in utero show excessive crying; reduced motor and language development; and more distress, fear, and shyness than offspring not exposed to maternal depression. Children and adolescents exposed to antenatal maternal depression have an increased risk of emotional, behavioral, and cognitive problems.

Epigenetics and Fetal Programming

There is increasing evidence that intrauterine environmental exposures can “program” a fetus to develop in a certain way. It is posited that this programming confers the evolutionary advantage of using intrauterine cues to predict what awaits in the outside world and to develop accordingly. An example is that when women are pregnant during famines, their offspring have a higher likelihood of being overweight and experiencing reduced glucose tolerance later in life. It is hypothesized that the famine-exposed fetuses developed a “thrifty phenotype” to adapt to a resource-poor environment. Health problems ensue when there is a mismatch between the intrauterine environment and the external world—for example, when an individual who has developed a slow metabolism in response to in utero nutritional deprivation grows up in an environment replete with food.

There is evidence that fetal programming also occurs in response to maternal psychological distress. If a fetus will be born into a world filled with constant dangers, it might be adaptive to develop a highly reactive stress response system. This appears to be what happens to offspring of women who experience prolonged, clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression, and stress while pregnant. In babies, exposure to substantial maternal distress in the womb is associated with increased physiologic and behavioral reactivity to stress, such as a routine heel stick at birth. Over time, the offspring’s hyper-responsive physiologic responses can contribute to poor health.

Fetal programming is thought to occur via epigenetic pathways—environmental factors triggering molecular processes that change the expression of fetal or placental genes. A major caution regarding fetal programming research is that it is difficult to tease out the effects of the in utero environment from other influences. Studies have examined newborn stress reactivity, brain connectivity, and temperament to separate in utero from environmental influences after birth. For example, newborns of women who had untreated antenatal depression show reduced connectivity between their prefrontal cortex and amygdala. This is associated with increased heart rate reactivity when they were fetuses.

What’s especially difficult to disentangle are shared genetic tendencies. It is likely that genetic and epigenetic factors interact to confer varying levels of resilience and vulnerability.

Gender Differences in Response to in Utero Maternal Distress

Research by Catherine Monk, Ph.D., and her team published November 26, 2019, in PNAS shows that women with clinically meaningful levels of antenatal distress are less likely to give birth to boys than women with normal distress levels. This and other research suggest that female fetuses can adapt more effectively to in utero stressors in general, including inflammation and malnutrition. Female fetuses are therefore more likely to survive. However, they may be more vulnerable to subsequent mental health challenges as a result of in utero exposure to maternal distress. Social support can influence this gender effect. Distressed pregnant women with high levels of social support are more likely to give birth to sons than distressed pregnant women with low levels of social support.

Intergenerational Transmission of Adversity

Just as there are marked inequities in the intergenerational transmission of wealth, there can be marked inequities in the intergenerational transmission of health. Pregnancy outcomes are influenced not only by acute stressors during the pregnancy, but by a pregnant woman’s past traumas and cumulative lifetime stress. These, in turn, are shaped by chronic environmental strains such as economic deprivation, racism, gender discrimination, and exposure to violence. The pregnancies of women who experience multiple intersectional areas of disadvantage may be especially affected.

The concept of intersectional adversity may also apply in utero. A fetus who is exposed to substantial maternal distress may also be exposed to other adverse influences, such as pollutants and poor nutrition.

An area of current study is whether intergenerational transmission of disadvantage occurs in part via epigenetic changes. In animal models, parental epigenetic changes induced by environmental stress can be passed to subsequent generations. It is not yet clear whether this happens in people. It is also possible that de novo epigenetic changes could arise in a fetus due to adverse maternal mental health effects from prior maternal traumas or ongoing disadvantage. For example, there is evidence that maternal stress reactivity is heightened by prior traumas and high cumulative stress.

There are also preliminary data suggesting that intergenerational transmission of disadvantage can happen via placental genetic changes. A study by Kelly Brunst, Ph.D., and her colleagues published in Biological Psychiatry on March 15, 2021, found that women who experienced higher levels of cumulative lifetime stress had higher levels of placental mitochondrial mutations.

Can Epigenetic Changes Be Reversed?

The notion of health-sapping changes in gene expression being passed down in perpetuity from generation to generation paints a darkly pessimistic picture. Fortunately, evidence suggests that adversity-related epigenetic changes can be reversed. For example, rats who were exposed to antenatal stress have reduced axonal density and altered behavior. Giving an enriched environment to pregnant rats and their offspring (increased social interaction, larger cages, and varied climbing objects) alleviates these adverse effects. Studies in humans suggest that people exposed to adverse in utero environments can achieve mental health but may need more support. They also may have to work harder at maintaining mental health through ongoing self-care. People who were exposed to substantial maternal distress in the womb may also have considerable resilience; after all, their mothers were survivors.

Detoxifying Stress During Pregnancy: How Can Delia’s Psychiatrist Help?

