It is common practice in medicine to measure patients’ treatment response across the disease spectrum ranging from biometrics (vital signs, blood pressure) to imaging studies (X-rays). Patients’ self-report of symptoms are typically also captured in conjunction with quantifiable measures, facilitating an integration between the qualitative and quantitative in patient-centered care. Although an expected part of practice in general medicine, quantifying progress in mental health has been largely overlooked. The reasons for the slow adoption of gauging psychiatric progress may be a topic for spirited dinner conversation, but some of the likely culprits are long-held biases against relying on psychometric scales, concerns about unreliable patient self-reports, and/or practitioner reluctance to augment their clinical judgment with data (the reader is encouraged to read the article “Clinical Versus Actuarial Judgment” noted in the Suggested Reading list at the end of this article). But the fact that mental illnesses are among the most common health conditions in the United States, and anywhere from 32% to 67% of patients drop out of psychotherapy before benefit is realized, has prompted national organizations to implement a system of measurement-based care (MBC) into their practices. In fact, if you are part of an accredited practice, The Joint Commission and Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) require it. If you are on insurance panels, third-party payers may request it; moreover, it is now common for pay-for-value managed care reimbursement rates to include quantifiable therapeutic outcomes.

Despite CARF’s having required its facilities to implement programs of outcomes management to assess patients, track progress, and report outcomes since 1998, much of the recent momentum toward implementing measurement-based care into psychiatric treatment and psychotherapy is largely due to the powerful policy brief published by The Kennedy Forum in 2015. This report outlined the importance of adding psychometric scales to enhance treatment decision-making and treatment plan alterations to achieve a deeper therapeutic alliance and to prevent treatment failure. The Joint Commission soon followed thereafter by publishing in January 2018 the revision to its Outcome Measures Standard CTS 03.01.09, which requires mental health–accredited facilities to implement the use of valid psychometric scales. The revisions directive is not only to gauge treatment progress, but also to demonstrate that treatment plans are modified based, in part, upon reviewing patient responses from those psychometric scales.

The evolution of psychotherapeutic care to incorporate measurement-based care is clearly much more than tossing in a smattering of valid psychometric scales. The term “measurement-based care” embodies the essence of its aim as a shift in routine therapeutic practice: to utilize and incorporate psychometrically sound symptom scales as tools to enhance the understanding of mental health issues and to support the clinical process. Typical of the taxonomic process in our field, several iterations designating measurement-based care have been proposed throughout the last two decades, such as Routine Outcomes Monitoring, Progress Monitoring, and Concurrent Recovery Monitoring. The overlapping fundamentals among all these models is that some form of quantifiable evaluation of psychiatric symptoms be collected and used to inform treatment; the disparities among them appear to exist primarily in the nuanced methodology of monitoring therapeutic progress.

Why Do Measurement-Based Care?

Clinical psychologists have long known that psychometric evaluation augments clinical practice by clarifying symptom presentation, differentiating diagnoses, and deepening understanding of the clinical profile. This process in turn serves as the baseline assessment from which subsequent measurement data can be compared to assess therapeutic change. The results of these measures should not, however, remain concealed in the patient file; when the findings of psychometric data are discussed with patients along with clinical impressions, it allows for deeper understanding and often validation of the patients’ psychological struggles. If therapists can continue to administer the same measures at designated times during treatment, it will help gauge treatment and facilitate conversation about progress as part of the therapeutic hour.

In fact, several well-designed studies have demonstrated that measurement-based care used in this manner may enhance therapeutic alliance, improve therapeutic compliance, foster insight, and prevent treatment failure. Michael Lambert refers to the latter function of measurement-based care as a “signal alarm system.” Measurement-based care essentially helps the clinician become aware of negative change or clinical inertia. Changes to treatment can then be addressed and proceeded. This function is fundamental to The Joint Commission’s 2018 mandate for implementation of measurement-based care. The mandate to Standard CTS 03.01.09 is based on the compelling, consistent outcomes of this body of research, which demonstrates that measurement-based care does, in fact, catch patients before or as they fall through the proverbial cracks.

Implementing Measurement-Based Care

Although measurement-based care serves to substantiate the clinical process through quantifying progress, at its foundation, it is a data collection method, similar in design to treatment-outcomes studies published in peer-reviewed practice research, that requires the use of standardized procedures. Adopting these data collection methods serves as an excellent template for the implementation of measurement-based care. The good news is that the standard operating procedures of most clinical practices parallel those of treatment-outcomes studies.

