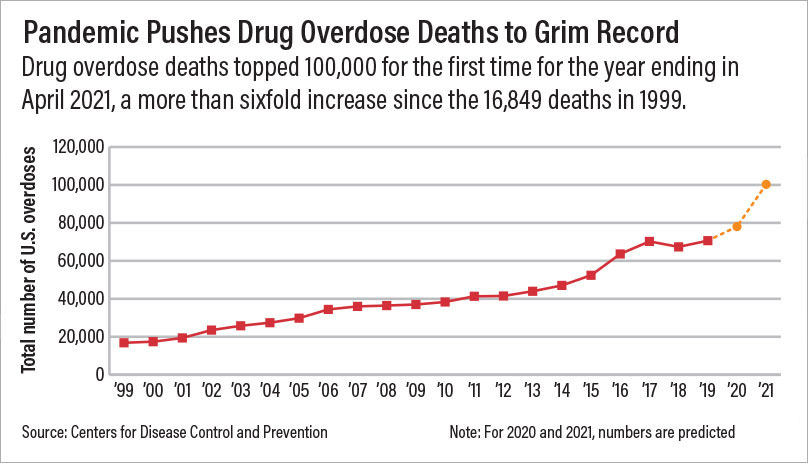

Drug overdoses killed more than 100,000 people in the United States during the one-year period ending April 2021, marking the first time that overdoses reached six digits in a span of 12 months, according to provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The grim milestone represents a 29% increase in overdose deaths from the prior year.

Synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl and its analogs, were responsible for 64% of the total deaths for the one-year period, a rise of nearly 50%, according to the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. Psychostimulants with abuse potential such as methamphetamine were responsible for 28% of the total deaths, a 48% increase from the previous year.

In response to the CDC data, APA released a statement renewing its call for improved access to mental health and substance use services through early identification, utilizing evidence-based models that integrate behavioral health treatment into primary care services. APA also called for policies and programs to provide effective substance use disorder (SUD) treatment for all patients, to support medical schools and residency programs in training clinicians to treat people with SUD, and to encourage the development of an addiction workforce.

“As a country, we still have a lot to improve on when it comes to following the basic tenets of SUD care,” Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D., clinical director of the Division of Alcohol, Drugs, and Addiction at McLean Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, told Psychiatric News. “We were not providing sufficient quality access to SUD services when heroin was the main illicit opioid, and now that fentanyl has largely replaced it, it is even more challenging because fentanyl is more deadly and more difficult to reverse with naloxone. It is also more difficult to stabilize a fentanyl-addicted person with medication-assisted treatment than it had been with heroin.”

She continued, “We know the public health basics needed to adequately address the national opioid use disorder and drug overdose crisis, but we have been slow to implement these, and during this delay, drug traffickers are finding ‘improved’ ways to profit and to avoid detection and legal consequences.”

The health care community, policymakers, and the public need to address SUDs and substance use in a way that reduces stigma and isolation, Smita Das, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., chair of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry, told Psychiatric News. Das is an addiction psychiatrist at the Dual Diagnosis Clinic and a clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, both at Stanford University. “As we break down those larger barriers, it is important to recognize that a piecemeal or fragmented approach is not enough. While I applaud the incremental policy changes that are occurring at multiple levels, the problem is like a bucket with many holes—we must patch multiple holes at a time to make a true difference.”

Call to Psychiatrists

Das pointed out that more than half of individuals with SUD have a comorbid mental illness, and overdoses may involve substances besides opioids, such as alcohol and polysubstance use. “Substance use and SUDs are part of what psychiatrists need to address in practice, advocacy, and education. … Psychiatrists can absolutely impact this crisis.”

“By asking all patients about substance use nonjudgmentally and systematically, psychiatrists not only identify [individuals] needing treatment, but we can further reduce stigma by letting our patients know that we are interested in the bigger picture of their mental health, which may include substance use. Psychiatrists are inherently skilled at integrating motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral treatment, which is the gold standard in psychotherapy for SUD.”

Connery called on psychiatrists to include treatment of SUD in their practices and to become familiar with prescribing of the three FDA-approved medications to treat opioid use disorder (buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone) as well as naloxone rescue. “Psychiatrists are in an excellent position to address the mental health challenges faced by patients with SUD, including work targeted to reduce the elevated risk for premature mortality in these populations, such as prevention of overdose, drug-related motor vehicle accidents, domestic violence, and suicide,” she said.

Last November, the White House Office of Drug Control Policy issued a model law states may adopt to expand access to naloxone. At present, naloxone access is largely dependent on where one lives, according to Rahul Gupta, M.D., director of National Drug Control Policy. The model law aims to be a template for state legislatures and would require health insurers to cover naloxone, encourage citizens to obtain it, protect individuals from unjust prosecution for administering it, and increase access in educational and correctional settings.

Also in November, the Department of Health and Human Services released an overview of the Biden administration’s plan to combat drug overdoses. It includes measures designed to remove barriers to prescribing medication for opioid use disorder; reduce stigma; and provide new funding for prevention, evidence-based treatment and recovery support, and harm reduction. ■

APA’s statement on the CDC report on overdose deaths is posted

here.

The CDC data are posted

here.