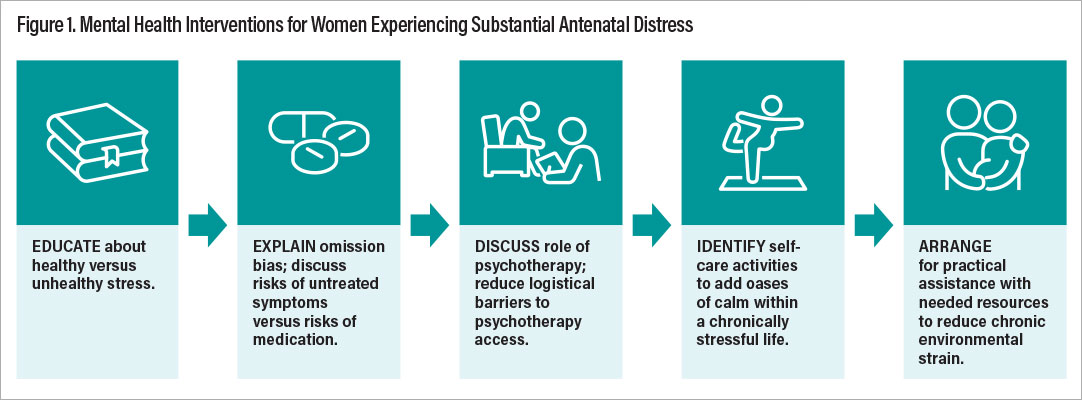

After evaluating Delia, Dr. Wilkins saw that she had a severe major depressive episode and active PTSD symptoms in the context of chronic environmental strain. Dr. Wilkins was aware that this level of antenatal distress could increase the risk of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes for both Delia and her baby. While his first impulse was to prescribe sertraline, he realized the importance of setting the stage with psychoeducation and rapport building. Here’s what he did:

•

Validated her concerns and supported her difficult decision to come see him.

•

Explained the difference between healthy and unhealthy stress in a way that clarified Delia was not to blame for harming her baby.

•

Explained omission bias, which is the tendency to worry more about the risks of things we do (for example, taking or prescribing medications) than the risks of failing to do anything (for example, leaving symptoms untreated).

•

Elicited her concerns about untreated symptoms and her concerns about medications.

•

Discussed perinatal risks of untreated symptoms versus risks of sertraline in language Delia could relate to.

•

Explained the role of psychotherapy as an alternative or additional intervention.

With these explanations, Delia decided to resume sertraline. She liked the idea of interpersonal psychotherapy but couldn’t attend in person due to lack of childcare and transportation money. Dr. Wilkins arranged for psychotherapy via telehealth.

Sertraline and psychotherapy were a great start, but given the constant strain Delia experienced, Dr. Wilkins felt they weren’t enough. He explained the concept of converting chronic stress to intermittent stress by creating “oases” of calm in an otherwise stressful life. He asked Delia how she might do that. She noted that dancing and reading graphic novels were activities she found enjoyable and relaxing and that she hadn’t done either of these since Keisha was born. Now that she saw how these activities could improve her health and that of her baby, she stopped regarding them as “wasted time.” She agreed to do these several times a week while Keisha napped. She also identified that both she and Keisha felt relaxed while coloring, so she resolved that they could do more of that together.

Dr. Wilkins also referred Delia to a social worker who helped her identify housing and financial resources, reducing some of her chronic environmental strain.

Table 1 summarizes how psychiatrists can distinguish between healthy and unhealthy stress during pregnancy. Figure 1 summarizes interventions to help women who experience unhealthy levels of distress during pregnancy.

Clinical Implications

Although much more research is needed to fully understand the impact of maternal stress and distress on pregnancy outcomes and offspring, some clinical implications are already clear:

•

Not all maternal distress is toxic. Distress doesn’t behave like a teratogen, for which any amount of exposure might be problematic. Rather, evidence to date suggests that mild to moderate, intermittent stress promotes healthy fetal development, and more severe, prolonged distress is associated with adverse outcomes.

•

It’s not entirely clear where to “draw the line” between healthy and unhealthy amounts of stress. However, one evidence-based distinction seems to be between clinically significant distress (for example, a major depressive episode, an anxiety disorder) and distress that doesn’t meet criteria for a psychiatric disorder. Another key distinction is between distress that is persistent (for example, stemming from ongoing inequities) and intermittent life stressors.

•

Just as the physical challenge of exercise is healthy during pregnancy, manageable emotional challenges are healthy during pregnancy.

•

By contrast, psychiatric disorders during pregnancy can pose substantial risks if left untreated. These risks must be weighed against the risks of psychotropic medication and/or the treatment burden of psychotherapy. Understanding this can protect against omission bias, which is the tendency for doctors to worry more about the risks of things we do (for example, prescribe) than the risks stemming from our failure to act.

•

It’s important for women to know that even in instances in which severe stress adversely affected them and/or their babies, those adverse effects can likely be alleviated by subsequent support and healthy practices.

Public Health Implications

•

Focusing on a woman’s choices and behaviors is insufficient to improve maternal mental health, pregnancy outcomes, and offspring development. Societal factors such as racism, economic deprivation, and gender inequity are strong influences.

•

An intersectional perspective explains how various social disadvantages intertwine and amplify one another to affect health in individuals and populations. The concept of intersectionality can also help make sense of the myriad interacting influences on maternal and fetal mental health during pregnancy.

•

The perinatal period is an especially opportune time to positively affect the health of women and their offspring. Public health initiatives supporting maternal mental health can be especially influential.

•

As a natural “stress test,” pregnancy can unmask physical and mental health vulnerabilities that could later become chronic illnesses. Preventive approaches during pregnancy and postpartum can help women maintain a healthier trajectory for the remainder of their lives. ■

* The case of Delia is based on a composite of several patients to ensure patient confidentiality.

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The study by Aleksandra Staneva, Ph.D., et al., “ ‘I Just Feel Like I Am Broken. I Am the Worst Pregnant Woman Ever’: A Qualitative Exploration of the ‘At Odds’ Experience of Women’s Antenatal Distress,” is posted

here.

The study by Janet DiPietro, Ph.D., “Maternal Stress in Pregnancy: Considerations for Fetal Development,” is posted

here.

The study by Kelly Brunst, Ph.D., et al., “Associations Between Maternal Lifetime Stress and Placental Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in an Urban Multiethnic Cohort,” is posted

here.

The study by Catherine Monk, Ph.D., et al., “Maternal Prenatal Stress Phenotypes Associate With Fetal Neurodevelopment and Birth Outcomes,” is posted

here.