Treatment-outcome study design incorporates two important features relevant to clinical practice: Establishing a baseline and the use of repeated measures.

•

Collecting data at pretreatment or prospectively is essential; the data serve not only as a baseline or starting point from which to compare patient progress, but also represent as close to a scientific “control” as possible in the naturalistic world of psychotherapy. Clinicians cannot control for all factors associated with the life history of patients prior to treatment, but collecting intake status allows measurement-based care to potentially quantify the extent of therapeutic change and outcomes. Therefore, it is critical to capture patients’ status before the first therapeutic encounter and to note the date.

•

The second important feature of measurement-based care is its “repeated measures” method. Identifying the time intervals at which measuring treatment progress is collected and maintained should be dictated by the structure and needs of the clinical practice. The key to keeping the lid on data collection from overspilling into an unstructured, overwhelming miasma is to establish a coherent infrastructure prior to launching measurement-based care.

It is important that measurement-based care synergizes with the clinical practice; therefore, a few additional points should be considered prior to implementation. It is important that clinicians clarify their clinical practice vision, as well as identify pertinent stakeholders with whom they will share patient information. This thoughtful exercise will provide the context from which to choose your measures and thus guide the interpretation of therapeutic progress and outcomes. This is one of the most important functions of how therapeutic monitoring augments the clinical process: The clinician—as the interpreter of the data—interprets changes in psychiatric symptomology outcomes within the context of where the psychotherapeutic effect took place. Without synergizing measurement-based care into the practice vision will limit its utility to signify mechanisms of change.

Selecting measures should be essentially one of the last tasks after determining practice vision and need. The process can range from patient- to practice-centered approaches. The most tailored approach is to administer symptom-rating scales specific to the presenting problem and unique to each patient; this method entails acquiring not only a library of varied psychiatric symptom scales, but also a certain degree of psychometric assessment acumen. A less patient-centric approach, but one more practice-oriented, is to employ a standard scale or battery of scales to measure all patients irrespective of presenting problems. If done thoughtfully and thoroughly, this approach not only facilitates meaningful, individualized measurement-based care, but can ultimately—over the course of one’s practice—be aggregated to measure program fidelity at the systemic level. For larger clinics or behavioral health care organizations, measurement-based care data, when collected in a systematic fashion, can be incorporated as part of one’s quality assurance system in keeping with Donabedian principles to gauge overall treatment effectiveness and quality of care.

It should not be a leap of faith to ascertain the potential for aggregated therapeutic progress data to be an invaluable tool to assess program fidelity. All clinicians, whether in private practice, group practice, or larger treatment facilities, are ethically obligated to ensure using best practices. What better way to determine the effectiveness of treatment or clinical programming than through collecting and analyzing systematic data across patient populations and over time? Testimonials often warm our hearts, and many institutions publish these on their practice brochures and websites, but to truly substantiate outcomes and elevate psychiatric treatment to practice-based evidence levels, those testimonials should be backed up with honest, clean, aggregated data.

