During APA’s 2022 Annual Meeting, Murali Doraiswamy, M.B.B.S., sat down with Robert Califf, M.D., just a few months after Califf began his second stint as commissioner of food and drugs with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The two discussed a range of issues, focusing on potential opportunities to enhance psychiatric care and support patients.

Califf, a cardiologist by training, first served as FDA commissioner under President Barack Obama before President Joe Biden renominated him to the position in 2021. Prior to rejoining the FDA, he was head of medical strategy and senior advisor at Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google. Califf has also led major initiatives aimed at improving methods and infrastructure for clinical research, including the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI), a public-private partnership co-founded by the FDA and Duke University.

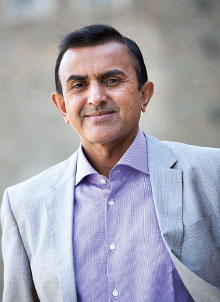

Doraiswamy is a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Duke University School of Medicine. He is also the co-chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Mental Health.

The COVID-19 pandemic is just one of the pressing health issues facing the country. Doraiswamy and Califf discussed the opioid and tobacco crises that have only worsened during the pandemic, particularly in rural America. The crises have had a “devastating impact,” Doraiswamy said.

“Addiction is a growing problem,” Califf said, noting that more than 107,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2021, an increase of nearly 15% over the previous year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He emphasized that the FDA, in collaboration with the Drug Enforcement Administration, is taking actions to address the opioid crisis. He referenced a presentation he made at the 2022 Rx and Illicit Drug Summit in Atlanta in April where he listed some of those actions the FDA is taking, including supporting the development of nonaddictive pain treatments and working to ensure the availability of medications to treat opioid use disorder.

A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it allowed remote care, particularly telepsychiatry, to become much more widespread, Doraiswamy said. Yet many have also turned to digital tools, such as mental health apps. “There are tens of thousands of mental health apps out there, [and] it’s really hard for a consumer to tell which is a good app, which is a bad app,” he said.

Califf has been immersed in the world of digital health, particularly while working at two of Alphabet’s subsidiaries, Google Health and Verily Life Sciences. “To start with, we need to step back and acknowledge that digitization in our society and broad access to the internet are having profound effects that we don’t yet understand,” he said. “I personally believe the assumption that these technologies don’t have specific risks is an incorrect assumption. And just like any intervention, the net benefits outweigh the net risks, or they don’t, and that determination ultimately will need to be made.”

The FDA is adaptative in its approach to the regulation of digital health tools, he continued. It is looking at a digital product’s total life cycle, emphasizing that algorithms must be continuously assessed, much like the way postmarketing surveillance is conducted with drugs and devices.

Doraiswamy and Califf also discussed evidence generation and how the FDA is working to improve the quality of available evidence to inform care.

“Our research system is way too expensive, way too cumbersome,” he said. “It takes too long. It often doesn’t address the questions that really matter to patients and clinicians who care for them. … We also have to have systems that identify the important questions and make sure we work together to answer them.”

There are too many small studies being conducted in academic medical centers by people trying to get tenure or fellows that do not answer really meaningful questions, he said. Those trials absorb the resources that otherwise could go to large studies that really matter.

The psychiatric field has been especially impacted by low-quality studies, he continued. “Clinicians in the U.S. are under tremendous duress, and your field is probably number one. There’s just not enough of you, and you’re under constant pressure and financial stress. … We’ve got to come up with a way to get the evidence we need.”

Finally, Califf and Doraiswamy discussed diversity and inclusion within clinical trials. Califf stated bluntly: “We have a lot of work to do.” If inclusion were represented in terms of a curriculum, he continued, the United States would be enrolled in Inclusiveness 101.

Reaching level 201 requires not just inclusion in clinical trials on the basis of race, ethnicity, or sex, but also on a number of other characteristics, including gender, socioeconomic status, and educational attainment. Ultimately, the highest level of inclusiveness would take into consideration that this country represents only 4% of the world’s population. “What would the size of clinical trials need to be [in order] to be inclusive of over 250 ethnicities in the world?” he said.

Such broad inclusivity is exciting, he added, thanks to technology that allows data sharing. “There’s no reason that, globally, we couldn’t develop medical products and concepts of clinical care and share those data if we work out the rules by which to do it,” he said.

The FDA is currently hiring and looking ahead at global collaboration. “We’re all dependent on each other,” he said. “If we didn’t believe that before, the pandemic has made that abundantly clear.” ■