Family interventions are effective tools to prevent relapse in patients with schizophrenia, according to a meta-analysis in The Lancet Psychiatry. What’s more, the analysis found that the simplest approach—basic family psychoeducation (classes where families are taught about schizophrenia and treatment options)—was associated with the lowest relapse rates.

This “network meta-analysis confirms the relevance of family interventions in preventing relapse in general, and the efficacy of almost all individual family intervention models,” wrote lead study author Alessandro Rodolico, M.D., a researcher in the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine at the University of Catania in Italy and colleagues. “These findings should be taken into consideration for future clinical guidelines. In particular, in the context of limited resources, family psychoeducation alone should be offered as a simple but highly effective tool.”

Rodolico and colleagues compiled data from randomized clinical trials that compared outcomes in patients with schizophrenia who had received family interventions along with regular clinical care with those receiving regular care alone. Regular care typically included psychiatric consultations; antipsychotic medication; and access to community-based services, including employment programs. Studies involving patients experiencing acute illness or concurrent medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

The final samples included 90 clinical trials with more than 10,000 patients (average duration of illness was 6.5 years) and 11 different approaches for family intervention. Most of the approaches were rooted in family psychoeducation but differed based on whether the patient was included in the family intervention and what additional elements (for example, crisis planning or skills training) were taught.

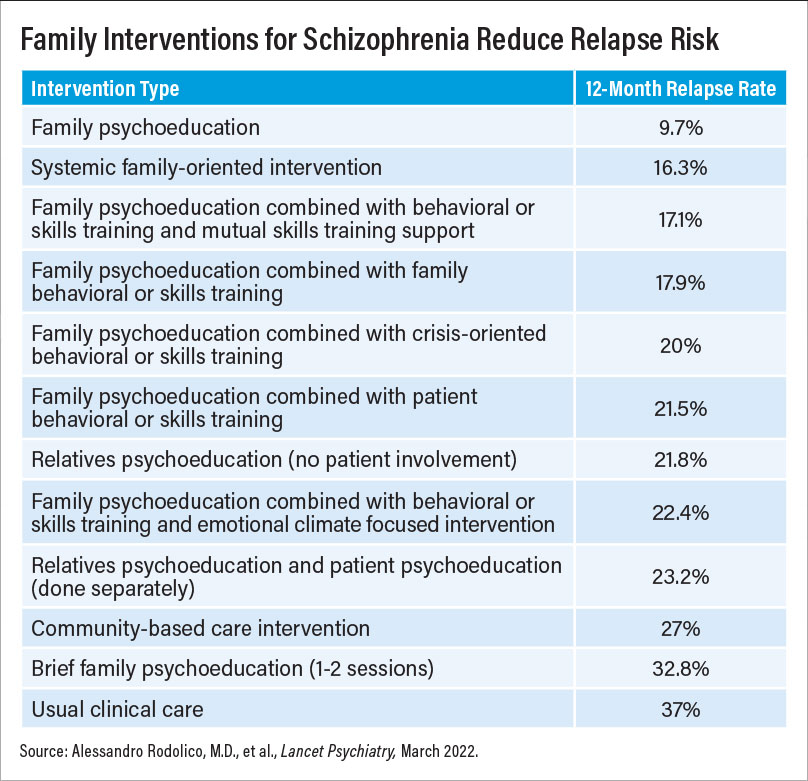

The analysis found that 9 of the 11 interventions were superior to regular care at reducing patient relapse at 12 months. Only brief family psychoeducation (just one or two sessions) and psychoeducation focused on crisis planning failed to reduce relapse in comparison with regular care. Of all the models, basic family psychoeducation that included the patient performed the best; only about 10% of patients who participated in basic family psychoeducation relapsed after 12 months compared with 37% of patients receiving regular care. The second most effective intervention was systemic-oriented family intervention, which focuses on strengthening the interpersonal relationships within a family. About 16% of patients whose families had participated in systemic-oriented family intervention had relapsed at 12 months.

“This analysis provides important and welcome news,” said Kim Mueser, Ph.D., a professor at the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Boston University who has extensive clinical and research experience with family interventions. “We’ve known for decades that educating a patient’s family about the nature of schizophrenia has a positive impact. Over time, however, the education component of a family intervention has become somewhat shortchanged,” he said.

This study suggests “there is something to be said about keeping it simple,” Mueser, who was not involved in this meta-analysis, added.

In an editorial accompanying the meta-analysis, Cherrie Ann Galletly, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Adelaide in Australia, concurred. “The meta-analysis by Rodolico … and colleagues has provided a pathway to simplify and standardize family interventions in schizophrenia,” she wrote. “The next step is to develop cost-effective educational programs, adapted for local cultures and circumstances, so that many more people with schizophrenia and their families have access to an evidence-based treatment that will reduce relapse rates.”

Lisa Dixon, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center and the director of Columbia’s Division of Behavioral Health Services and Policy Research, told Psychiatric News that the other approaches tested in this analysis should not be overlooked. “The big takeaway isn’t so much that one approach is better than the other, but that several different strategies work.”

Yet despite the many available choices, “these proven therapies are barely used,” added Dixon, who is also editor of the APA journal Psychiatric Services.

“There are many sound theories on why uptake of family interventions for schizophrenia is low, but the most practical issue is that it’s nobody’s job to make sure they’re provided,” Mueser said.

Increasing the use of family interventions for patients with schizophrenia may require dedicated staff at mental health centers to help connect families with such care, Mueser suggested. A family services coordinator, he suggested, could offer family psychoeducation, serve as a liaison with organizations that provide support to families such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and help connect a patient’s clinician and family. “We cannot overlook that one reason why these research studies showed such a beneficial effect was because the clinicians and family worked closely together,” he said. “Maintaining a close relationship with the family improves treatment monitoring, which can further reduce the risk of relapse.”

Dixon added that greater use and acceptance of family interventions is best achieved when patients are given some control over the decision-making process. “An invitation to a family intervention should start by asking patients what they think their family is doing to help them, and what theirfamily is doing that is not helpful. That conversation can help decide what approach might be suitable,” she said. “The patient should also have input as to which family [members] can attend the interventions. If [the patient] can contribute to setting the terms, the odds of engagement are greater. It doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing proposition.”

The meta-analysis was funded by a grant from the German Ministry for Education and Research. ■