Clinically Applying Measurement-Based Care

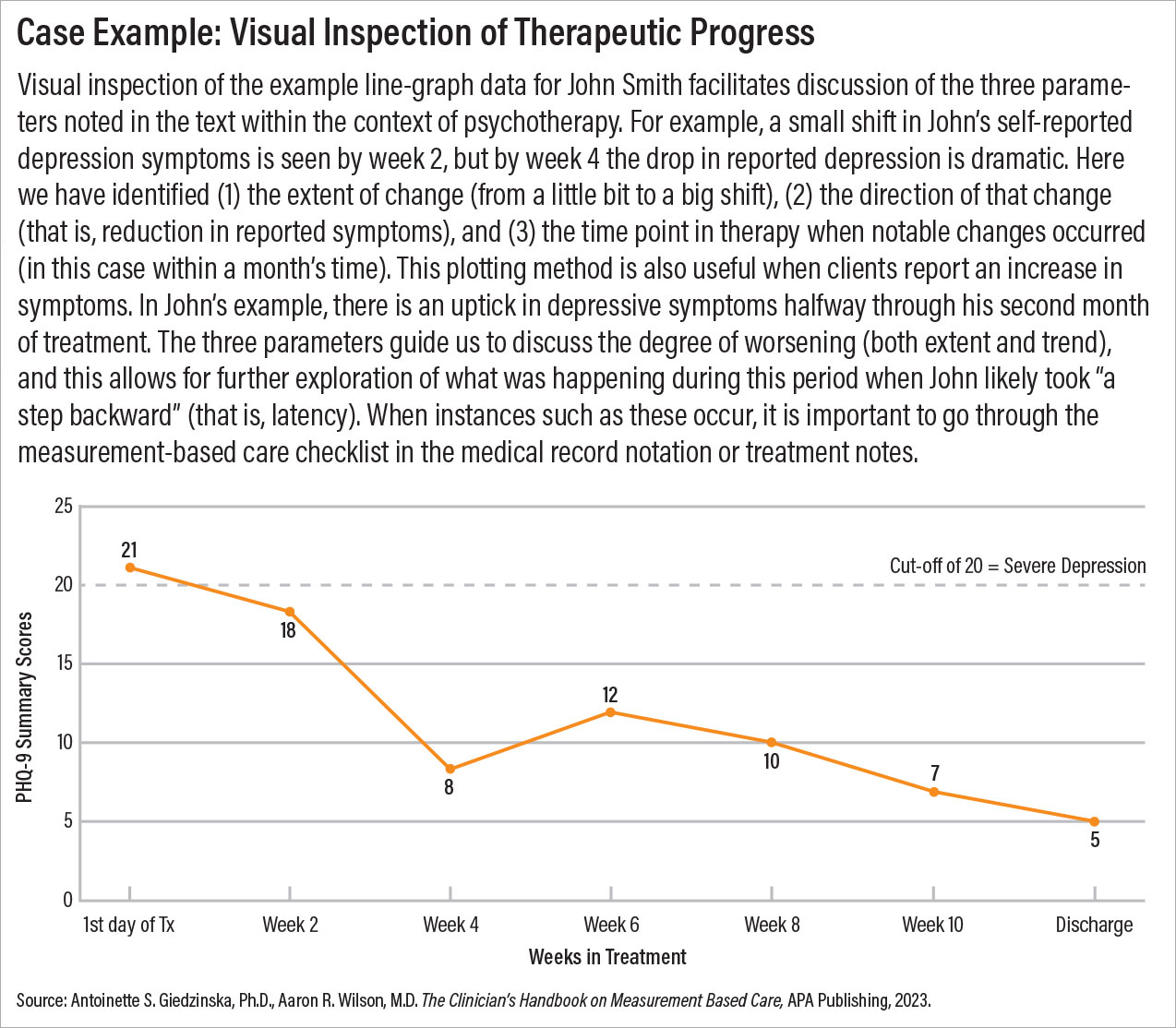

Employing data from measurement-based care should not be an insurmountable task, nor should it require advanced statistical prowess. Choosing psychiatric symptom screeners with simple scoring rules (preferably summary scores) and plotting those scores onto graphs is one of the easiest ways to track patient progress and visually inspect those trends with patients as part of the therapeutic encounter. In general, most of us have navigated the educational system and are thus familiar with the concept of a report card. Therefore, plotting scores on a line graph over time starting with pretreatment status is an efficient and effective way to employ measurement-based care. Line graphs, when clearly denoted, are easy to follow and monitor trends in progress.

When visually inspecting data, clinicians should follow three parameters: the extent of change between data points (that is, how big?); the direction of that change or how progress is trending (for example, is my patient getting better or worse?); and latency (such as identifying how long it took to observe a change in scores). Each one of these parameters can be discussed with patients if warranted and used therapeutically to explore their responses. An example of this process using PHQ-9 data is illustrated in the case example above.

•

Did you identify and thus discuss the increase in symptom reporting?

•

Did you address changes to the treatment plan?

•

Did you note in the medical record which treatment modifications were made?

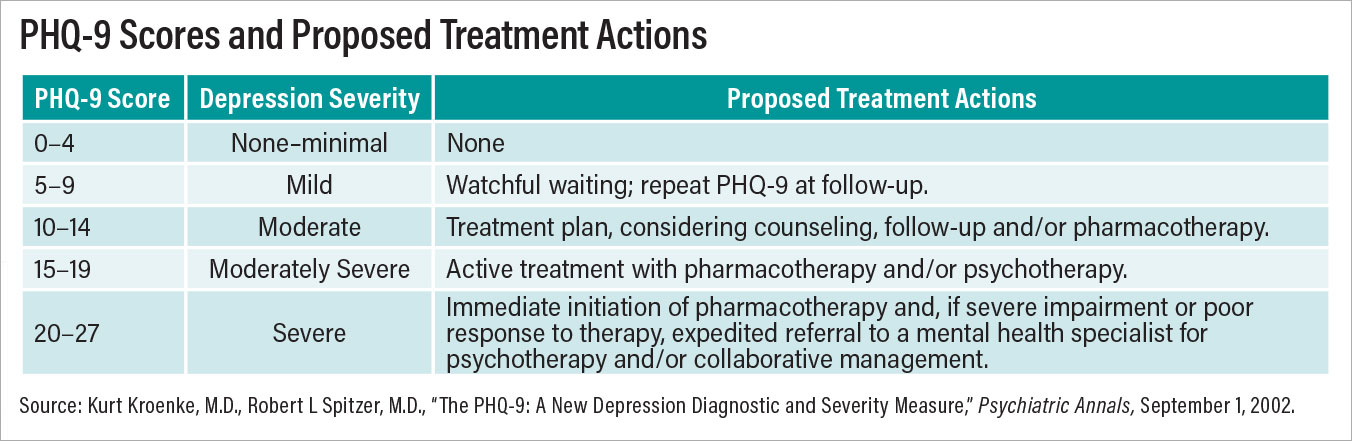

Lastly, there are a few additional considerations one should keep in mind when visually inspecting data. It is important at the outset to take the time to explain to patients what the scores on the graphs actually mean. Most psychiatric symptom screeners provide scoring rules and interpretive guidelines. Others—for instance, the PHQ-9—also provide “treatment actions” (for those inclined to use them) based on scoring outcomes (see table).

Another consideration is to brush up on hypothesis testing. Although comparing two data points through visual inspection does not require parametric statistics, one should use caution when interpreting or signifying “change.” Type I errors (that is, failing to reject the null hypothesis or, in clinical practice, assuming true change has occurred when it hasn’t) are slippery fellows. Therefore, it is advisable to express measurement-based care data output more often as “indicators” or “trends” during clinical encounters.

Lastly, and in some instances most importantly, discussing trends in the summary score itself should suffice when reviewing patient progress. Nevertheless, there may be occurrences when discussing specific items of a scale are justified; namely, those items specific to clinical relevance or severity (that is, change in a test answer on suicidal ideation). If a screener includes critical alert items, clinicians should pay close attention to those responses every time the screener is scored.

Defining the Practice of Measurement-Based Care

We view measurement-based care as a substantive clinical tool with multifaceted applications. In summary, measurement-based care is the systematic collection of individual data acquired at initial screening, at various identified times during treatment, and at completion of care. Its primary function is to substantiate diagnostic formulation, guide treatment decisions, monitor treatment progress, and evaluate treatment outcome at the individual level. Its secondary function is to evaluate programmatic fidelity in aggregate form as a method of quality assurance to evaluate treatment effectiveness, analyze outcomes, understand predictors of patient progress, and determine factors toward treatment improvement.

Summary and Implications

In the current milieu of managed care, in-depth and lengthy conversations that align with patient-centered medicine to assess patient preferences, needs, and values may pose as a logistical nightmare in some practices. Therefore, the inclusion of measurement-based care may serve several additional functions to enhance the patient-centered care practice. The first function is about personalization. The well-chosen instrument(s) can summarize presenting problems, important beliefs and values, and social determinants necessary for well-rounded conceptualization. The data gleaned from this process can yield important, unique client information that will further tailor treatment planning to meet the distinct needs and desires of patients. To some degree, measurement-based care embodies “personalized medicine” such that the information gathered through clinical assessment is used to tailor treatment.

The second and third functions are about time efficiency and its impact on doctor-patient communication. The time taken to complete the administration of psychometric evaluations will be markedly less than gleaning such information in a traditional clinical interview. Consequently, more time is made available to actually do therapy and clinical work and establish rapport and therapeutic alliance, and less time involved in perfunctory “interviewing.” Having more one-on-one time with patients further supports the quality of patient-centered care. With each review of therapeutic progress via measurement-based care, clinicians are appraising and reappraising their treatment approach and plan. Personalized treatment through measurement-based care thus becomes a dynamic and engaging process.

Metaphorically speaking, measurement-based care may be the pepper to the salt of psychotherapy. When used clinically, data from measures do more than merely “quantify” therapeutic progress; good data help to tell the story of therapeutic healing. Although data are inherently scientific, the tangibility of presenting and discussing data with patients can be truly magical when it promotes the noteworthy “ah HA!” moment of psychological insight or therapeutic hope. When integrated into the clinical process, measurement-based care can provide a fortification to one’s overall practice and clinical programming. ■